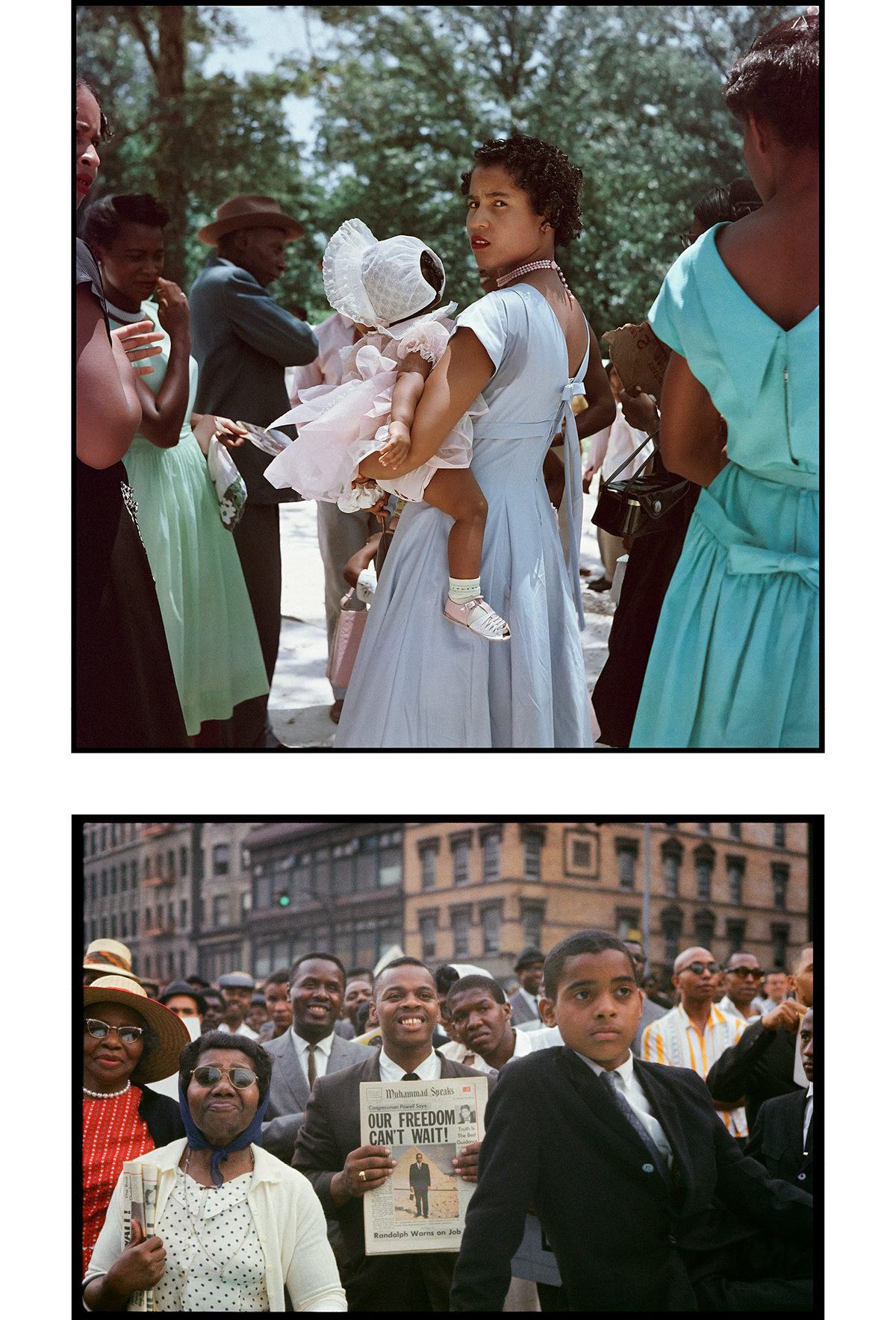

On the long walk into central London to see the Gordon Parks show at the Alison Jacques Gallery — I will use public transport soon enough, but I’m not man enough yet — I was surprised to see a giant billboard outside Kentish Town station festooned with the names of Hamed Maiye, Ashton Attzs, Joy Yamusangie, King Owusu. Beside each name was an artwork. Beside each artwork a declaration: Black Lives Matter.

There’s a powerful wind blowing across the land. It could be the wind of change. We’ll see. What it certainly is is the wind of pertinence. Only rarely as an art critic do you feel an unstoppable force pushing art in a clear direction. It’s certainly happening now. The most potent, most insistent, most important and best art being made is being made by Black artists.