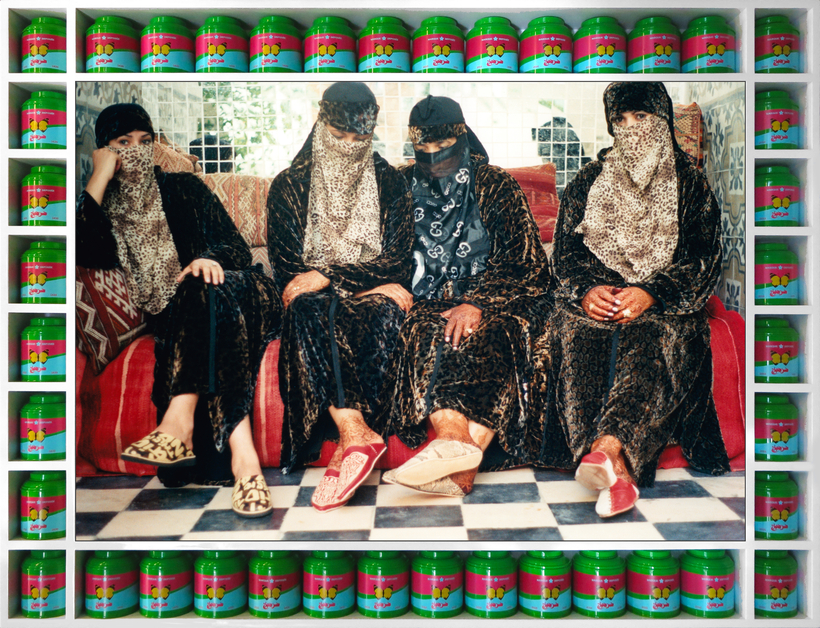

Vogue: The Arab Issue is the title of a photographic series created by Hassan Hajjaj in the 1990s. It’s also the title for Hajjaj’s latest exhibition, which includes the original series and four others, now on at Fotografiska, in New York City. A nod to Vogue’s fabled fall blockbuster, commonly referred to as “the September Issue,” the exhibition playfully puts the stress on the word “issue.” Hajjaj is pointing up a trope that has been a piece of the Vogue paradigm since the 1960s: the fashion shoot that is part fantasy travelogue, part cultural appropriation.

You know what we’re talking about: models in Paris couture posed among indigenous peoples in native dress. Diana Vreeland, editor of Vogue from 1963 to 1971, possessed a no-boundaries, pan-national aesthetic when it came to beauty. She wasn’t P.C., not the tiniest bit, and yet her pages were vibrantly multicultural decades before the word went mainstream. Vogue after Vreeland was not as worldly. It continued to trot out the travel trope, but with far less love. (In fact, the fashion pasha André Leon Talley recently called Anna Wintour, Vogue’s editor since 1988, a “colonial dame.”)