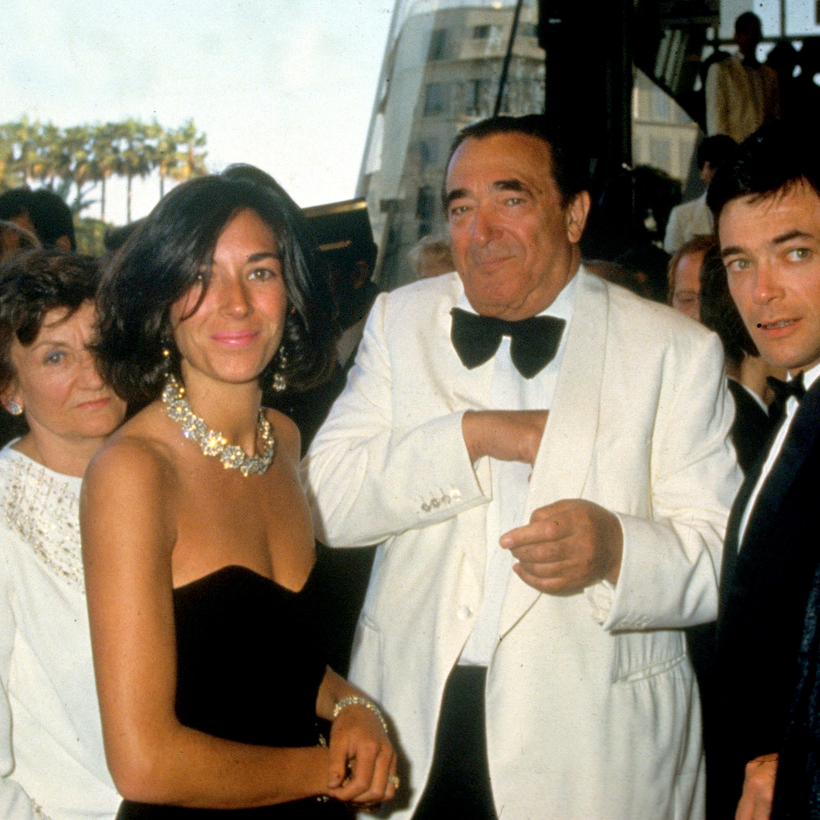

I remember Ghislaine Maxwell as a child in the 1970s, when she was not much younger than some of her accusers were when she is alleged to have been involved in their sex trafficking. She seemed a distant, beautiful, rather threatening figure, already wielding great power with little care.

Two years older than me, Maxwell was an exact contemporary of my sister at Oxford High School in leafy north Oxford, an unlikely figure of glamour among the dons’ daughters, a bird of paradise in a successful academic battery farm. Dame Cressida Dick, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police and Maxwell’s polar opposite, morally and legally, was also a pupil. I wonder what Britain’s top police officer makes of her fellow alumna, now Britain’s most notorious accused pimp.