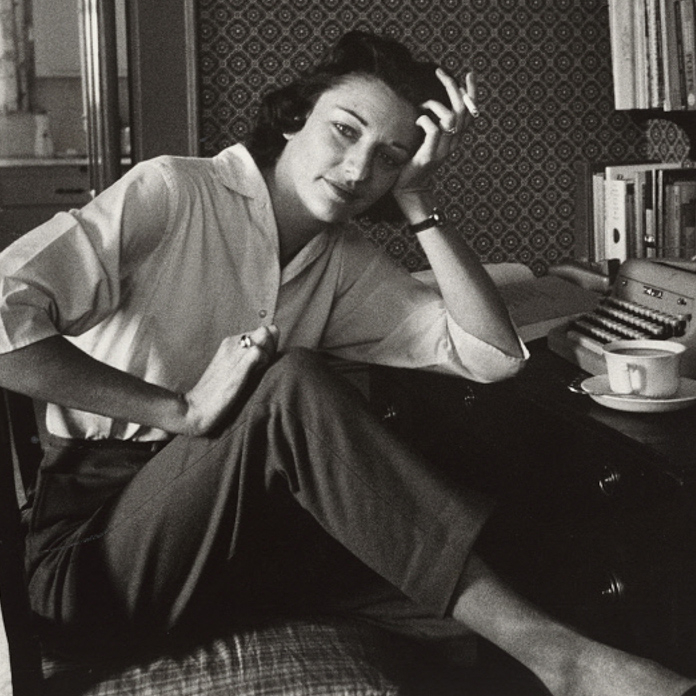

“What kills the creative instinct—what blunts the axe?” When the poet Anne Sexton—singularly gifted, beautiful, tortured—posed the question, she was giving voice to the many talented, disaffected women of her time. Hers was a questing that implicitly demanded not just an answer but a cure. In 1960, that cure was the Radcliffe Institute for Independent Study, the first of its kind anywhere in the country, a place where a woman could “simply be a mind among other minds.” It was also a liberation unlike anything before it in academia.

For nearly 40 years, from 1960 to 1999, poets, novelists, painters, sculptors, scientists, lawyers, philosophers, and playwrights found a receptive environment for study at Radcliffe. Here women such as Denise Levertov, Nan Rosenthal, and Anna Deavere Smith became resident scholars, each having a room of her own for a full year, along with a cash fellowship, to encourage and enable creativity. As Maggie Doherty, professor of English at Harvard University, writes in her new book, The Equivalents, “What had started as a ‘messy experiment’ with twenty-four mostly local women had become an established institution of national renown.”