Besides kicking a dog, there is no more effective way for a fictional character to provoke instant judgment than for a pregnant woman to smoke and booze it up. Well, maybe she could shoot heroin or skydive, but you get the idea—it’s a bad look.

Working that look in Greenwich Park is loud, flashy, inappropriate Rachel, whose attendance at a dreary London prenatal class jolts Helen Thorpe out of the lonely slog that her long-desired but high-risk pregnancy has become. Anxious, genteel Helen could use a friend, even if said friend wears sequined miniskirts and purple nail polish and declares, “Our mums all got smashed when they got pregnant,” before knocking back a glass of wine.

This new friendship has an unsettling effect on everyone close to Helen—her husband, her brother, and his pregnant wife, who met at Cambridge and live across the park in exclusive Greenwich. When Rachel, who’s young and single, temporarily moves into the gorgeous Georgian house Helen has inherited, the girl tips the household, already disrupted by an endless renovation, into chaos. And then, after a bacchanalian party and some harsh words from Helen, poof: Rachel and her mess are suddenly gone.

When the police get involved, a concerned Helen tries to figure out why Rachel inveigled her way into her life. Shiny object that she is, Rachel always draws the reader’s eye, but she is actually a distraction that prevents Helen from seeing a more insidious force that’s attacking her home from within.

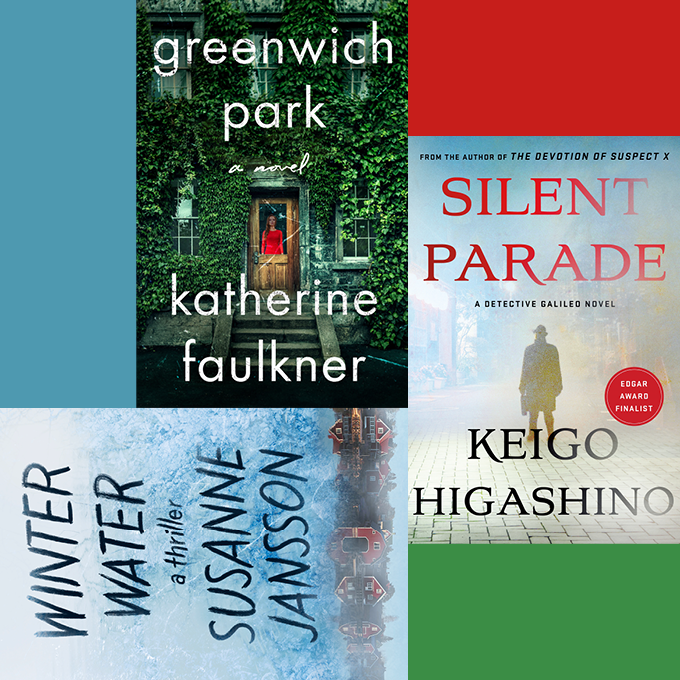

Domestic-thriller fans will be enthralled by Greenwich Park. First-time novelist Katherine Faulkner nails this deliciously nerve-racking tale of class tensions, sexual predation, and betrayal, played out in the most and least desirable real estate in London, from Greenwich Park to Hackney. A house, no matter how splendid and historically significant, is not always a home.

translated by Giles Murray

If you are drawn to intricate, elegantly devised mysteries that echo the golden age of Poirot and Miss Marple and haven’t yet encountered physics professor Manabu Yukawa, known to his admirers as Detective Galileo, you are in for a special treat. Keigo Higashino’s series featuring the sometime police consultant is a phenomenon in his home country of Japan, and his fourth Galileo novel, The Silent Parade, is a fine example of why.

The book begins three years after the unsolved disappearance of Saori Namiki, a young singer on the brink of a professional career whose parents run a popular restaurant in a Tokyo suburb. When her body is finally found incinerated in a burned-out house, the police focus on Kanichi Hasunama, a wily drifter who evaded justice once before, when he was on trial for the murder of a young girl. The case against him was flawed, so he kept his mouth shut and walked. Certain interested people in the Namiki-family circle, convinced he killed Saori, would like to make sure history doesn’t repeat itself.

Higashino meticulously lays the groundwork for the events that follow, creating a detailed portrait of the Namikis’ neighborhood that explains how its sense of community inspired otherwise decent people to choose a tortuous path to vengeance. The plan plays out during the biggest event of the year, a colorful procession with elaborate floats. By parade’s end, Hasunama is dead in his locked room, though how he died is unclear. Only Yukawa, whose intellect and expertise are ideally suited to this particular puzzle, can see past the shifting theories to the truth, though even he can be fooled at times.

At the beginning of each of The Silent Parade’s three parts, the author quotes John Dickson Carr, Agatha Christie, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to pithy effect. It’s fair to say that Keigo Higashino is their worthy successor.

translated by Rachel Willson-Broyles

This Swedish thriller with supernatural overtones is dominated by the sea, which has called for centuries to sailors, fishermen, travelers, the bereft … and children. Winter Water centers on the disappearance of a little boy, and the network of other losses revealed by his absence.

The life force in Winter Water is Maya Linde, an independent, 50-ish art photographer who has temporarily switched houses with a friend to stay in the seaside town of Orust, hoping to gain artistic inspiration from the ocean in winter. On January 11, a terrible thing happens. Maya’s neighbor Martin, who lives with his family in a fisherman’s cottage on the water, briefly takes his eye off his three-year-old son, Adam, and in that minute, the boy is gone. Adam is presumed drowned by the authorities, but his body is not recovered, leaving his family in limbo.

Martin shuts down, enclosing himself in an impenetrable bubble of grief. His only social contact is with Maya, who fills his empty days with games of chess and jigsaw puzzles. In time, Martin emerges from his fog with enough energy to learn something chilling about the house: years ago, it belonged to a family of three who drowned while ice skating off the shore—on January 11. As Martin and Maya delve further into this eerie coincidence, they make other, progressively stranger discoveries that keep leading them back to the water.

Susanne Jansson writes wonderfully about the teeming life above and below the surface of the sea, exploring its beauty and seductiveness through the eyes of Martin, who’s a diver. And from a storytelling point of view, the January 11 thread will keep you reading into the night. After finishing the book, I discovered that Jansson had died of cancer in 2019 at just 47, casting a tragic shadow over Winter Water.

Lisa Henricksson reviews mystery books for Air Mail. She lives in New York City