Fortune’s Many Houses: A Victorian Visionary, a Noble Scottish Family, and a Lost Inheritance by Simon Welfare

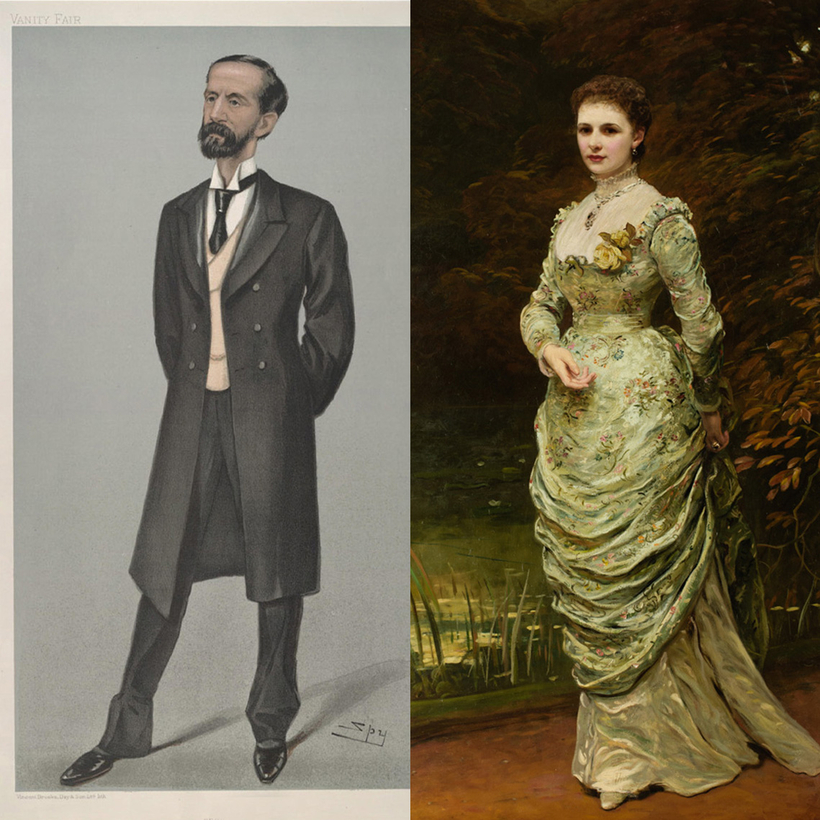

It may be that John Hamilton-Gordon, the most honorable first Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair, twice the lord lieutenant of Ireland, and the seventh governor-general of Canada, is best known to us moderns, if at all, for writing what the Scotsman newspaper once described as “the world’s worst joke book.”

The volume in question, Jokes Cracked by Lord Aberdeen, from 1929, is so hilariously unfunny that it became a cult item among bibliophiles, eventually warranting re-publication in 2013. A sampling: