I don’t understand how the Parisians let Leslie Caron slip through their hands. In 2013, she sold her apartment overlooking the Musée d’Orsay and moved to London in order to be closer to her children (by the late theater director Sir Peter Hall) and grandchildren. She now lives in some style a short walk, with her dog, Jack (named after the actor Jack Larson), from Kensington Palace.

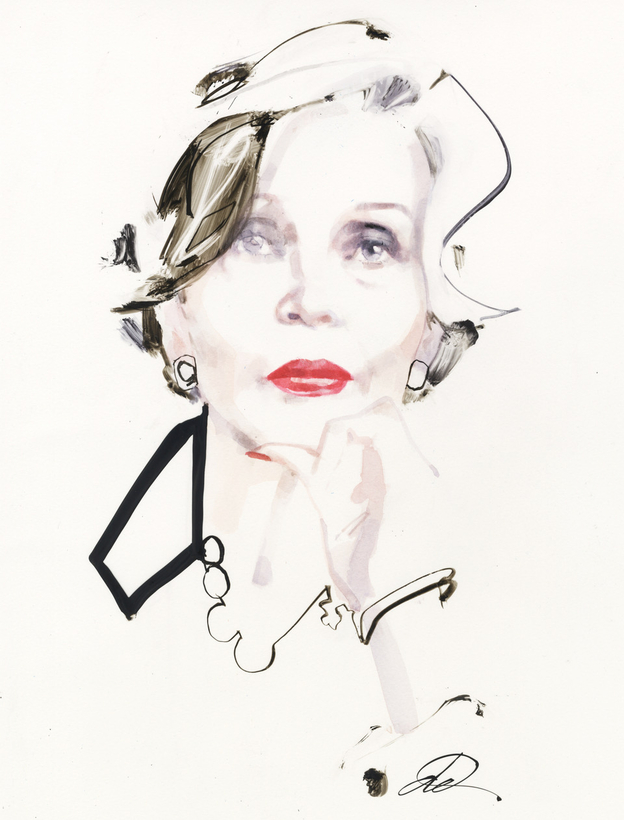

Paris’s loss is London’s gain. I met Leslie several years ago at a sausage-and-mash supper hosted by Nicky Haslam. I asked her if she would consider sitting for a drawing. She thought about it and called me a few weeks later. The portrait worked out well, and we became fast friends, meeting for regular one o’clock lunches at the Wolseley on Piccadilly. (Although I quickly discovered that, unlike many stars of Hollywood’s golden age, Leslie is early for everything—she puts it down to her MGM training. I learned to arrive promptly at 12:45.)