In another lifetime not very long ago, I spent an autumn sitting on the grass of the Great Lawn with my friend Zach, both of us unemployed but cigarette-rich. We’d become acquainted with a life of quasi-bucolic unrest—poverty in the park—and taken up the hard-pressed refrain “What are we going to do?” as though the answer mattered to anyone other than us. Zach, misguided in the way that only a child of New York can be, longed to work “in sports.” (He’s now gainfully employed at one of the finest hotels in the city, don’t worry.) I, dim-witted and obtuse as only someone from the backwoods of Connecticut can be, wanted to work in the flourishing world of print magazines. (Have pity, I got my wish.)

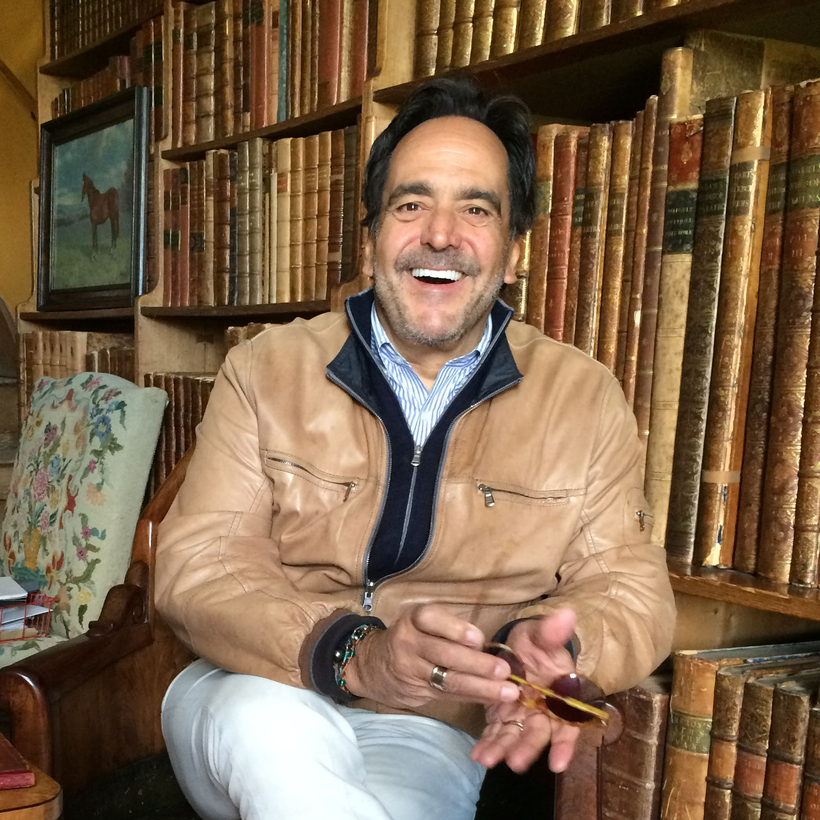

One afternoon, lying in the field with our bovine faces turned skyward, Zach muttered to me, “You know … you could meet with my dad. He’s an editor and might have some advice.” Zach left no room for hope of employment, but it was a start. His father, Richard David Story, had for a decade and a half presided over a travel magazine called Departures, and was just the sort of person I’d been cold-emailing for months, seeking a job, a meeting … hell, the mere courtesy of a rejection.