On the night of December 5, 1956, an estimated 50 million Americans tuned in to Twenty-One, the most popular of the many quiz shows that dominated that early age of US television.

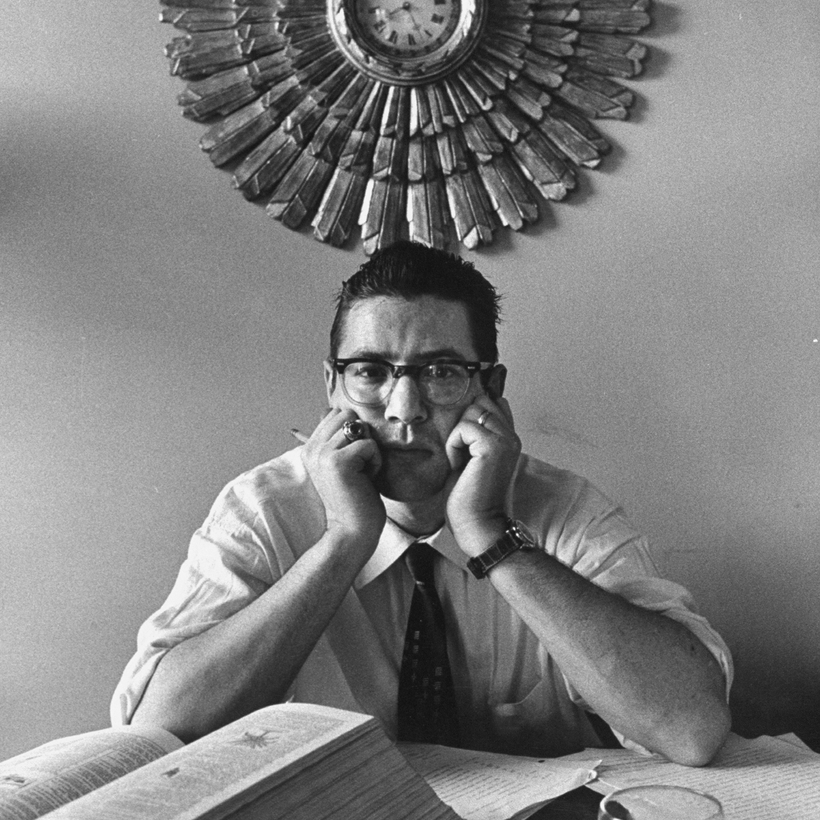

Over the previous eight weeks a stocky, nerdy and unappealing character named Herb Stempel had accumulated nearly $70,000 in winnings. All that day NBC had ratcheted up the tension by interrupting its programs to ask: “Is Herb Stempel going to win over $100,000 tonight?”

As he sat sweating in a glass booth, Stempel was asked a relatively simple question: which film had won the previous year’s Oscar for best picture?

He sighed, bit his lip and mopped his brow. Then he gave the wrong answer: On the Waterfront, not Marty.

Stempel’s reign was over, and a new star was born. Charles Van Doren, his opponent that night, was everything Stempel was not — tall, good-looking, personable, Ivy League-educated and from a distinguished literary family. He went on to become America’s heartthrob, the most popular contestant on that or any other quiz show, winning $129,000, worth more than $1 million today, over 15 weeks before Stempel finally gained his revenge.

Embittered at the way Twenty-One had used him, Stempel went public. He told newspapers, prosecutors and congressional inquiries how the show had been rigged. He revealed how he and other contestants had been fed the questions and answers, told when to win and when to lose, and even coached on how to perform.

Van Doren and the quiz show industry were disgraced. President Eisenhower called the deception “a terrible thing to do to the American public”. John Steinbeck, the novelist, lamented “the cynical immorality of my country”. Television lost its innocence in what one critic called the “moral squalor of the quiz show mess”.

Herbert Milton Stempel was born in the Bronx in 1926. His father, Solomon, a postal clerk, died when he was seven. Thereafter his mother, Mary, who suffered from high blood pressure, raised Herb and his older sister on welfare payments, but he had one talent going for him: a prodigious memory.

Not only did he represent his elementary school on a radio quiz show, he also represented the prestigious Bronx High School of Science in general knowledge contests against other New York schools, and was victorious. He claimed to have an IQ of 170 and a photographic memory.

After leaving school in 1944 he joined the US army for seven years, serving a month in Europe at the end of the war before training in counterintelligence. By the early Fifties he was back in New York, studying at City College courtesy of the GI Bill and struggling to support a wife, Tobie, and their infant son, Harvey.

Eisenhower called the deception “a terrible thing to do to the American public”. John Steinbeck, the novelist, lamented “the cynical immorality of my country.”

That was when he first watched Twenty-One. He found the questions easy and applied to be a contestant. “I have thousands of odd and obscure facts and many facets of general information at my fingertips,” he wrote. He took a test, and got a record 251 of the 363 questions right.

To Dan Enright, the show’s producer and co-creator, contestants whom viewers would hate were as valuable as those they would love. Of the unprepossessing Stempel he said: “If you saw him, you had no choice but to root for him to lose.” Enright visited his Queens flat and asked: “How would you like to win $25,000?”

“I immediately understood what he was saying,” Stempel recalled years later. “Once I said ‘Who wouldn’t?’ I became part of the game show hoax.”

Enright turned Stempel into a caricature of an impoverished nerd. He dressed him in an ill-fitting suit and frayed shirt. He gave him an unstylish haircut. He made him wear a cheap watch whose loud ticking would be picked up by the microphone to increase the tension. He showed him how to stumble over answers, wipe sweat from his brow and behave obsequiously to the quiz master. He was told which questions to answer correctly, and which to get wrong. “From the time you stepped into the isolation booth, you knew exactly what you had to do,” Stempel recalled decades later.

Stempel won six weeks in succession. He reveled in the fame and approbation. Yet when the ratings began to drop, the producers decided Stempel had to go. Van Doren, a teacher of English at Columbia University, was brought on to the show to challenge him. “Once I saw him, I knew my days on the show were numbered,” Stempel said. “He was tall, thin and Waspy, and I was this Bronx Jewish kid.”

He was allowed to tie with Van Doren for the next two shows, then told to “take a dive” on the third. Stempel begged for a clean fight with his privileged opponent, but the producers said no. He briefly considered defying them by giving the right answer, but Enright promised him more TV work if he did as he was told. It was all the more galling because he had watched Marty three times and loved the film.

Enright turned Stempel into a caricature of an impoverished nerd. He showed him how to stumble over answers, wipe sweat from his brow and behave obsequiously to the quiz master.

Stempel subsequently lost most of his winnings in an investment scam, along with $10,000 that he made by betting on Van Doren’s success because he knew he had been scripted to win.

When the TV work that Enright promised failed to materialize he decided it was time for some bean spilling. He told newspapers how quiz shows were rigged, but they refused to run his story without corroboration. It was only two years later, when another contestant complained after seeing a rival’s notebook with the answers written in it, that his charges gained credence. The Manhattan district attorney launched an investigation, a grand jury heard damning evidence and in 1959 the House committee on interstate and foreign commerce held hearings that proved almost as riveting as the show. Van Doren and 16 others were indicted.

Thereafter Stempel vanished from public view, working as a legal researcher for the New York City transportation department. His first wife died in 1980, and his second marriage, to Ethel Feinblum, ended in divorce. His son survives him.

In 1992, Stempel appeared in a PBS documentary called The Quiz Show Scandal, during which Enright apologized profusely for the way he had plucked Stempel from obscurity, used him and dumped him. Two years later Robert Redford made the film Quiz Show, employing Stempel as a consultant and giving him a cameo role as a minor contestant being interviewed by a congressional investigator. His own character was played by John Turturro.

Stempel began giving lectures and interviews, one of which was recorded in the same NBC studio in the Rockefeller Center where Twenty-One was staged. He again achieved a measure of celebrity. And he had the satisfaction of outliving Van Doren, who died almost exactly a year before him at the same age.

Herbert Stempel, quiz-show contestant, was born on December 19, 1926. His death from undisclosed causes, on April 7, 2020, aged 93, was announced belatedly