In 1953, Seymour Chwast and I were both working in the art department at Esquire. Seymour knew the Esquire job wouldn’t be as creative as some of his earlier jobs, but he wasn’t prepared for the utter lack of opportunity there was to do anything original or inventive. I was so pleased at keeping a job I barely noticed the hack nature of my work until Seymour showed up.

Over lunch, when he began kvetching again about the job, I suggested we do a promotion piece that we could mail to art directors ourselves. Maybe we could pick up some illustration work on the side. The Eisenhower stock market was booming. What could we lose?

That evening we stayed late at Esquire and planned our promotion piece. I suggested illustrating a parody of a 19th-century almanac, and Seymour liked the idea. He quickly came up with a French-fold four-pager with colored stock for a cover. It would fit into a common No. 10 envelope.

The name I suggested for our comic publication was The Push Pin Almanack, using the 17th-century spelling for “almanac.” We made Push Pin into two words because I was afraid that as one word it might be copyrighted by the Pushpin manufacturer.

We also decided that the last page would be devoted to two advertisements. One for any typographer who would set up the type free of charge, and one for a printer, who would also do it on the cuff in return for the two-inch ad we would design for him.

Since we and the printer and the typesetter were all going after the same clients—art directors in ad agencies—we were confident that we’d find some hungry small-timers to subsidize us. The United States Post Office was unlikely to give us free postage for an ad, but in 1952 first-class postage was still only three cents. Postage and paper stock would be our only cash outlay.

Because we planned to come out every month—we had big dreams—Seymour suggested we get Reynold Ruffins to do the third Almanack. Reynold, in addition to being the handsomest man in our class at Cooper Union, was also one of the most talented. He worked in a small design studio, but he was happy to join us in the evening.

While Seymour, Reynold, and Milton Glaser were at Cooper Union, they and other classmates had formed a design studio called Design Plus. They worked out of a small corner of a dance-rehearsal hall on 13th Street, not far from the school. There they designed place mats and greeting cards that they sold to Wanamaker’s department store.

That was when they were students. Now, Milton was in Italy, and many of the original group were no longer in New York. Those who remained in the city—namely Reynold and Seymour—continued to pay the small rent on their under-utilized space.

That little corner of a rehearsal hall, with its three drawing tables, now became the headquarters of The Push Pin Almanack, house organ for the nonexistent Push Pin Studios.

A Lucky Break

When Seymour’s issue came out, illustrated with his distinctive woodcuts, several art directors left messages on the studio phone offering him assignments. Two months later, Seymour and I got the luckiest break of all, although we didn’t see it that way at the time—we got fired from Esquire. I know you’ll assume it was because we were ignoring our job, but in fact the art director and most of the art department got canned as well. The higher-ups finally noticed that Esquire had become boring and dated and published corny cartoons.

Even before we were fired, I thought that the Almanack was something we could build a studio on. My admiration for Seymour’s talent was unlimited. I didn’t think I could contribute much at the drawing table, but I thought I could be the “outside man,” taking Push Pin’s portfolio to art directors, while Seymour and Reynold did the assignments. I would carry my flat designs in the portfolio as well, but I knew they wouldn’t bring in any jobs.

Seymour was hesitant about starting a studio, but finally agreed to chance it. Reynold had a job that he enjoyed and that paid well, and he could not bring himself to leave it for an endeavor that had little chance of succeeding. But he agreed to let us carry his drawings in our portfolio, and if assignments came his way he would execute them at night.

The first step in starting our studio was to apply for unemployment insurance. That would give us $35 a week until the jobs started to roll in. Today, when the subway costs $3 and The New York Times costs $3 and a movie costs $20, it may seem absurd to go to the unemployment office each week and stand in line for hours in order to collect so measly a sum. But in 1953, the Times cost five cents, and you could eat well at a restaurant with tablecloths and cloth napkins for less than $5. I might add that leaving a tip of just 10 percent was considered the norm. So, $35 was not an insignificant amount of money.

(Although prices were beginning to rise. That year the cost of a subway ride went up to fifteen cents, and because the city couldn’t figure out how to adjust the turnstiles to accept both a dime and a nickel, the subway token was created.)

The second thing Seymour and I had to do was find some cheap studio space that we didn’t have to share with dancers or anyone else. On 17th Street, just east of Fifth Avenue, we found a floor-through space in an old building. It had only a couple of inadequate radiators, and no hot water, but I was an old hand at living without such luxuries, so I left my $28-a-month apartment, and moved into our new studio. Aside from the drawing tables and lamps, and my bed, there wasn’t enough furniture to require a moving van, so we enlisted all our friends with cars to move us into our new quarters.

Although the building seemed to be waiting for the wrecking ball, we had one noteworthy neighbor. The Emergency Civil Liberties Committee (E.C.L.C.) was on the floor below us. It had been formed in 1951 because the American Civil Liberties Union refused to accept Communists as members and would not even defend many of them.

The E.C.L.C. founder and chief financier was Corliss Lamont, who bankrolled a lot of leftist causes. He could afford it. He was the son of Thomas W. Lamont, a partner and later chairman at J. P. Morgan & Co. However, Corliss, unlike his father, thought that Stalin was the hope of the world, and gave generously to every Communist cause. Judging by the dilapidated building in which he placed the E.C.L.C., Corliss must have been running out of money.

The Push Pin loft had three large windows facing north, and that’s where we put our drawing tables. There was a small room off to the side, large enough for a double bed and a chest of drawers, and an alcove containing a tiny refrigerator and an electric range with two burners. There was no shower and no hot water, but I could boil water for shaving. I can’t recall any closets, but I know I had two suits—my only qualification for being the studio’s representative—and they must have hung someplace.

The Eisenhower stock market was booming. What could we lose?

Needless to say, most of my family took a dim view of the course my life was taking, but my mother never said a discouraging word. “As long as you’re happy” was her refrain.

Getting to show art directors a portfolio was simple back then, since advertising agencies had art buyers. Some, like Young & Rubicam, had as many as three or four, and after looking at the kind of art you were peddling, they would send you to the art director whose advertisements could use that style.

There was also a book called Noble’s List that collected the names of all the art directors at magazines and book publishers. The easiest assignments to get were book jackets, record albums, and small spots for newspapers. There were 10 dailies in New York City then, including the Brooklyn Eagle and similar smaller papers.

On an average day, I saw as many as five art directors, and there was seldom a day when I didn’t pick up something for Seymour or Reynold. Once, even I got an assignment, a series of spots for the Times travel section.

No matter how much we were billing, Seymour and I never paid ourselves more than $65 a week, and the result was that our checking account soon hovered close to $2,000. We now needed an accountant. And then we heard that Milton had returned from Italy.

It had never occurred to me that Milton would be part of the studio Seymour and I had created. And it had never occurred to Milton that Seymour wouldn’t want him to be part of this new enterprise.

There was a somewhat tense meeting between the three of us one night. I made it clear that I preferred to continue with just Seymour. We were doing well without Milton. He, on the other hand, felt the partnership that he once had with Seymour was still binding, even though he had been in Bologna for a year on a Fulbright scholarship.

Since it was Seymour’s artistic talent that was at the heart of Push Pin, it was up to Seymour to decide whether Milt joined us or not. But Seymour refused to make a decision: “I’ve got to sleep on it.” Then Milton asked him, “Don’t you think I’ll make a significant contribution to this enterprise?” Seymour said nothing.

After Seymour and Milton left, I knew that Seymour would decide to bring Milton in. Once Seymour had thought it over, he’d realize what a monumental difference Milton would make to the studio. And, sure enough, the next morning Seymour told me just that. What I couldn’t foresee was the enormous positive effect that working with Milton would have on me.

Being able to put Milton’s drawings in the Push Pin portfolio brought an immediate change not only to the number of jobs I brought in, but to what they paid. Milton had a drawing style for every occasion. One was a witty version of 18th-century crosshatch etchings. It became enormously popular.

Within a few months, jobs were coming in without my even soliciting them. One of them was for a filmstrip for Pepperidge Farm bread, which was to be a history of the making of bread from ancient times to the present. It would need more than a hundred drawings, and it had a tight deadline. It paid big bucks. My partners told me to cancel all my appointments with art directors and get on my drawing board so we could get this job out on time.

I told them I didn’t think I could do it. Milton assured me I wasn’t going to have any problems. “All we’re going to do is copy art that has already been done about the making of bread,” he said. “It’ll be a snap.” And to prove his point, he handed me reproductions of ancient Egyptian paintings depicting people making bread. Anybody can do fake Egyptian art, even a schlemiel who has forgotten how to draw.

Back to the Drawing Board

The ancient Egyptians outlined all their figures in black line, just as I did when I was a boy. Back then I would first draw my images in pencil on paper, and then go over the pencil lines with pen and waterproof India ink. When the ink drawing was finished, I would erase the pencil lines with a kneaded eraser, and—presto!—have a neat line drawing, ideal for comic strips.

That was—and is—a perfectly good way to do a pen-and-ink drawing. It’s the way Al Hirschfeld and David Levine did it. But Seymour and Milton used a different method.

They would get a pad of translucent bond paper (16-pound bond is best) and then start sketching in ink, not pencil. If all the elements weren’t quite right—and they never were the first time—they would tear the top page off the pad and slip it under the new blank sheet. Able to see the previous sketch through the thin bond paper, they kept refining until they had a sketch they could copy to a finish. After they had copied it in ink, they mounted the finished drawing, which was on light bond paper, onto stiff paper or board, and added watercolor.

This method is called slip-sheeting. And I found that my drawings were less stiff with this method than if I carefully followed a pencil outline. (Caution to would-be illustrators: Do not use rubber cement to mount bond paper. It will yellow and bubble in a year. Buy a mounting machine that will adhere the bond paper to an acid-free board. If you prefer drawing on quality paper rather than thin bond paper, buy a light box that will allow you to see your sketch through the opaque paper.)

By the time the Pepperidge Farm filmstrip was finished, I realized that I had produced almost as many drawings as my partners had, and that mine weren’t so bad. The experience reminded me of how much I used to enjoy drawing—before I went to art school.

Anybody can do fake Egyptian art, even a schlemiel who has forgotten how to draw.

Soon it was necessary for us to hire help. One was an art-school grad who could assist us with the mechanical aspects of our assignments. Another was an ex-girlfriend of Seymour’s who could send out invoices, answer the phone, and do anything else we no longer had time to do. The salary we offered was too low, she said, but if we agreed to keep her off the books, so she wouldn’t have to pay taxes, she would take the job. Her name was Elaine. She seemed capable. She got the job.

Now that I’d proved to myself I could still draw, the job of showing our portfolio to art directors ceased to be something I looked forward to. Getting into a suit and tie every day was a nuisance. Remember, this studio didn’t have a shower or a closet. Making myself presentable and odor-free wasn’t easy—and dressing like a slob would not become fashionable until the 60s.

More to the point, I wanted to be a full-time artist. One of my book jackets had gotten into the annual Art Directors Club exhibition. I no longer felt like a complete no-talent. Milton and Seymour were amenable to hiring a salesman to take over my job as rep, but who could we get?

Elaine said she had a friend who was in charge of promotion at the Royal Liverpool Insurance Company, and he might be able to give us some work. His name was Warren Miller, and he was impressed with what he’d seen in the Push Pin portfolio. I, in turn, was impressed with his clipped speech and sartorial elegance, as well as his way of holding his cigarette and his deadpan wit. He must be English, I thought.

It turned out he was from Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and by the time he had looked through the portfolio it was almost noon, so I impulsively invited him out to lunch. Another surprise was to discover that he was a published writer who was none too happy working at Royal Liverpool in order to support his estranged wife and two daughters.

Here, I thought, was someone who could represent Push Pin far better than I could. Beguiled by his soft-spoken voice and privileged manner, no one would imagine that the Push Pin “studios” was a loft with insufficient heat in a run-down walk-up. I convinced him that working for us would not only be more fun, it could also mean more money.

He came to the studio after five and met with Seymour and Milton. As the elegantly attired applicant in his early 40s sat down to face the sloppily dressed proprietors in their mid-20s, the incongruity of the scene was not lost on any of us. Nevertheless, there was an almost immediate understanding that his joining us would be advantageous to one and all.

We agreed to meet Warren’s salary demands and took a certain pride in knowing that Push Pin Studios had just outbid the Royal Liverpool Insurance Company—with offices in London, Dublin, and New York—for his services.

My career as Push Pin’s representative was now over. And so were my evenings of being alone after Seymour and Milton left to go home. Elaine, our bookkeeper, and I had become an item. Most nights I ended up in her cozy apartment, which had a television set, a double bed, hot water, and a shower. Things were looking up.

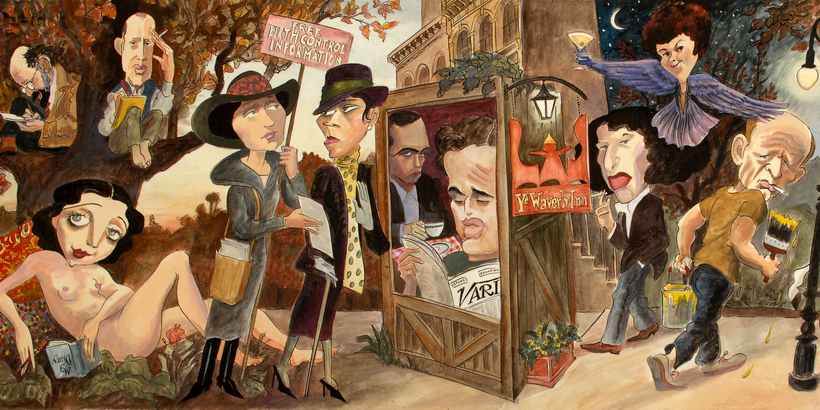

Edward Sorel’s illustrations have appeared everywhere from The New Yorker to New York magazine, Esquire, and Vanity Fair