Walking with Ghosts by Gabriel Byrne

When I think of memorable Hollywood autobiographies—particularly those written by unshackled veterans of the industry, both jaded and jocular—I think of David Niven’s bombastic romp, The Moon’s a Balloon; Christina Crawford’s gothic nightmare, Mommie Dearest; Robert Evans’s coked-up tell-all, The Kid Stays in the Picture; and Julia Phillips’s even more coked-up tell-all, You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again.

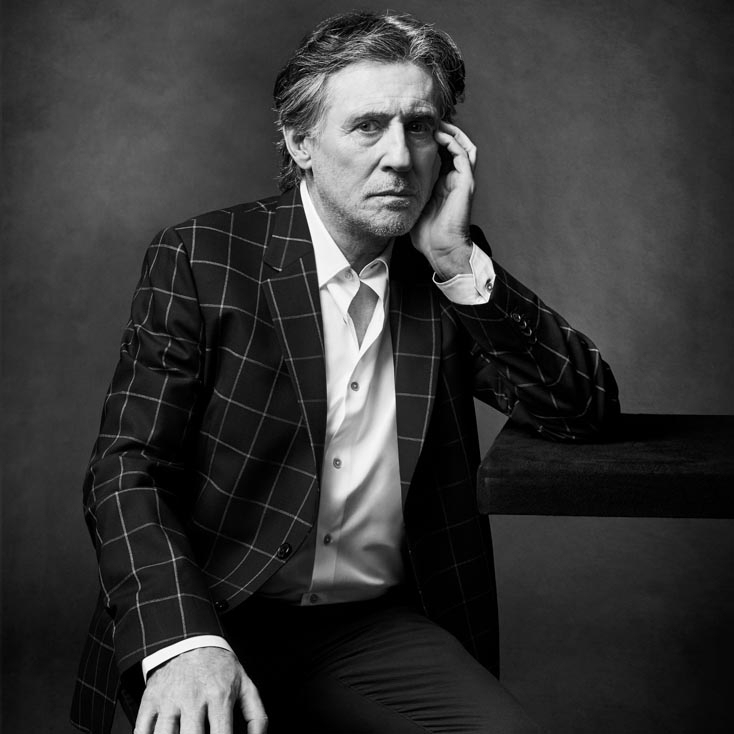

Technically speaking, Gabriel Byrne’s Walking with Ghosts—a remarkably intimate new memoir by the Irish actor and star of Miller’s Crossing, The Usual Suspects, and HBO’s In Treatment—belongs on a shelf with the aforementioned titles, but it is, as Yeats would say, of a different kind.