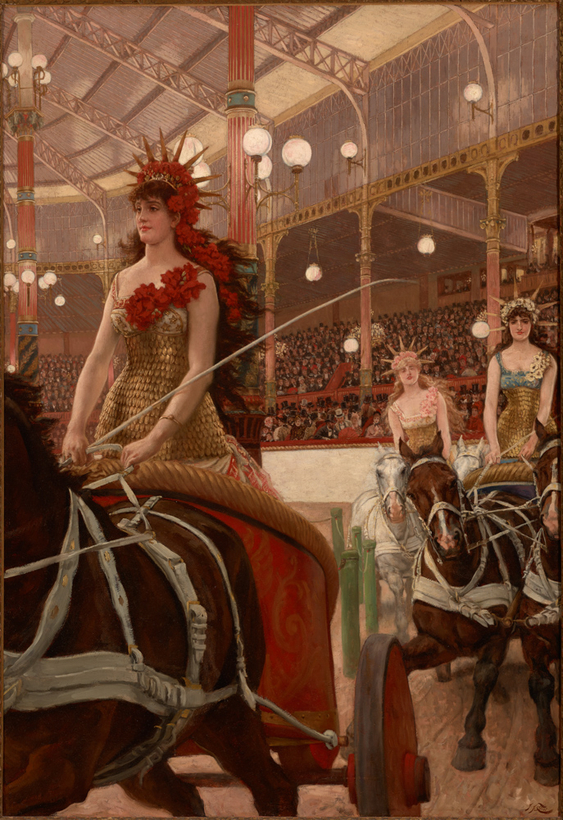

Jacques Joseph Tissot, born in Nantes in 1836, was an Anglophile who went by “James” and moved to London in 1871. He made tender portraits of his Irish lover, Kathleen Newton, until she died of tuberculosis. Back in France, he painted confident Frenchwomen in lively crowds and sensuously cinched dresses, but Parisians dismissed the subjects as too British. He illustrated anguished scenes from the Bible in precisely composed tableaux en gouaches, led by his re-discovered Catholic faith. It can be confounding to try to bind it all together. How do you catch a cloud and pin it down?

In the first Paris retrospective dedicated to Tissot since an exhibition at the Petit Palais in 1985, the curators at the Musée d’Orsay take on the painter’s legacy with a title that confronts his malleable reputation. What makes Tissot, or his modernity, ambiguous? According to Marine Kisiel, one of the show’s curators, “His ability to draw from many sources gave the image of a versatile artist, who could successively—and simultaneously sometimes!—borrow inspiration from ‘archaic’ forms of art (medieval art, Japan, and even Pre-Raphaelitism) as well as develop a very modern art. In the 1860s, he participated in the emergence of modernity in painting, alongside Whistler and Manet, for example. As such, he was considered a plagiarist by some, but our aim is to show how adaptable and shrewd he proved to be.”