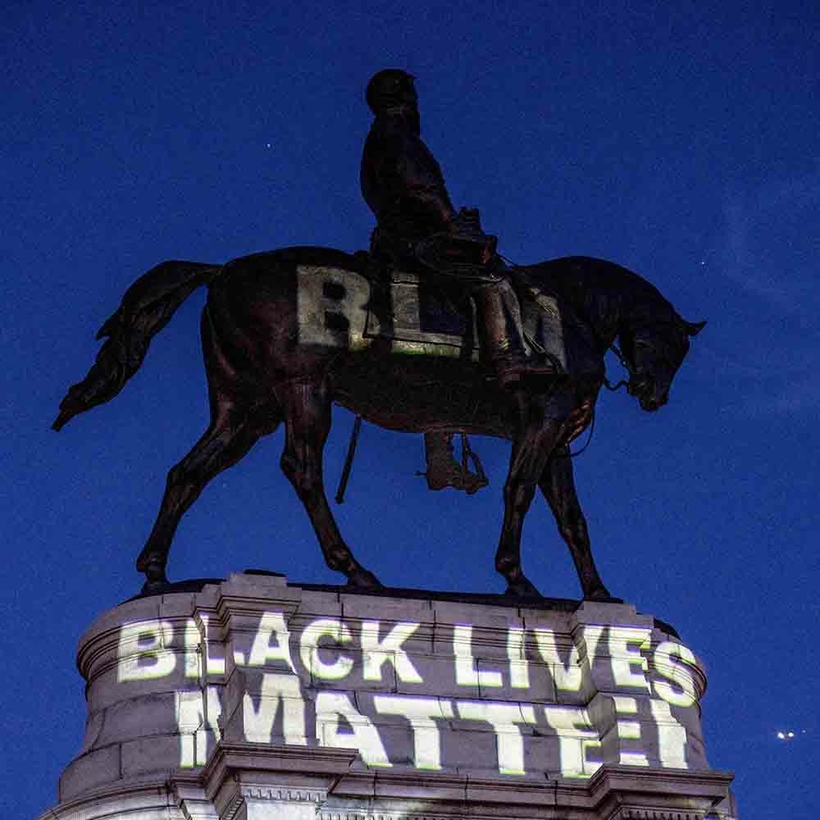

Here is a simple, long-standing principle of war. If you want statues of your heroes displayed in public squares and you wish to see the flag of your country snapping brightly in the breeze, you have to win the war.

We don’t have statues of King George III or Saddam Hussein. We don’t train our future heroes at Fort Hirohito. You lose the war, you lose the statues and the flags and nobody names a military base after you. Except if you’re the South and you lost the Civil War.