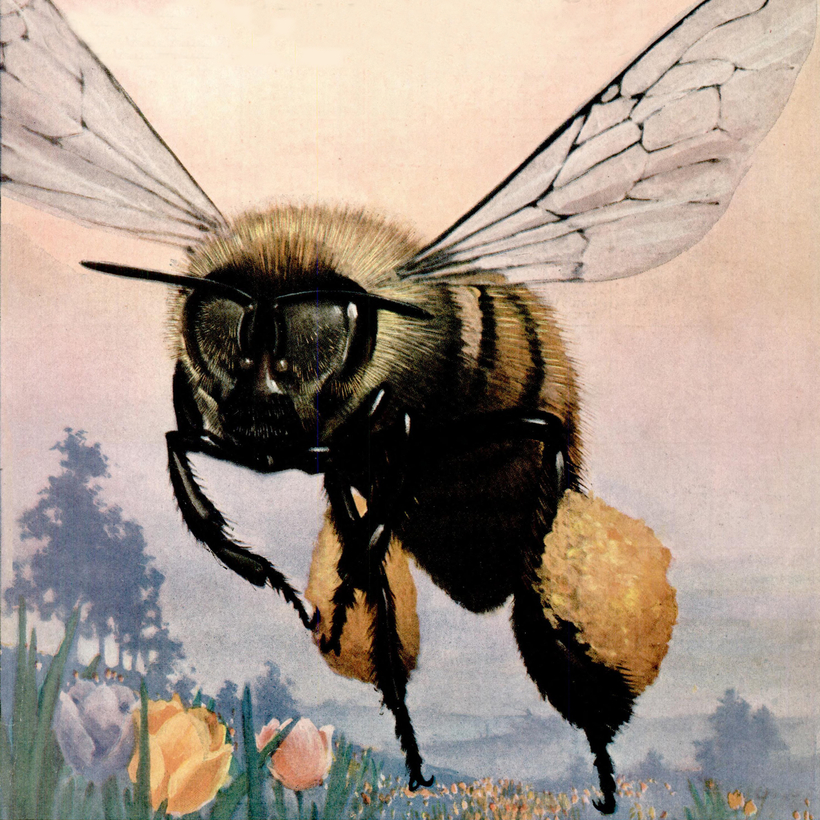

Bees may be famously hard workers but a study suggests that as they forage for food they rely not only on industry but a clever gardening technique.

Researchers have found that during times when pollen, their sole source of protein, is in short supply, bumblebees will nibble the leaves of flowerless plants.