To call Ed Sorel an illustrator would not only be a disservice to the man but to the entire discipline. Fairly speaking, he is the dean of American illustrators, a lodestar for an entire generation of satirists and caricaturists.

Sorel began his career as a student at Cooper Union and, after graduating in 1951, founded the graphic-design firm Push Pin Studios with his former classmates Milton Glaser and Seymour Chwast. In the intervening decades, he has drawn and written for every important magazine in existence (and some that no longer are), Time, Harper’s, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, New York, and Vanity Fair among them. He has painted murals at the Waverly Inn and the Monkey Bar. He has reviewed the books and exhibitions of his fellow artists and written books himself, including Mary Astor’s Purple Diary—a rollicking account of the 1936 sex scandal involving the Hollywood starlet—and an upcoming memoir. So far, his career has plagued 13 presidential administrations—that Donald Trump occupied that unlucky 13th slot is a coincidence that calls out for one of Sorel’s sparklingly biting captions.

A lodestar for an entire generation of satirists and caricaturists.

Like all great satirists, Sorel has a gimlet eye. But unlike most of them, he is not wicked. Sorel’s drawings display a certain degree of sympathy for even the most wretched of subjects, and though he isn’t forgiving of human folly, he certainly grasps that it lurks within all of us. In satire, the only thing more dangerous than a born draftsman who is steeped in popular culture is a highly literate born draftsman who is steeped in popular culture. Sorel falls into the second category, and in his pursuit of pictorial justice he considers every detail and deems nothing too sacred for his pen, from Hollywood to politics, to the arts and literature and beyond. He is moral without being moralistic, critical but not bitching, and damn good at what he does.

So far, Sorel’s career has plagued 13 presidential administrations—that Donald Trump occupied that unlucky 13th slot is a coincidence that calls out for one of Sorel’s biting captions.

Truly, Sorel is much more than an illustrator: he is a style and a class and a genre unto himself. Here, the artist shares his favorite illustrated books—outside the children’s sphere. “I’d lose my mind trying to choose between William Steig, André François, Tomi Ungerer, Barbara McClintock, Edward Ardizzone, and Arthur Rackham,” Sorel says. “To keep my sanity, I’ve limited myself to books for adults—one from the 19th century, one from the 20th, and one from the 21st.” —Nathan King

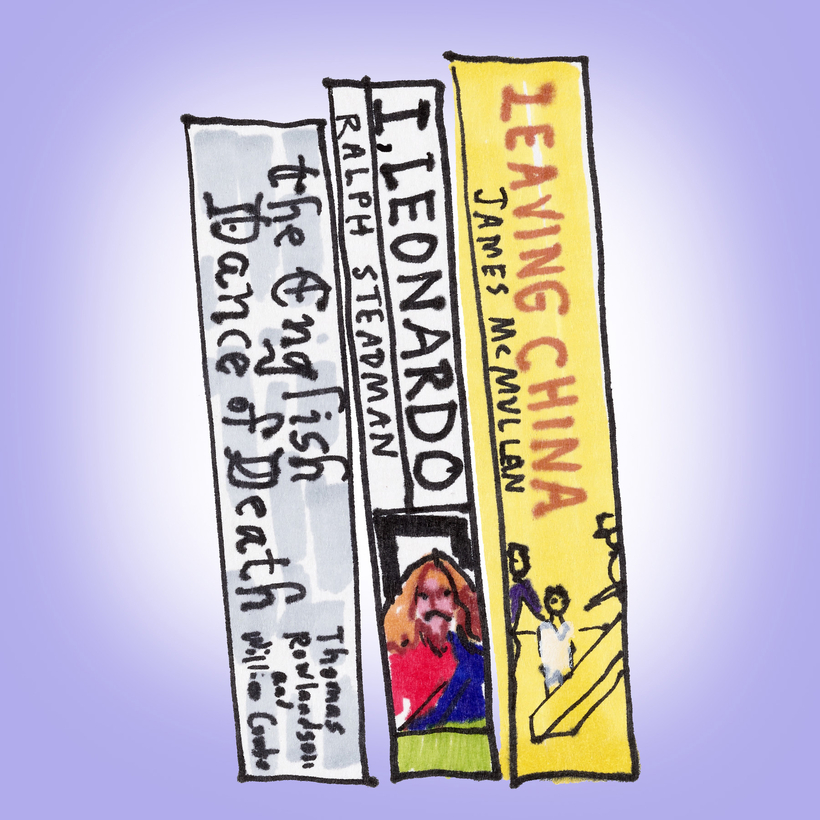

The English Dance of Death, by Thomas Rowlandson and William Combe

By 1800, London had cornered the market on great caricaturists. At the very top of that pyramid were James Gillray, William Hogarth, and Thomas Rowlandson. Rowlandson attended the Royal Academy School for artists, then struggled for a while as a portrait painter until his uncle died and left him enough money that he could devote himself to gambling, drinking, and fornication. When the money ran out, the success of his friend James Gillray showed him he could earn a living doing caricature.

Although Rowlandson’s political etchings were enormously popular—especially the ones ridiculing Napoleon—the artist preferred making prints satirizing the lifestyles of the upper and lower classes. These were later published as books, the best of which is The English Dance of Death, issued in 1815. Rowlandson’s ease of draftsmanship makes these scenes of imminent death somehow hilarious. They were accompanied by William Combe’s verse, but the less said about that the better. Happily, there are facsimile copies of this book easily available.

I, Leonardo, by Ralph Steadman

Art Young’s Inferno: A Journey Through Hell Six Hundred Years After Dante is such a brilliant idea for a book—capitalism as hell—that I very much wanted to call it a favorite. But as much as I share Art Young’s political viewpoint, this 1934 book is written with such dated Daily Worker jargon that I’ve changed my mind and chosen instead a book illustrated by Ralph Steadman in 1983. Its title is I, Leonardo.

Steadman has illustrated dozens of books written by others—Alice in Wonderland, Animal Farm, Treasure Island, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas—but in writing I, Leonardo he has given himself material that has inspired his best work. Writing in the first person, Steadman imagines that he is Leonardo da Vinci, and that gives him the chance to draw inventions that Leonardo never dreamed of, such as the mechanical shaving machine, seen above. Steadman’s panoramic paintings of 15th-century Italy are stunning, and his writing is as inventive as one of Leonardo’s own contraptions.

Leaving China: An Artist Paints His World War II Childhood, by James McMullan

Now that I’ve come to the 21st century, I have no second thoughts about which book to choose as my favorite. Leaving China, by James McMullan, is far and away the most significant illustrated book of this young century. Though published in 2014 as a book for young readers, McMullan’s memoir will be best understood by adults. It begins in the port city of Chefoo, China (now known as Yantai), where his father, the son of English missionaries, owned a prospering trading company. Young Jim’s luxurious life in Chefoo, with servants galore, ended when the Japanese Army occupied the city in 1937. The book then becomes an exciting story of his escape, by way of India and Canada, to the States.

We have all become so accustomed to cold, computer-generated illustrations in magazines and books that McMullan’s warm, beautifully drawn paintings may strike some as being from a past century. But a discerning eye will recognize them as being not only contemporary but truly innovative.