Book writers’ partners play a variety of roles. Some are involved not at all until the book is birthed, and others are involved every inch of the way through the research, interviews, and editing. My role with Walter (to whom I’ve been married for 35 years) is a bit more like a two-sided funnel.

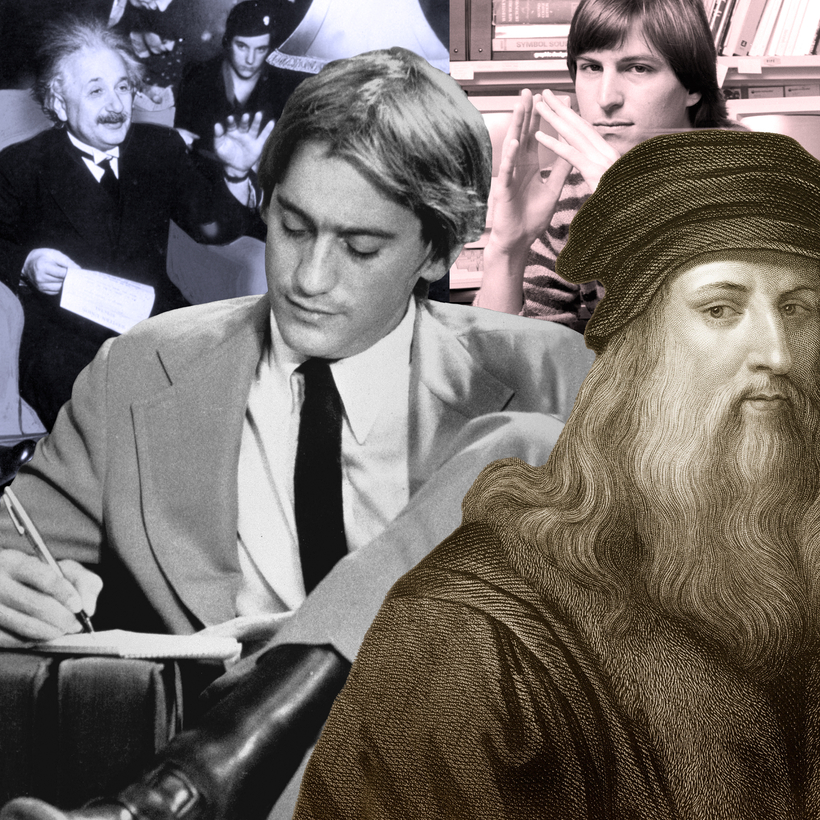

In the beginning, the funnel is wide. There’s the anticipation. We have wonderful discussions about why the book is interesting to us, why it’s important, and why others might like it and learn from it, too. And there’s the research, where we travel to fabulous museums (Leonardo), historic cities (Ben Franklin), transformative subcultures such as Palo Alto (Steve Jobs), and universities like Princeton (Einstein), where we puzzle out science or art or the nature of curiosity. Life is sunny.