Manhattan private-school parents have a well-deserved reputation for letting nothing get in the way of what they think is best for their kids—especially when it comes to how a school is run. Still, you might think that in the chaotic early days of the coronavirus’s arrival in the city, even as schools struggled to close down to protect children, their parents might be able to put aside their self-interests and agendas.

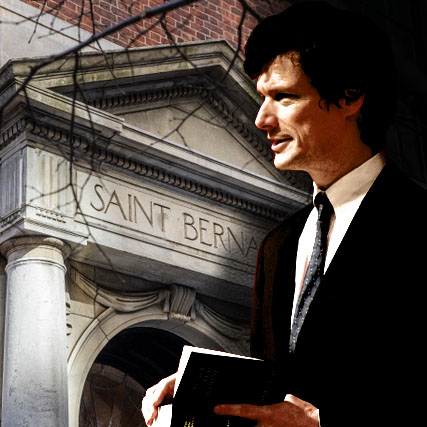

In most schools that was surely the case. But St. Bernard’s, on the city’s Upper East Side, is not most schools. And not even the arrival of a global pandemic was going to keep a months-long battle being fought at the school from escalating into a legal battle. On March 19, 2020, two anonymous parents (John Does 1 and 2) found the time and energy to file a civil lawsuit in New York State Supreme Court against the school and its executive committee. As Jim Walden, the attorney for the plaintiffs, said, “There is power and wealth on both sides of this drama.”