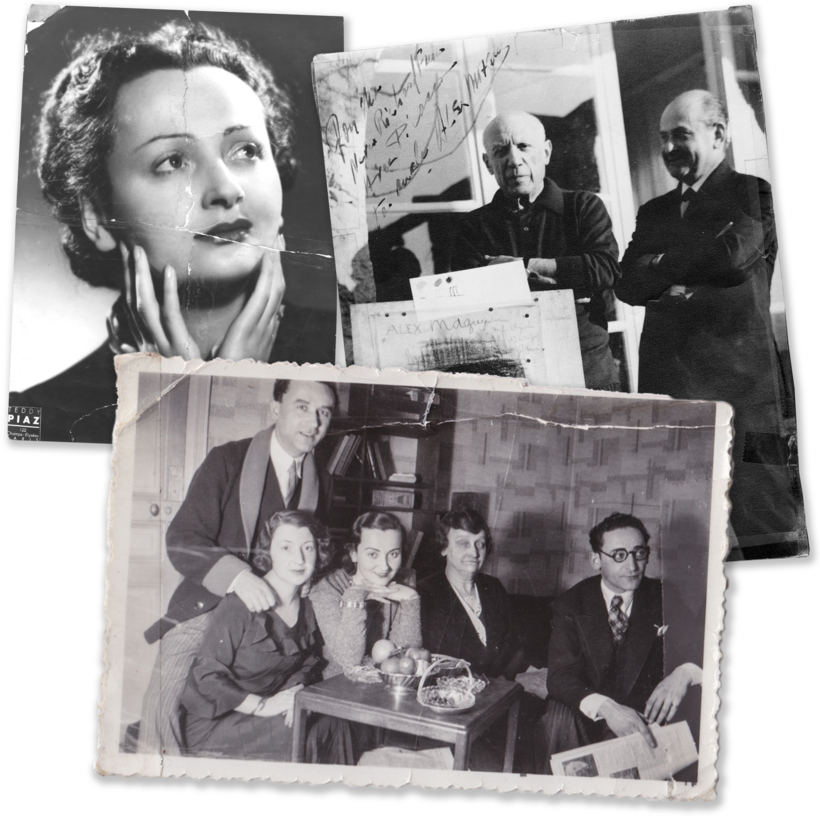

That my great-uncle, Alex Maguy, had led a glamorous life was not news to me. Even as a sulky teenager, determinedly unimpressed by everything, I could hardly miss the clues when I would go round to his apartment in Paris, a jewel of a home on the Avenue Foch, still one of the ritzier streets in the city. There we would be, having lunch in his dining room, food brought to the table by a liveried waiter, and hanging on one wall was a Monet; on another, a Van Gogh. If I had to go to the bathroom, I’d walk past several Picassos, and there, hanging above the toilet, almost as an afterthought, was a Matisse, personally inscribed to him.

So, when I started to research Alex’s life, in 2001, two years after he died, it was not a revelation to find photos of him in old French society magazines, always pictured with the fabulous people of the day: Maurice Chevalier, Yves Montand, Ava Gardner. He even makes an appearance in Richard Burton’s diaries, with Burton describing how he and Elizabeth Taylor went to Alex’s art gallery, in Paris, and then to his apartment to admire his personal art collection, even more impressive than the art he showed to the public. All this was pretty much what I expected. What surprised me was realizing how much Alex’s life has influenced my family today.

Paris-Bound

Alex aside, my family is not very glamorous, and that’s because glamour and fanciness have long been considered dangerous. My grandmother and her three brothers were not actually French at all but Polish. They grew up in a small shtetl called Chrzanów, just a handful of miles from Auschwitz. They were forced to flee in the early 1920s to escape the pogroms that tore through the town at the end of World War I. Yet these pogroms ended up saving their lives: if they hadn’t been driven out of Chrzanów, they would almost certainly have died during the Second World War.

The four siblings fled to Paris, where their cousins, the Ornsteins, were waiting for them. They fell instantly in love with the city. The beauty of the buildings, the elegance of the people, the stylishness of the fashions: it all stood in stark contrast with the grim poverty they’d left behind in Poland, and they made themselves over as French. They jettisoned their Polish names—Jehuda, Jakob, Sender, and Sala Glahs—for the French ones I came to know them by: Henri, Jacques, Alex, and Sara Glass. Henri and Sara, in particular, dressed in emphatically French styles, and Alex worked as a couturier, making the most-French fashions for fellow Francophiles in the U.S. and U.K.

But W.W. II did not spare them: Jacques was killed in Auschwitz, and my grandmother ended up in America, married to a man she barely knew, in order to escape the Nazis. After the war, Henri and Alex, who had managed to stay in Paris, became very wealthy, Henri from engineering and Alex from art collecting. Even my grandmother was comfortable on Long Island. Henri and Sara loved elegance and style, but they would never have considered buying anything flashy, anything that might draw attention to them, because they never really recovered from the shock of France’s turning on them during the war.

They jettisoned their Polish names for the French ones I knew them by: Henri, Jacques, Alex, and Sara Glass.

Alex lived differently. He made sure to befriend the powerful and famous—Georges Pompidou, I. M. Pei, Pablo Picasso. Perhaps his most enduring friendship throughout his life in Paris was with Christian Dior. Alex met Dior when the former was working as a couturier in the 1930s and the latter was a struggling draftsman. Dior, along with René Gruau, worked for Alex’s fashion label, drawing the sketches for his designs. During the war, both Alex and Dior were in the South of France and would share civilian clothes, as they were about the same size (short, in other words). Afterward, they opened their couture salons around the corner from each other in Paris, where Dior launched his famous New Look collection in 1947. When Alex switched to art and opened a gallery, Dior attended the parties he hosted there.

I hadn’t known about any of this until I happened to find Alex’s unpublished memoir, left among my grandmother’s belongings. After the Glass siblings died, the extended family drifted apart. I barely knew the names of my French cousins, let alone their professions. It was through fashion, which I pursued after university, that I met my Ornstein cousins. Then one day at a Dior show in Paris, a handsome man approached me. “I think you’re my cousin?” he said. It was Alex de Betak, the grandson of Henri Glass, and a fashion-show producer in Paris. While de Betak works for some of the biggest names in the business, from Nike to Saint Laurent, his longest-lasting relationship is with Dior.

Alex’s friendship with Dior came as much as a surprise to de Betak as it did to me. But the past holds on to you in ways that coincidence sometimes can’t explain, and sometimes it can bring a fractured family back together again.

Hadley Freeman’s House of Glass: The Story and Secrets of a Twentieth-Century Jewish Family is out now from Simon & Schuster