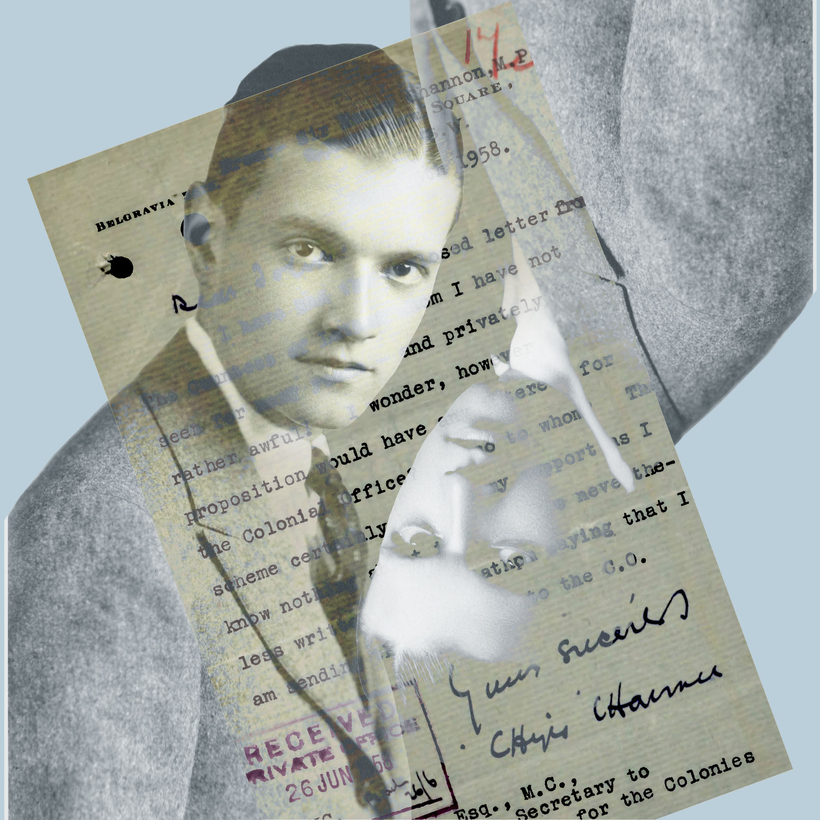

Contemporaries of Henry “Chips” Channon’s would be astounded that he is generating headlines more than 60 years after his death. The son of a rich Chicago businessman, Channon moved to London shortly after the end of the First World War, where he became an indefatigable socialite, entranced by the British aristocracy. Having become a British subject in 1933, he entered Parliament two years later, but, despite a 23-year political career, rose no higher than a brief spell as parliamentary aide to a junior minister. Then, in 1967, nine years after his death, came the publication of his diaries.

Frivolous, gossipy, and waspish, the diaries were a literary sensation. The foibles and trivialities of recent high and political society were laid bare, and even Channon’s natural enemies could not help but be impressed. “What sharp an eye! What neat malice!” extolled one reviewer, despite blasting the author for his snobbery.