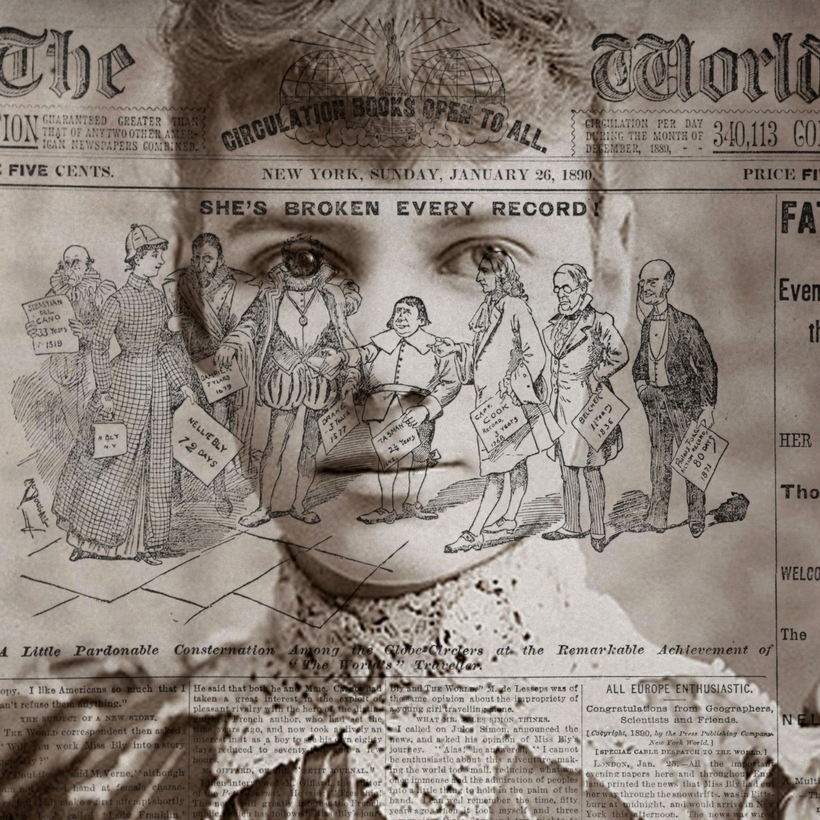

Long before Gloria Steinem put on rabbit ears and a drum-tight satin corset to chronicle life as a Playboy bunny in a two-part series for Show magazine in 1963; before journalist Barbara Ehrenreich worked a slate of menial jobs to see if she could live on a minimum wage, heavy lifting that formed the basis of her 2001 book, Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America; before Torchy Blane and Lois Lane and Brenda Starr, there was doughty Nellie Bly feigning madness to expose the horrors at a New York City insane asylum. Bly, Elizabeth Banks, Eva Gay, Eliza Putnam Heaton, Elizabeth Jordan, Victoria Earle Matthews, Nell Nelson, Winifred Sweet, and Ida B. Wells are among the journalists who populate Kim Todd’s Sensational: The Hidden History of America’s “Girl Stunt Reporters.”

In the late 19th century, opportunity knocked for ambitious female journalists who had no interest in the society beat. The publishers of big-city dailies, such as Joseph Pulitzer at the New York World and William Randolph Hearst at the New York Journal, were looking to beef up circulation and to best the competition; meanwhile, the influx of immigrants into the U.S. promised a whole new audience.