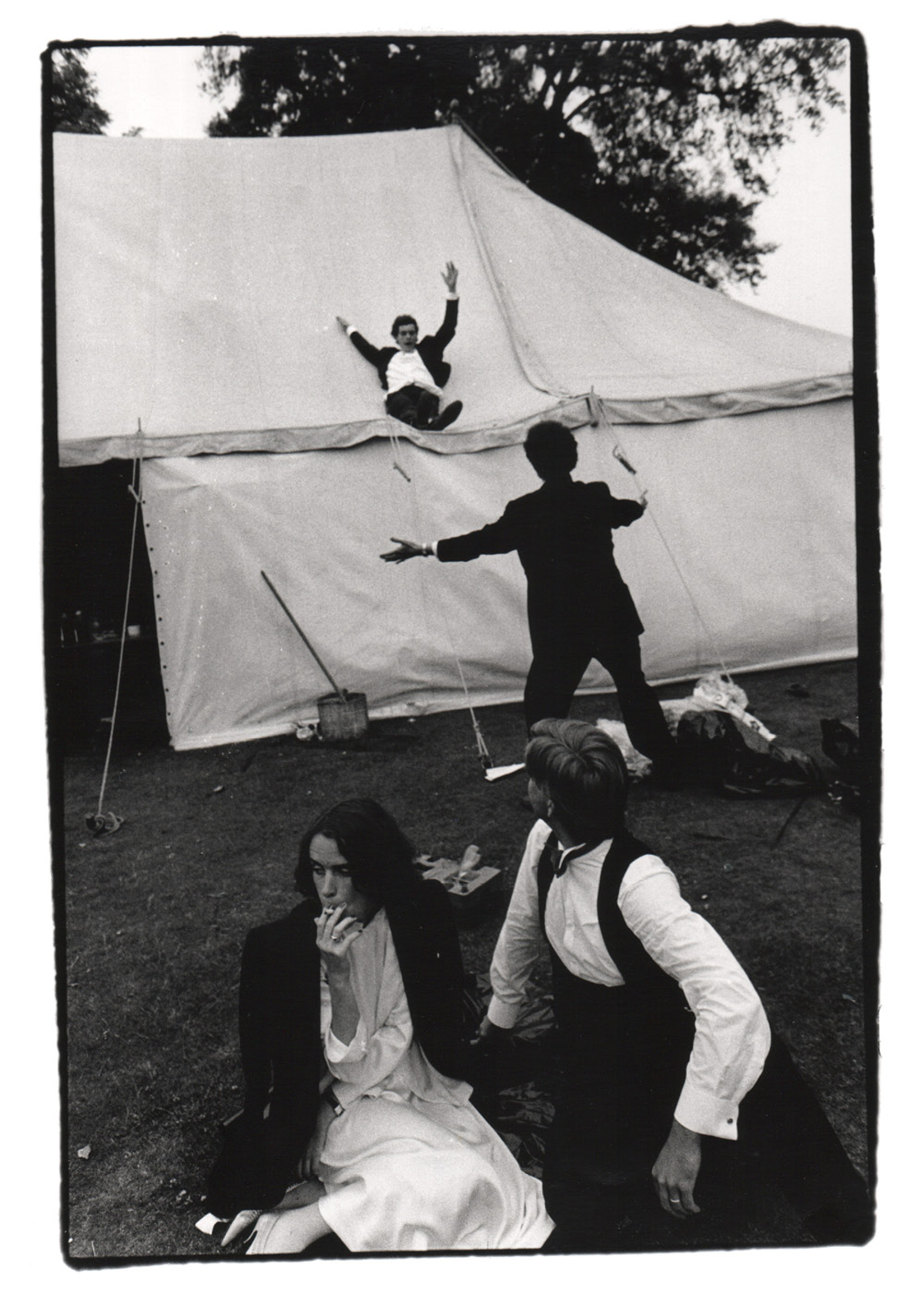

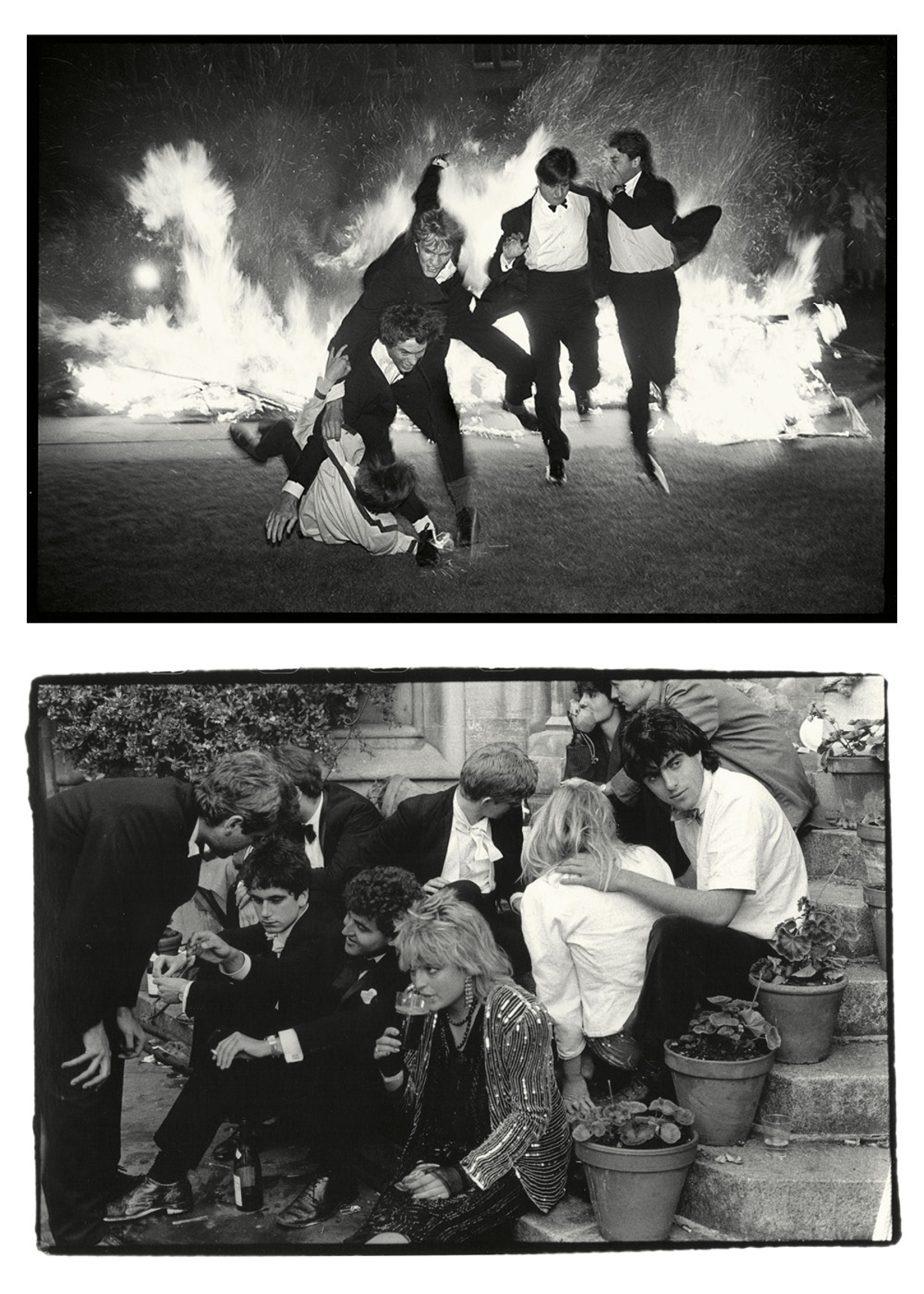

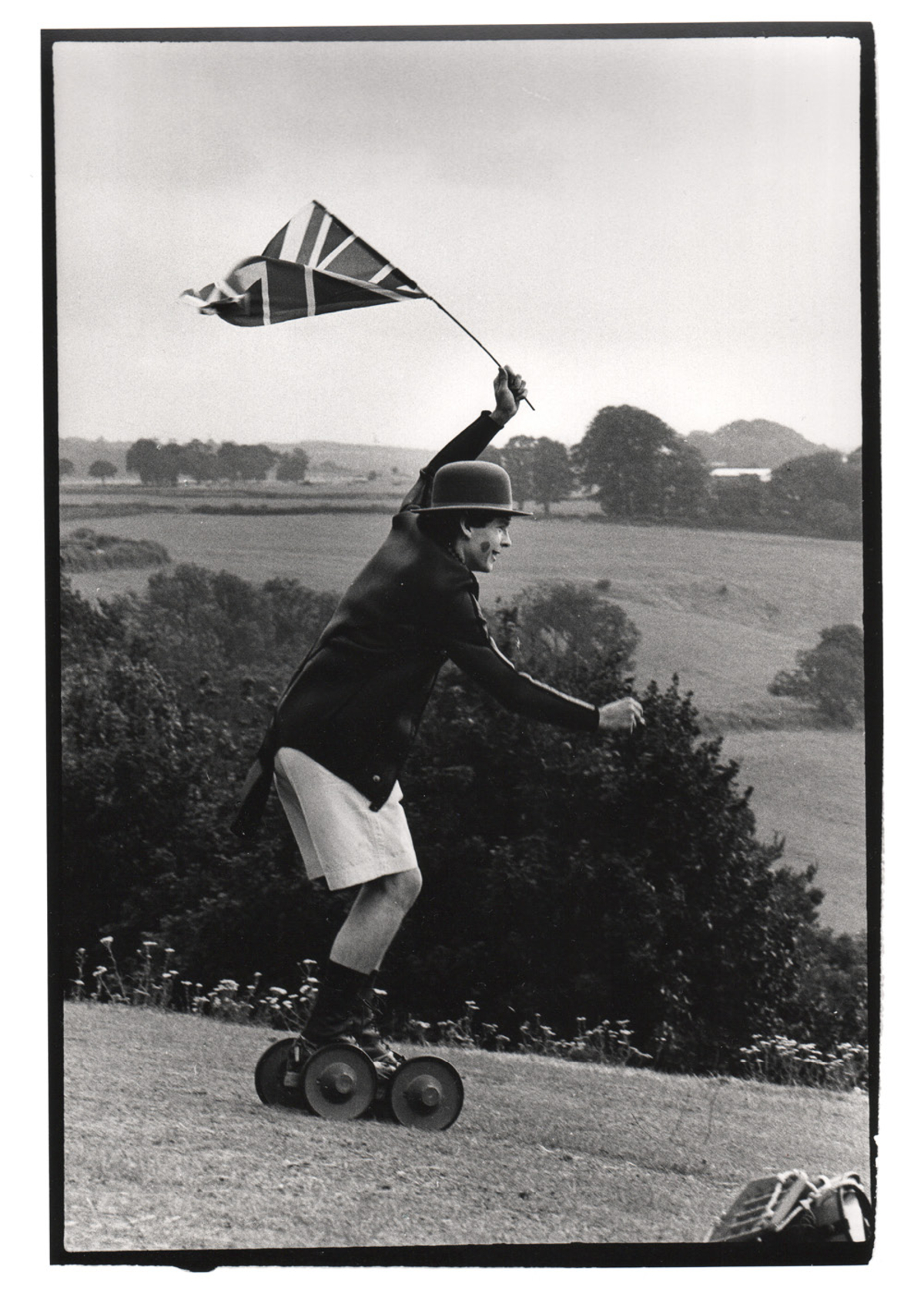

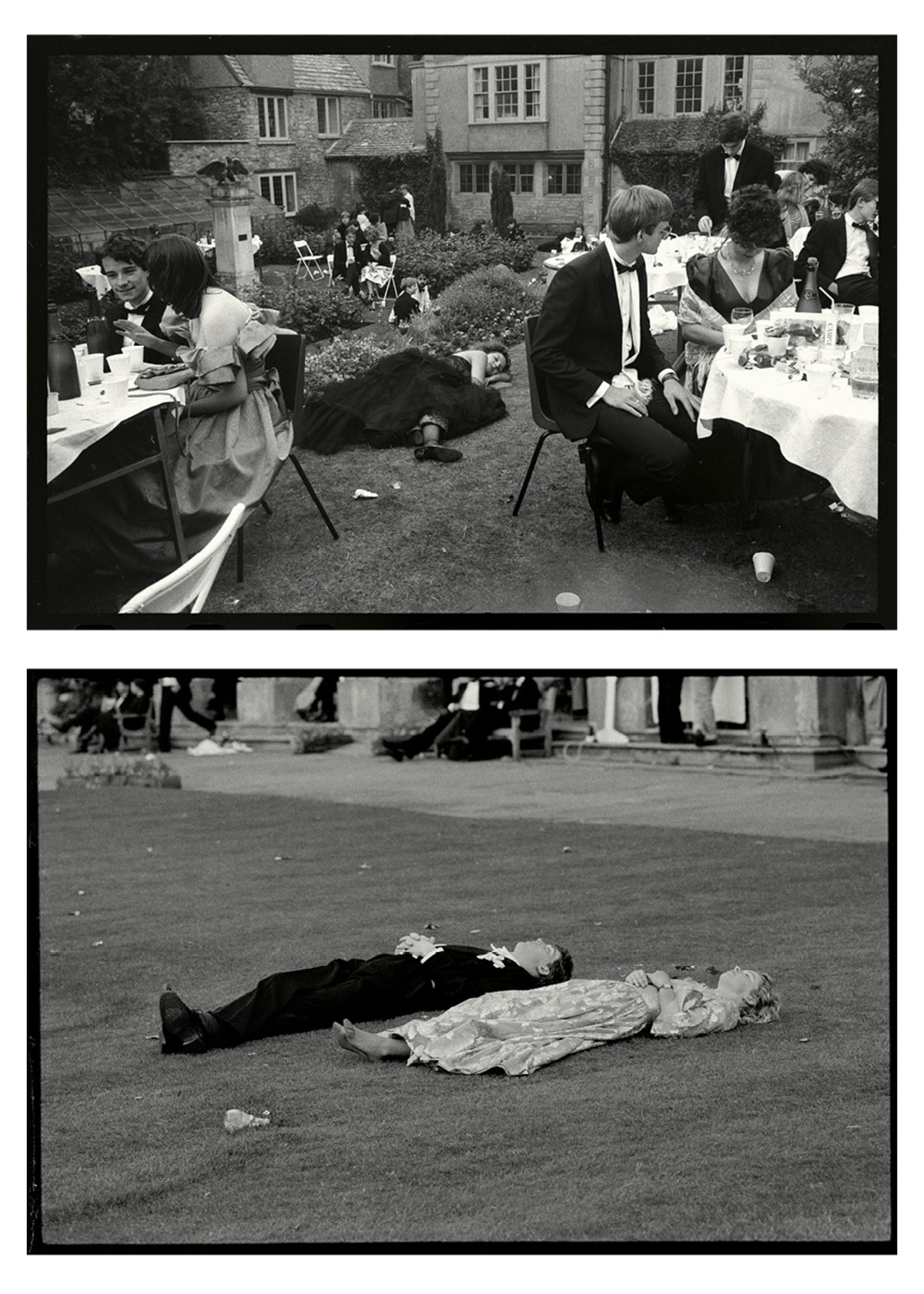

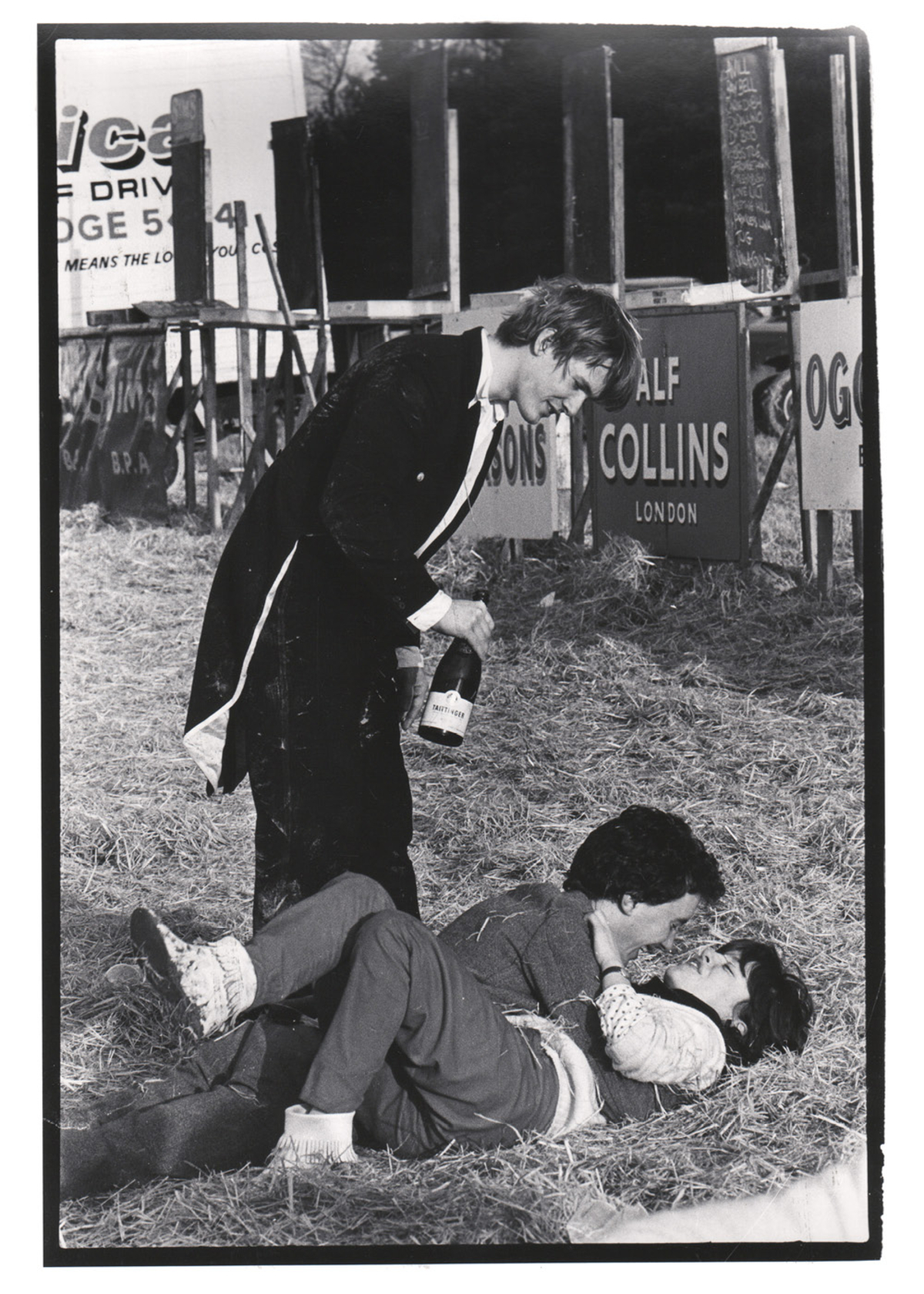

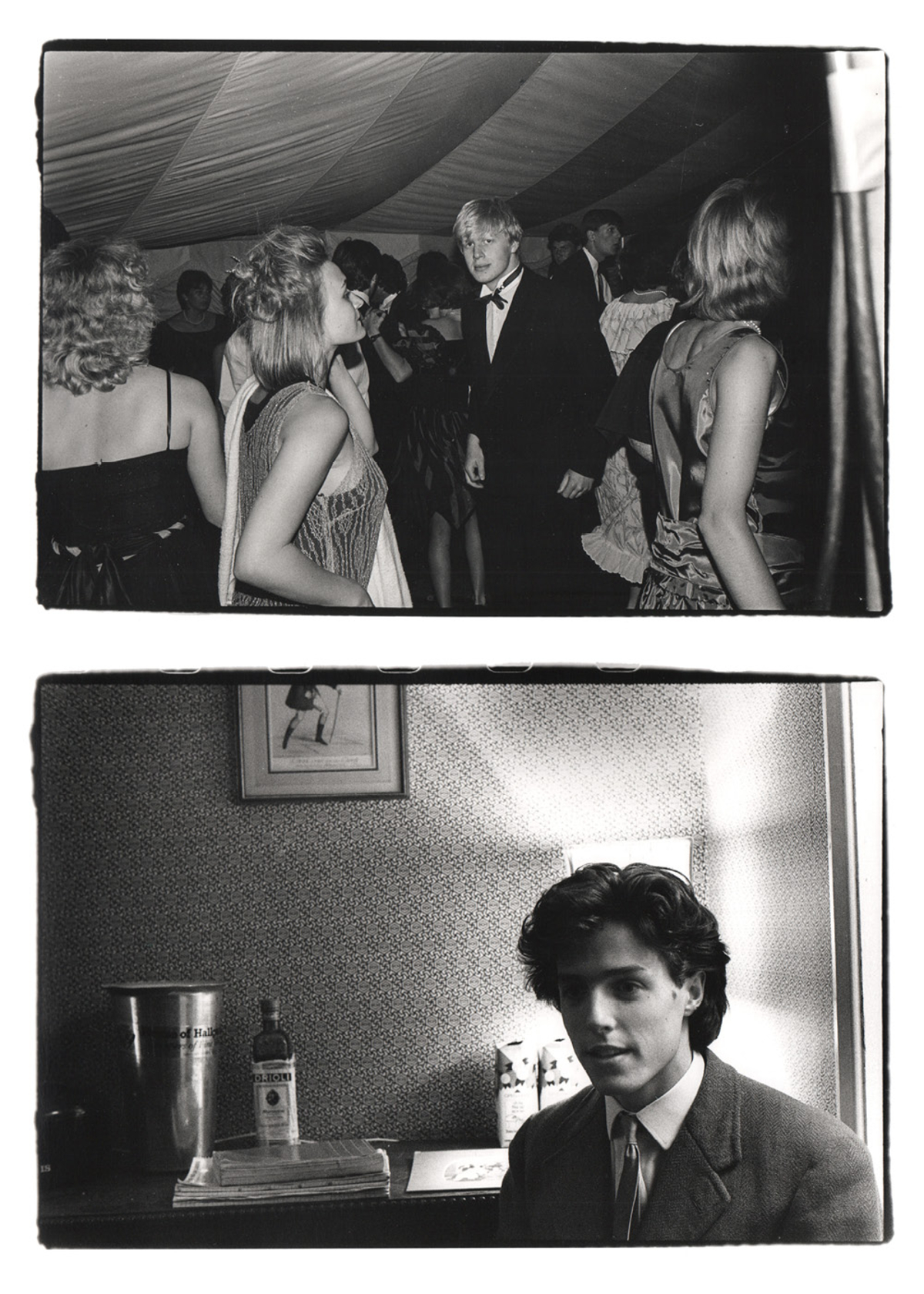

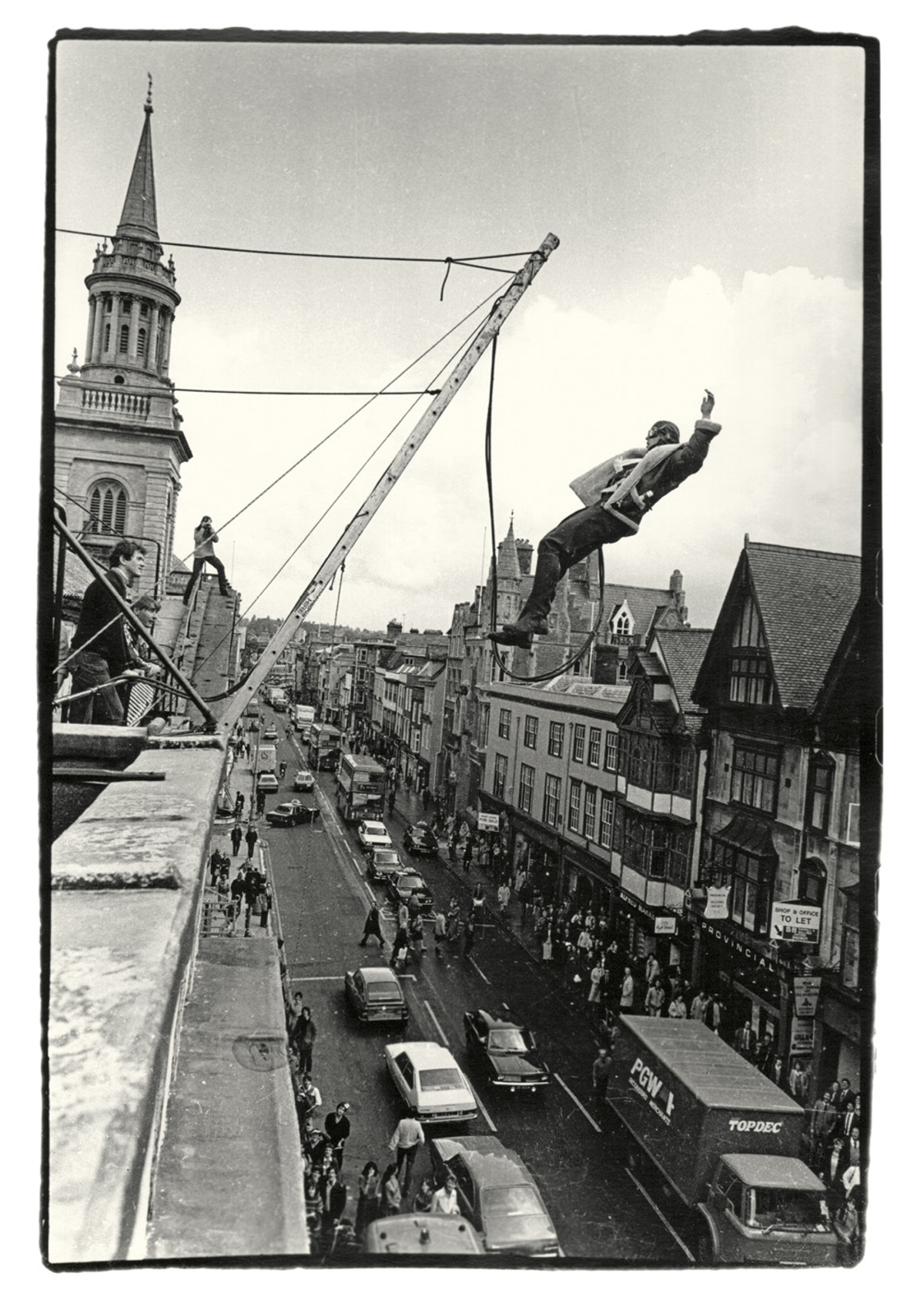

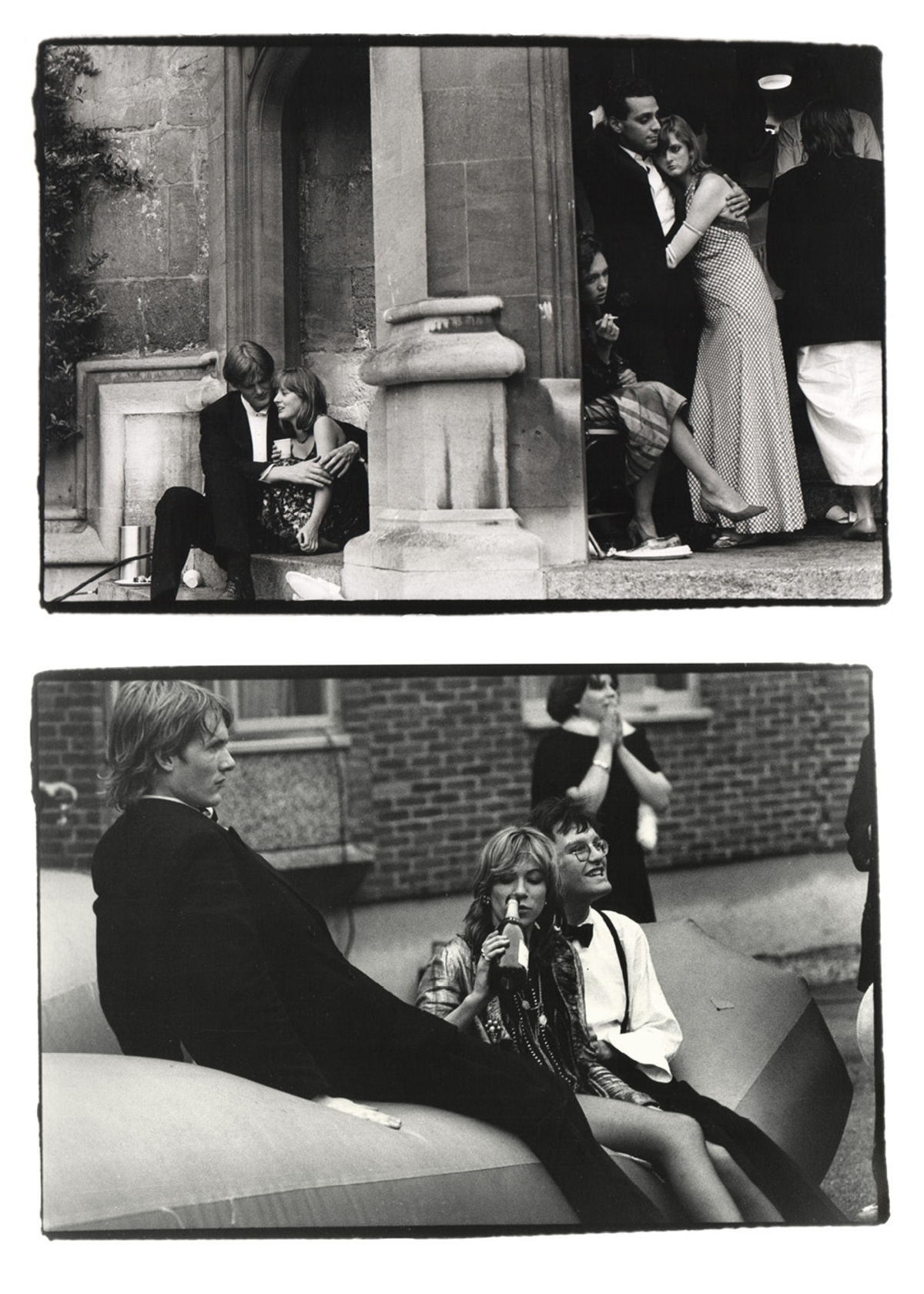

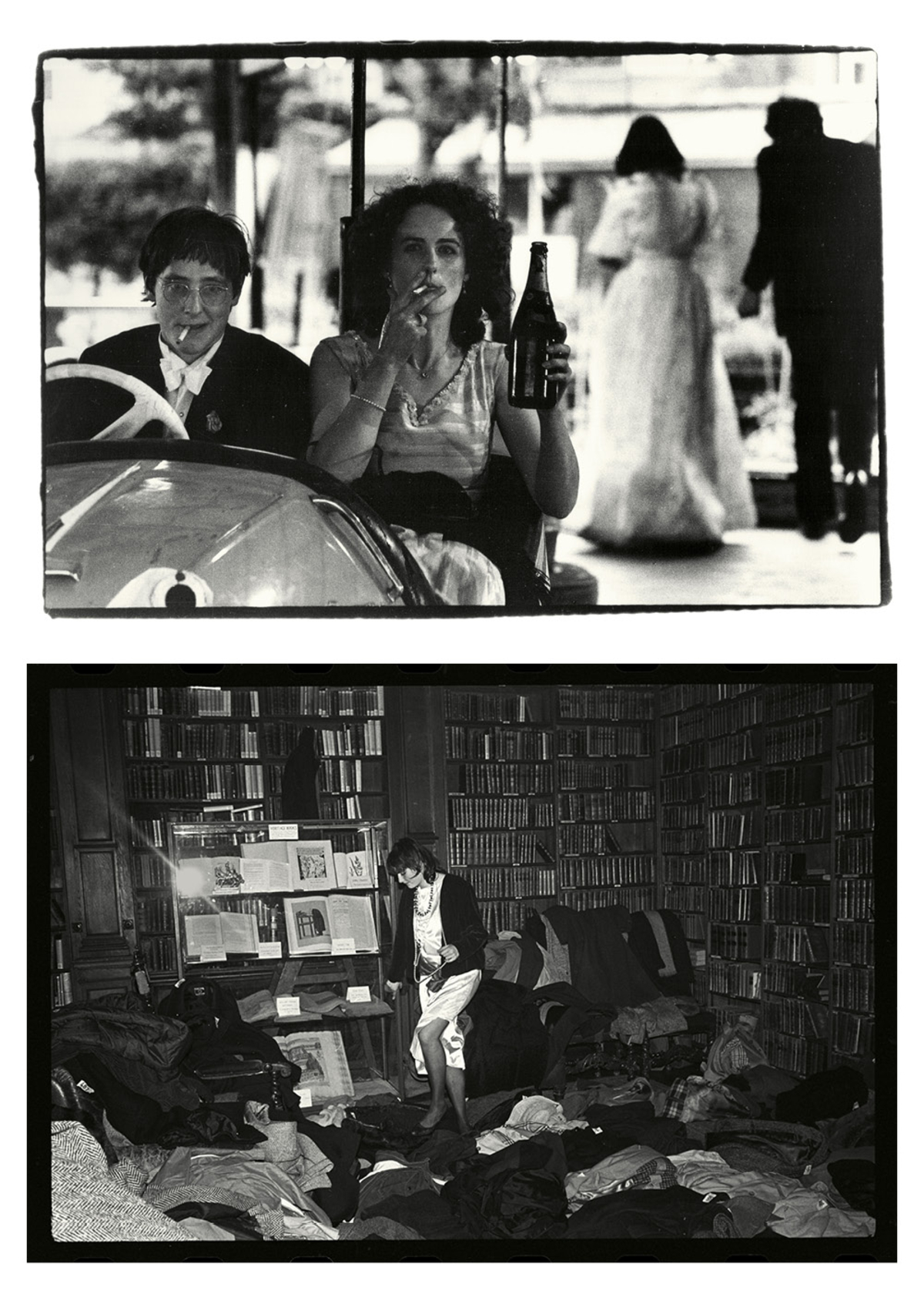

I’ve spent the last few months looking through my films from Oxford, taken between 1976 and 1988, and deciding which ones to include in a new book. I had originally thought I had 25 or so decent pictures from that time; I was surprised to find quite so many.

I lived in Oxford starting from the age of 10, when my family moved there from Wales, but I was never a student at Oxford University. I was a state-school pupil at Oxford Grammar School. But it was chaos there. With hindsight, it is obvious that the headmaster, a World War II R.A.F. veteran, was suffering from wartime traumas. He would bang his head against the wall and shout about going into a “flap spin.” In any case, he saw me as a troublemaker. I left after O levels, in the early 1970s.