There’s a certain kind of book that defies a direct approach. It arrives on the doorstep, several inches thick, dense with learning. With a winch you hoist it to a table, where it intimidates the books already there. Occasionally you sidle up to it, as if it were the Maginot Line, then opt for a flanking maneuver. If the pandemic were to last another decade, there could come a point when you might be tempted to consider cracking its spine, only to retreat to the comfort of The Anatomy of Melancholy or A Brief History of Time.

And that would be a mistake, at least if the book were Ritchie Robertson’s thousand-page The Enlightenment, a beautifully written account of a period that everyone has heard of but few pause to think about.

Once, on a high-school paper, I tried to speed up the pokey narrative with a singular feat of concision: “Then along came the Enlightenment.” Robertson, a professor at Oxford, has helpfully filled in what I left out. He defines the Enlightenment—a term more recent than the thing itself—as a period unfolding over little more than a century when, in a remarkable burst, thinkers and writers sought to remove the scales of “false beliefs”; undermine the power of oppressive institutions; come to a better understanding of human nature; and, through empirical discovery, make pragmatic improvements in ordinary life—all with a view to increasing “people’s well-being and happiness,” the ultimate goal.

Busting Myths

Robertson is determined to reclaim the Enlightenment from enemies and misconceptions. It’s easy, he writes, to blame the French Revolution on the Enlightenment, with eager philosophes plotting the regime’s overthrow—“easy, but wrong,” he explains. In the Enlightenment’s embrace of reason and science, some have discerned the origins of technocracy, totalitarianism, and a zest for the domination of nature. People of faith have argued that the Enlightenment’s elevation of human capability comes at the expense of the divine. Racism, sexism, and a belching, destructive capitalism have all been laid at the Enlightenment’s feet. Not to mention an overweening individualism. And a farcical utopianism. And a desire for colonial mastery.

The historian Eric Hobsbawm, affirming his own Enlightenment values in a famous lecture 30 years ago, acknowledged that the Age of Reason had come to be viewed by many as “a conspiracy of dead white men in periwigs to provide the intellectual foundations of Western imperialism.”

The indictment is contradictory, and endless. Robertson is not uncritical, but he takes issue with, or qualifies, these and other charges leveled at those he calls “Enlighteners,” a catchall term that includes everyone from the grand thinkers—Voltaire, Rousseau, Newton, Hume—to agrarian reformers and village autodidacts. (The Enlightenment seeped everywhere—one of Robertson’s points.)

It’s easy to blame the French Revolution on the Enlightenment, with eager philosophes plotting the regime’s overthrow—“easy, but wrong.”

Enlighteners may have railed against superstition, and against religion when it departed from reason, but they were not opposed to religion itself, and most of them were at least Deists: “Only a small minority thought there was no God, and they took care not to advertise their skepticism.”

The Enlighteners embraced science, mathematics, and technology, but they did not see human beings mechanistically—merely as “data”—or conceive the ideal human future as one of regimented cyborgs. Anticipating the Romantics, they fostered “a sea change in sensibility, in which people became more attuned to other people’s feelings and more concerned for what we would call humane or humanitarian values.”

Enlighteners may have railed against superstition, and against religion when it departed from reason, but they were not opposed to religion itself.

Although a caricature has taken hold—those exalted men in periwigs—the Enlighteners were as apt to be municipal functionaries or pragmatic merchants as they were to be powdered intellectuals in the salons of Paris. And it wasn’t just Paris anyway: the Enlightenment was a “diverse but single phenomenon” that took root in many places, “from Philadelphia to St. Petersburg.”

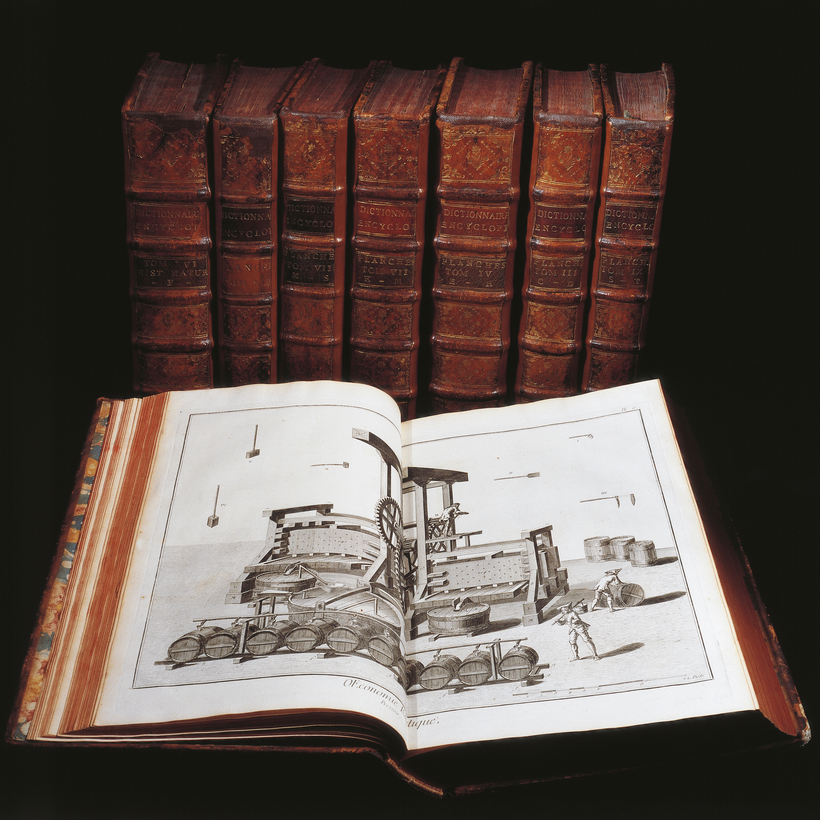

The Enlightenment is not dry. Robertson takes us to Russia: In 1698, a modernizing Peter the Great, impressed by current fashions in an enlightening West, condemns the beards of aristocratic aides at a reception. Wielding a barber’s razor, he removes the beards himself. We watch as Denis Diderot, in 1751, publishes the first installment of his 17-volume Encyclopédie, which downplays theology but dwells lovingly on the 18 manufacturing stages involved in the making of a pin; he stays one step ahead of religious censors still debating how many angels might dance on the head of one.

In London, in 1662, a successful haberdasher named John Graunt unwittingly creates the discipline of demography, using mathematical extrapolations from parish “bills of mortality” throughout Britain to estimate the country’s overall population (six million) and determine that it is growing. He is elected to the Royal Society. In 1744, also in London, the publisher John Newbery—who, like John Locke, favors an idea of education based on play rather than punishment—publishes A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, the first in a line of affordable books for children. Today’s Newbery Medal, honoring children’s literature, is named for him.

Don’t be put off by the imposing girth of The Enlightenment. One may wish that the book had been sold by the morsel—as shavings of truffle rather than total bulk weight. That said, alongside Diderot it seems compact. And Robertson has divided the book into a hundred or so mini-chapters, each an anecdote-inflected essay that slots into a larger framework. “Travel and Travel Writers.” “Sexual Relations Without Sin.” “Bringing Up Children.” “Genius.” You can’t buy The Enlightenment as shaved truffle, but you can read it that way.

Cullen Murphy is the editor at large of The Atlantic and the author of several books, including God’s Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World and Are We Rome?: The Fall of an Empire and the Fate of America