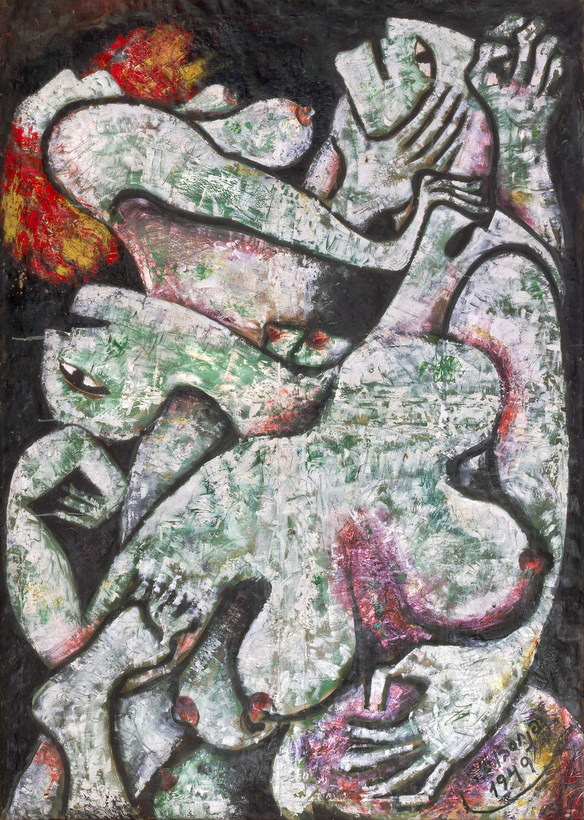

Maryan S. Maryan’s early painting Crematorium at Auschwitz (1949) depicts an expressionistic tangle of greenish limbs, grasping hands, reptilian faces, and the flames of an incipient furnace. It was created in Israel when the artist, who was born in Poland in 1927 and miraculously survived Auschwitz (though not without losing a leg), still called himself Pinchas Burstein. The painting was one of several Holocaust-themed pictures that featured in the young Burstein’s first solo exhibition, in Jerusalem in 1950.

“Those paintings went missing, and no one knew where they were,” says Alison M. Gingeras, the American curator who eventually tracked them down in private collections. Their discovery is important in the context of what Maryan achieved. “I have just done an exhibition of another artist, called Erna Rosenstein, who was also Polish,” Gingeras says. “The two of them are among the first to create paintings that directly depict things they witnessed during the Holocaust.” In the 1950s, Maryan, who was born into an Orthodox Jewish family, changed his name to rid himself from the persecution the Nazis had attached to it, but he would always be shadowed by the Shoah.