One thing never changes in Afghanistan, no matter who is in power. And that’s lunch.

Whether it is a meeting with an official or a visit to someone’s home, it almost always finishes up with an invitation to break bread.

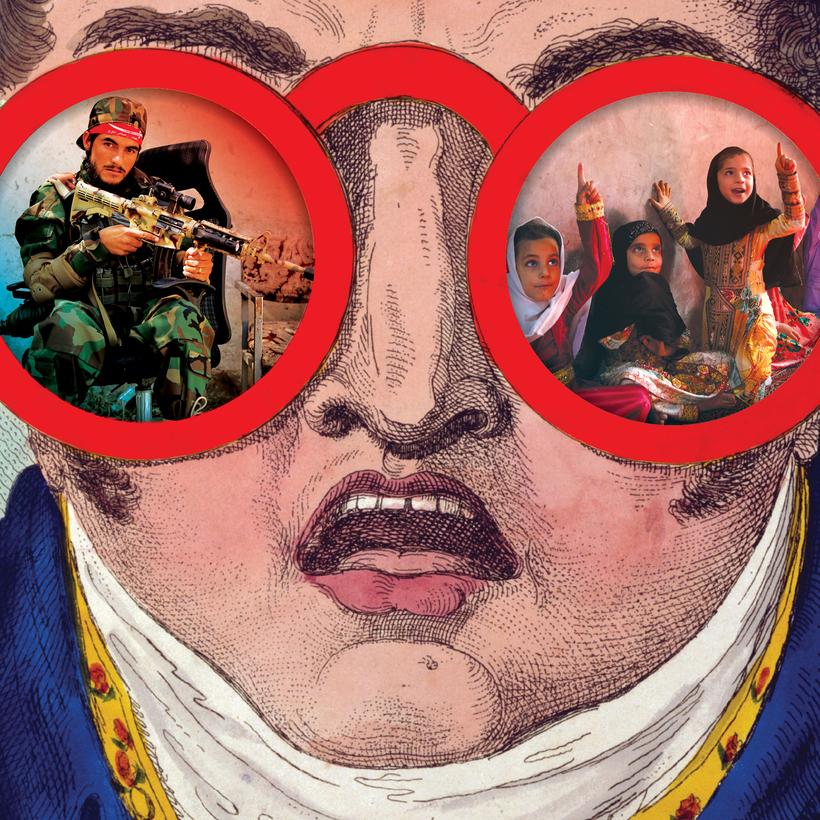

My lunch with a love-addled suicide bomber. Welcome to life in the new Afghanistan

One thing never changes in Afghanistan, no matter who is in power. And that’s lunch.

Whether it is a meeting with an official or a visit to someone’s home, it almost always finishes up with an invitation to break bread.