Though Harry Bosch and Renée Ballard get equal billing above the title, this book really belongs to Detective Ballard, Bosch’s spiritual sister and fellow maverick. Whether this indicates the passing of the torch, or just a temporary shift of the spotlight, it feels like the right approach at the right place and time, which is Los Angeles at the turn of 2021. Between the pandemic, social unrest, and pervasive homelessness, the city is seething.

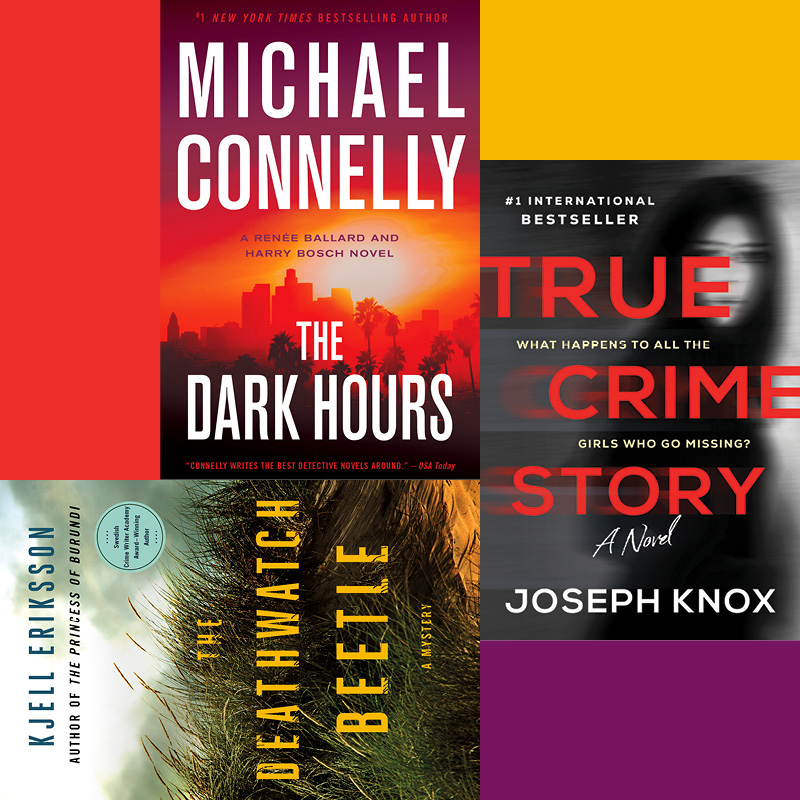

Still working the midnight shift in Hollywood, Ballard continues to chafe against the L.A.P.D.’s sexism, politics, and incompetence, but she loves the freedom afforded by the “late show.” In The Dark Hours, she switches back and forth between two cases: the murder of a well-liked auto-body-shop owner during a New Year’s Eve celebration, and an ongoing series of nocturnal rapes perpetrated by a tag team known as the Midnight Men. Though Ballard has no partner, she consults her retired guru, Bosch, who’s intrigued because the murder is linked to one of his old unsolved cases.

One of the first mystery writers to acknowledge the pandemic in his work, Connelly integrates it here in quotidian ways: Ballard, a conscientious mask wearer who is too young to get the vaccine at the time, drives Bosch to Dodger Stadium to get his first dose and even adopts a pandemic pup in the midst of the mayhem.

And with the insurrection at the Capitol, cops are on the alert for related uprisings in their own territory. Since the Midnight Men are on the prowl throughout the book, that case feels more urgent than the murder, but the exploitative dealings that led to an innocent man’s death have their own quiet power to devastate. Although The Dark Hours is Bosch’s 23rd outing, Connelly’s arsenal of fresh angles on crime remains inexhaustible, as does his passion for social justice.

It can be tricky to get your bearings in True Crime Story. The English crime-fiction writer Joseph Knox puts little daylight between himself and his unreliable narrator of the same name, borrowing from the Anthony Horowitz playbook by sharing his doppelgänger’s background, publisher, and looks. But where Horowitz’s writer character is charmingly self-deprecating, Knox’s stand-in is intentionally not.

The novel purports to be Knox’s collaboration with Evelyn Mitchell, an aspiring true-crime writer he meets at a book signing. They subsequently correspond about her obsessive research into the 2011 disappearance of Zoe Nolan, a promising young singer who’d just begun studying at a university in Manchester when she vanished without a trace. When circumstances make it impossible for Mitchell to complete the project, Knox brings it home with a dramatic flourish.

Told via Mitchell’s interviews with friends and family, e-mails between Knox and Mitchell, newspaper clippings, and so on, the book is a constantly shifting history of Nolan’s fraught life and times. Along the way, a few skeletons pop out of Knox’s closet, keeping the reader skeptical about the nature of his involvement.

It’s tempting to speed through a book constructed of bite-size pieces, but the whiplash twists and turns of the plot and the voices of Nolan’s friends (mighty clever and emotionally astute for people in their mid-20s who knew her for only three months) demand more careful reading. True Crime Story may be a satire of the genre, but it takes its plot seriously. Though some of the speakers may come across as insufferable at first—they were snotty 24-hour party monsters in college—Nolan’s absence and the intervening years have altered them in ways that are just as interesting as any revelation about her fate.

Ann Lindell’s career trajectory from Stockholm homicide detective to small-town cheese-maker might seem like a comedown, but it suits her just fine. Her innate curiosity remains, however, and when she goes on vacation to the island of Gräsö, in Roslagen, she’s struck by the story of Cecilia Karlsson, a young woman who disappeared five years earlier, and begins making casual inquiries in the town.

Nearly everyone she speaks with is a little odd, resentful, depressed, or alcoholic, and possibly all four, the result of spending their lives on a rural Swedish island. Karlsson was too attractive—“she radiated tons of those pheromones,” says an observer—too smart, and just generally too big for Gräsö, so though it was news when she vanished, most of the town has moved on.

Except, of course, for her parents, a former Olympic-level runner and an archer who are quietly eating each other alive in her childhood home, and an old boyfriend devoted to lawn care and liquor who still carries a torch for her. Lindell seems to be the only one interested in Karlsson’s possible involvement in an old case that looks to her more like murder than accidental drowning, but the ex-cop’s presence seems to shake something loose, and Gräsö’s secrets gradually start to emerge.

Kjell Eriksson knows how to burrow inside a community and carefully, thoughtfully, with a deadpan Swedish sense of humor, expose its layers of repression and potential for violence. Anyone expecting the chain saw wielded by the ex-boyfriend to go off like Chekhov’s gun in the third act will be disappointed. It’s not that kind of book. Think more in terms of the titular insect, which gets into the walls of old wooden houses and taps a steady countdown until someone dies.

Lisa Henricksson reviews mystery books for Air Mail. She lives in New York City