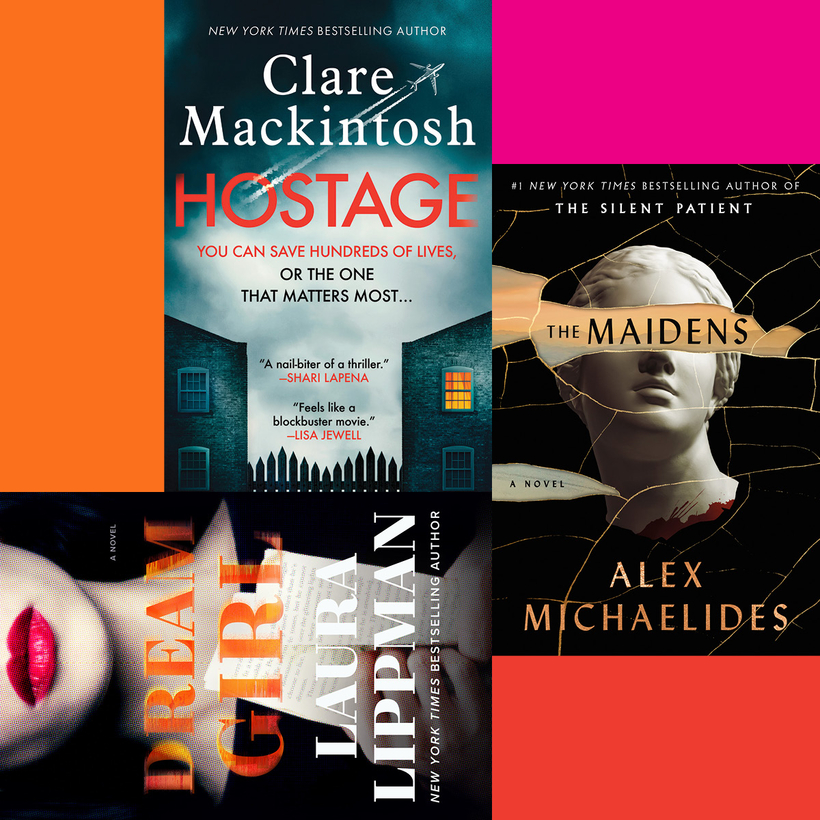

Hostage by Clare Mackintosh

As if rowdy passengers and coronavirus jitters weren’t bad enough, Hostage reminds us, in the scariest possible way, that worse things can happen on an airplane.

It begins routinely enough, with flight attendant Mina Holbrook switching schedules with a colleague in order to work the inaugural nonstop London-to-Sydney route for World Airways. Her home life is a bit stressful, and she needs a break. Midway through the flight, she receives a heart-stopping note: either she gives as-yet-unidentified hijackers access to the pilot’s cabin or accomplices back home will harm her daughter. In the hours remaining, Mina has to reconcile her desire to save her child with her responsibility to the 353 passengers onboard.