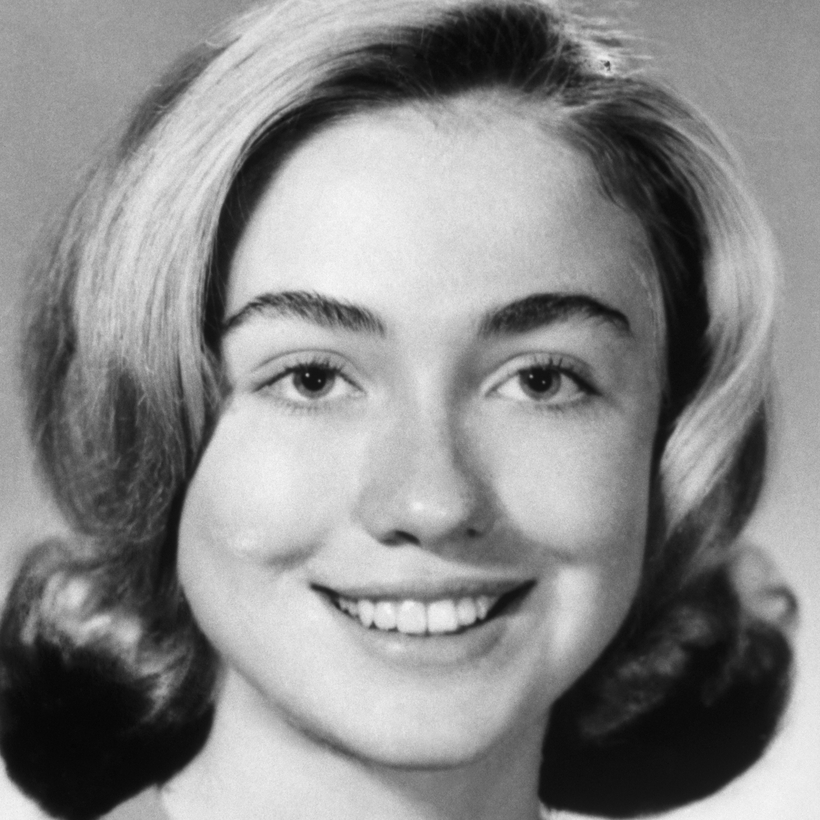

The novelist Curtis Sittenfeld has written the autobiography of the woman who would have been Hillary Rodham — if she hadn’t married Bill Clinton. It’s detailed and well researched, but the first half is only true in parts; the second half is almost all false. And the intimate details of her relationship with Bill are fictional — the moment she grasps his white buttocks, for example, is entirely unsubstantiated.

“I have complicated feelings”, Sittenfeld says, “about the sex I chose to include. And I feel it makes the story.”