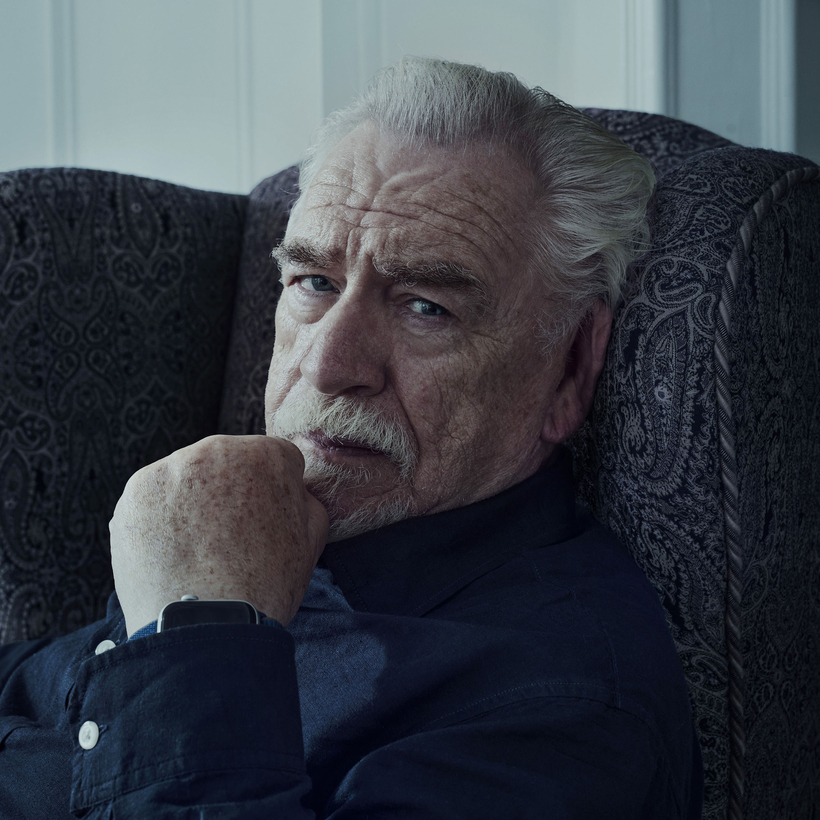

Somewhere toward the middle of his new memoir, Logan Roy—O.K., that’s actually Brian Cox—observes, “We actors are whores for praise … capable of killing our offspring in return for validation and living only for applause.” At the risk of feeding the beast to spare the offspring, I have to say this volume is simply a delight, so much so that it’s tempting to consume it in one sitting. It’s snarky and cutting in a sometimes take-no-prisoners way as befits a waif brought up poor on the hardscrabble streets of Dundee, Scotland, but almost always funny.

About his youth, and trying to figure out what he was going to do with his life, he writes, “I never thought, Oh, maybe I might like to be a dentist, or run a garden centre, or become a cobbler. It was always just, I want to be Spencer Tracy or Danny Kaye or Cary Grant or Bob Hope. I want to be an actor.” But he was none of them. The transformative moment came when he saw Albert Finney in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. “That was all about working-class people—people like us,” he recognized, and thought, “If that guy up there can do it, I can do it, too.” The kitchen-sink school of 60s actors such as Finney, Tom Courtenay, Richard Harris, Peter O’Toole, and Alan Bates offered him a way of “escaping that great Damoclean sword of wretched poverty.”