The Gilded Edge: Two Audacious Women and the Cyanide Love Triangle That Shook America by Catherine Prendergast

When the 25-year-old Nora May French went home to self-administer an illegal abortion, in March 1907, she walked on shaky ground. Her San Francisco neighborhood, which had been devastated by an earthquake less than a year before, was regularly rattled by a nearby quarry. And there were other tremors, too. The prosperity that the U.S. had enjoyed since the 1870s was teetering, and many would be sent into ruin that year.

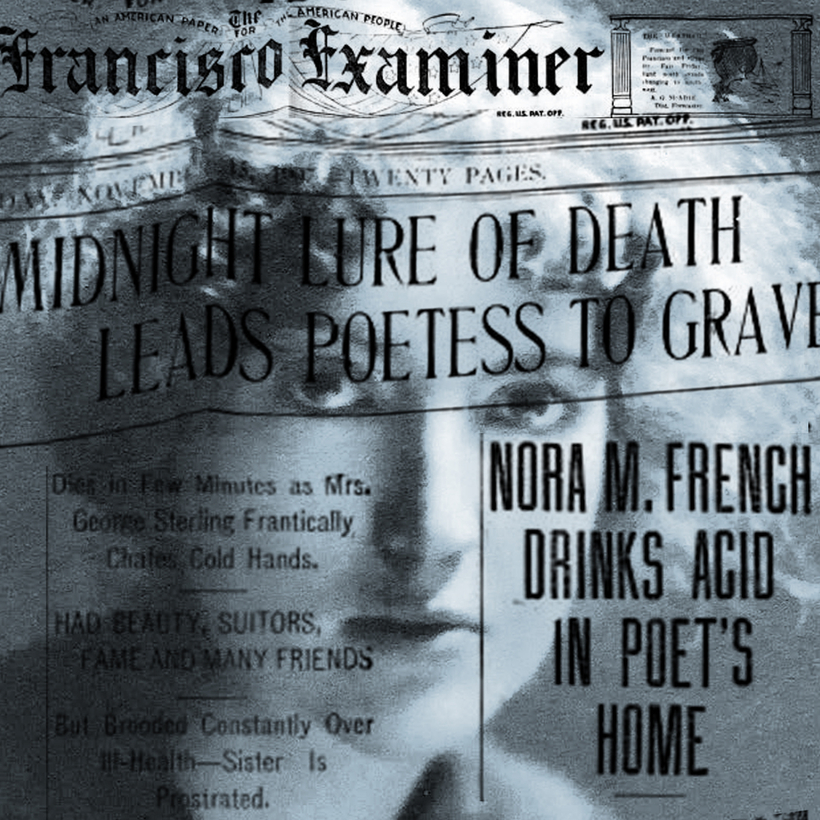

As an unmarried, working woman, French knew all about precarity. And she must have known that, without the expense of a doctor to help her, she was putting her life at risk. As it turned out, she would survive the abortion but not the year.