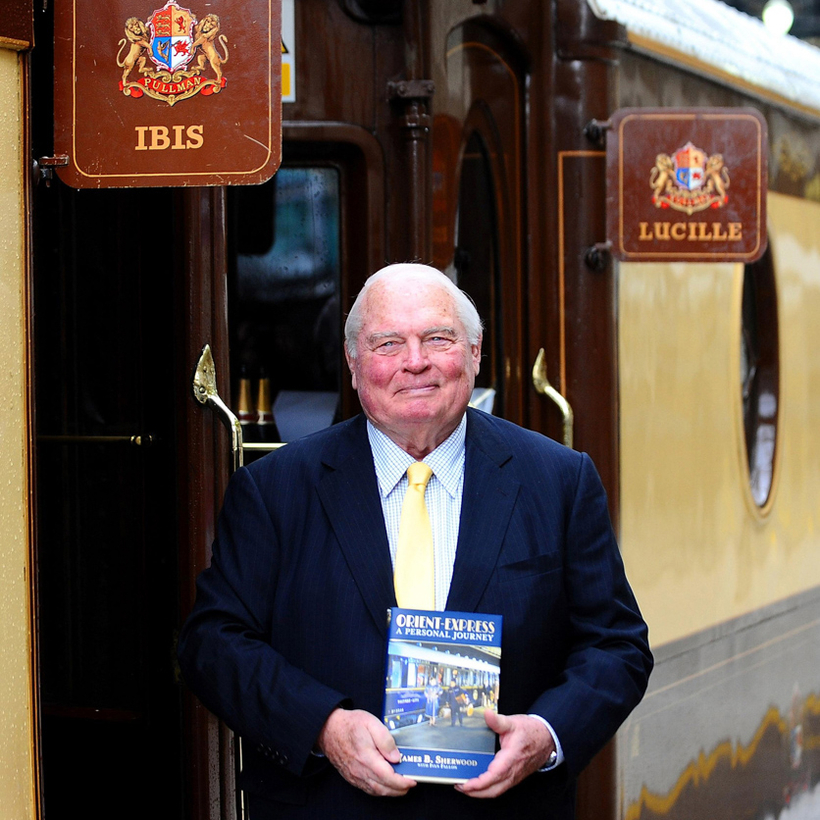

In October 1977 Jim Sherwood bought two shabby prewar sleeping carriages at a Sotheby’s sale held in a freight yard of Monte Carlo’s railway station. They were not any old carriages, however: they were all that remained of the fabled 1920s Orient Express train and had featured in the film Murder on the Orient Express. He paid $72,800 for the first one and $41,000 for the second.

Sherwood’s plan was to use them to recreate the Orient Express train and operate it between Paris and Venice, where he had bought the Cipriani hotel the year before. He had budgeted $5 million for the project that he reckoned would take two years; in fact it cost $30 million and took five years.