It is not easy being the child of a great or famous person. Endless celebrities’ children’s memoirs remind us of that doleful fact, to the point that Famous-Parent Syndrome ought to be a recognized psychological illness. One person who coped with it well was Sir Winston Churchill, but then his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, died aged 45, when Churchill was 20 years old, and so could not stymie his son’s life.

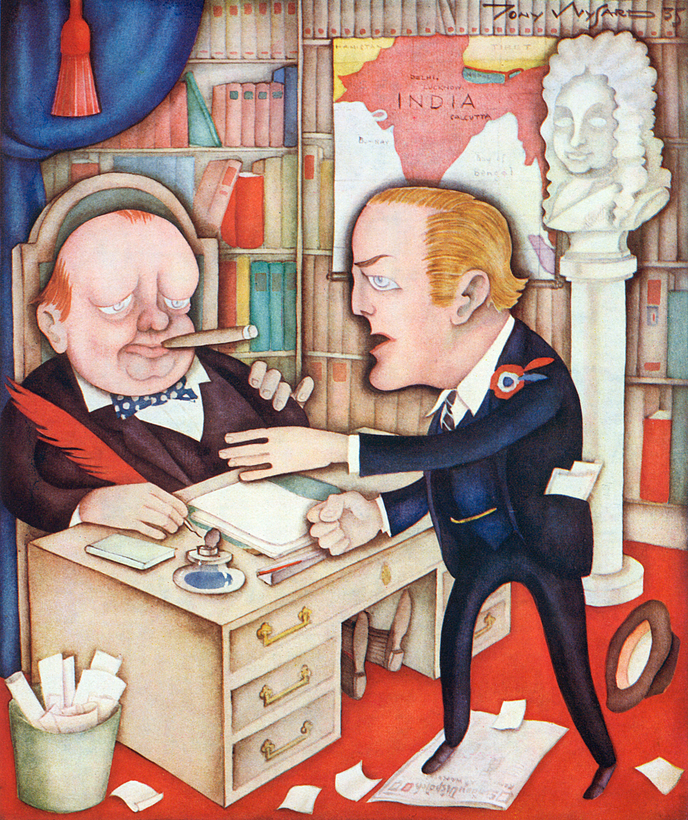

By contrast, Winston himself lived to be 90, and it is the contention of this well-researched, well-written, but often misguided book that he utterly stymied the life of his own son, whom he had named Randolph in fealty to his dead father. “Winston demanded an asphyxiating loyalty from those closest to him,” argues the author of this book, Josh Ireland. “This meant that Randolph was compelled to attach himself to a series of doomed, unpopular causes.… Every step Randolph took to try to set a course of his own was treated as if it were a deliberate attempt to sabotage his father. The inhibiting effect of his fidelity prevented him from ever building an identity, or a career that was truly his own. At the same time he was desperately trying to live up to the prodigious ambitions that Winston had implanted within him.... Randolph was trapped in a cage built by his father.”