Louis Fabian Bachrach Jr. was waiting. The patriarch of Bachrach Studios had flown from Boston to Washington in 1959 to retake Senator John F. Kennedy’s portrait. An earlier sitting had been disappointing—the photographs were out of focus or showed Kennedy, who suffered from debilitating back pain, posing awkwardly. None were usable. Fabian, as he was often known, agonized over his failure to capture Kennedy. “It really ate at him,” recalled his son Robert, also a photographer, who, years later, would preside over the end of the family business.

When the young senator finally arrived—eight hours late—the restless presidential hopeful announced that he could spare the photographer only 10 minutes of his time.

But it was worth the wait. Of the six photos taken that day, one in black and white and another in color, with Kennedy seated in a leather armchair before an American flag, would soon become the official presidential portrait, ubiquitous during Kennedy’s presidency and after, gracing the covers of books, magazines, and even record albums that quickly appeared after his assassination. (More recently, it was featured on the back of Bob Dylan’s new album, Rough and Rowdy Ways.)

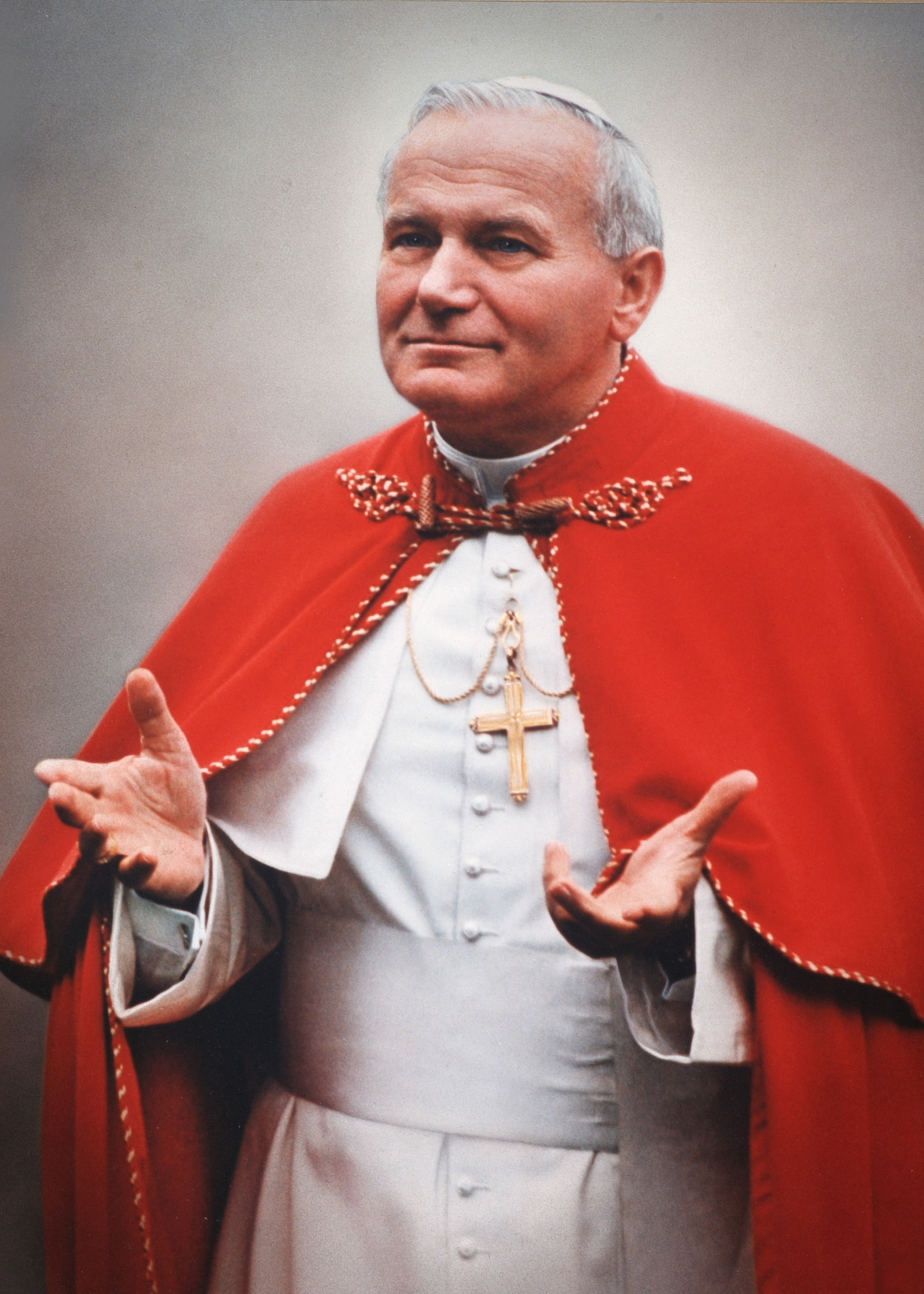

Every president from Abraham Lincoln through George H. W. Bush sat for the Bachrach camera, as well as a Who’s Who of the American Century: Joe DiMaggio, Muhammad Ali, Robert Frost, Buckminster Fuller, Richard Avedon, James Dickey, Duke Ellington, Julia Child, Henry Kissinger, Dizzy Gillespie, Barry Goldwater, Billy Graham, Colin Powell, William F. Buckley, Amanda Burden, Richard Nixon, and assorted Kennedys, beginning with Joseph and Rose. John D., Nelson A., and just about all the Rockefellers. The holy trinity of CBS: William S. Paley, Walter Cronkite, Mike Wallace. Add to the mix Ralph Nader, Julius Irving, Hank Aaron, Zubin Mehta, John Kenneth Galbraith, Malcolm Forbes, John Cheever, John Cage, Leonard Bernstein, and Charles Addams.

Besides foreign and American dignitaries, actors, musicians, athletes, brides, socialites, and debutantes, the bread-and-butter clients for Bachrach Studios were executives. A Bachrach portrait was essential to accompany news of promotions or partnerships, and to hang solemnly over the long table in corporate boardrooms. In the Mad Men era, especially, you hadn’t arrived until you had your Bachrach photograph taken. As Carol Squiers wrote in an article about the studio for Manhattan Inc., “In real life you may be an ugly duckling, but your portrait will reveal a captain of industry.” A New Yorker cartoon from 1966 depicts a businessman at his desk telling his secretary over the intercom, “Call Bachrach, Miss Chadwick. I feel ready today.”

The Studio

The first Bachrach Studio was opened in Baltimore in 1868 by 24-year-old David Bachrach Jr., a stringer for Harper’s Weekly. As an apprentice to a portrait photographer, he had photographed the crowd listening to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in 1863. His business prospered as David pursued the rich and famous, earning him the sobriquet “dean of portrait photography.” He died in 1921.

David’s son, Louis Fabian, expanded the business throughout the 1920s, eventually opening 48 studios across 12 states. After the Depression hit, many had to be closed, but not the New York studio, which he’d opened in 1925 and later moved to a five-story redbrick building he had constructed at 54 East 52nd Street.

In the Mad Men era, especially, you hadn’t arrived until you had your Bachrach photograph taken.

The interior was strictly old-school—clubby leather and wooden desks—with Bachrach photographs on every cabinet, table, and wall. In the 70s and 80s, Gerald Ford’s and Meryl Streep’s portraits stared down among matte photographs of unnamed, beaming brides. The photographic studios and dressing rooms were on the fifth floor, with a different style, color palette, and lighting for men and for women. Boardroom paneling was used for the men’s backdrops. For the women, “Fragonardian cloud-and-foliage shapes” provided the desired, gauzy effect, as Douglas Collins noted in his book Photographed by Bachrach.

Fabian took over after his father’s death. He shot the men’s photographs while his brother, Bradford, photographed the women’s. They often completed seven sittings in a day, typically lasting 45 minutes to an hour each. (Though some, like Kennedy’s, were dashed off if the subject was too busy, or too important, to sit still for that long.)

The photos were so creamy and matte-surfaced that the portraits were often used as the basis for oil paintings, created by an in-residence Bachrach artist. The brothers sought for and achieved a “smooth, idealized look, as if the subjects had been sculpted out of cream cheese,” wrote Squiers.

Fabian had learned from classic European portrait painters—Frans Hals, Joshua Reynolds, Anthony van Dyke, James McNeill Whistler, and his favorite, John Singer Sargent. After all, their subjects were drawn from the same niche of society, except that royalty painted by the Old Masters were replaced by rich socialites, striving businessmen, and heads of state.

The Bachrachs also actively pursued clients by poring through wedding announcements, bridal shops, and Bonwit Teller’s bridal registry. They actively went after the debutante trade, via advertisements in The New Yorker and The Wall Street Journal. In one 1950 advertisement featuring a model used by Avedon, they discreetly bragged, “When a top fashion model such as Dovima wants photographs for her personal use, she goes to Bachrach.” Another ad purred, “This year the loveliest brides will be photographed by Bradford Bachrach.”

Perhaps the most famous of their bridal portraits is Jacqueline Kennedy’s—her solemn doe eyes framed by delicate, cascading lace—though many brides included in the Bachrach catalogue are now unidentified, caught for posterity in their ivory-and-cream beauty.

The brothers sought for and achieved a “smooth, idealized look, as if the subjects had been sculpted out of cream cheese.”

The Bachrachs knew exactly what people wanted from a portrait. “I do not believe,” Fabian once noted, “that the average person wants a ‘map’ of his face—I believe he wants to be idealized.”

With clever lighting and the proper backdrop and pose, the Bachrachs could make weak jawlines look firm, droopy eyes look commanding, slack mouths look resolute, obese men look robust. For women, “Dietrich lighting” was often employed, named after Josef von Sternberg’s way of lighting Marlene Dietrich from above (also known as “the butterfly effect,” as it projected the shape of a butterfly under the nose). In a formal portrait taken long before his presidency, Donald Trump was spotlighted to make his blond hair shine like a Breck girl’s. Unfortunately, as Squiers noted, the image “has the faintly gilt-edged air of a debutante.”

Bachrachus Americanus

Fabian entered his final darkroom in February 2010 at the age of 92. By then, his two sons, Robert and Louis “Chip” Fabian, were grown men with families. Though Chip, a rambunctious youth, had served his father in the studio since his early teens, he wasn’t all that interested in taking up the family business. Robert was more eager, starting by working summers in the studio, learning the Bachrach style and mixing chemicals in the lab.

Chip and Robert took over in the 1970s just as a great cultural shift was underfoot. The idea of the family portrait was changing, as was the idea of family itself. Mod and hippie-style fashions were replacing the man in the gray flannel suit and the coiffured debutante. People were marrying barefoot on the beach, so the formal Bachrach style suddenly seemed as hokey as a Norman Rockwell painting—a diorama of a nearly extinct species, the Bachrachus Americanus.

As business slowed down, the brothers began to feud. What began as a friendly competition for clients led eventually to the shuttering of Bachrach Studios. The longest family-run photography business came to a close in 2009.

The following guidelines were created by Fabian during Bachrach Studios’ golden era:

The pretty woman should be made to look interesting and intelligent.

The plain woman should be given an air of beauty and glamour.

The older woman needs distinction and an air of experience.

The shallow woman should have an air of mystery.

The young man should be made to look more grown up.

The short man needs dignity and greater height.

The rough-looking man needs an air of breeding.

The pretty man needs a look of rugged masculinity.

Every man must seem to be graceful, strong and virile.

Every woman must be charming, graceful, have distinction, and aristocratic bearing.

They not only defined the Bachrach ideal, but now serve as the portrait of a vanished age.

Sam Kashner is a Writer at Large for Air Mail