The letter to the editors of Mad magazine carried an air of imperious menace worthy of Darth Vader himself.

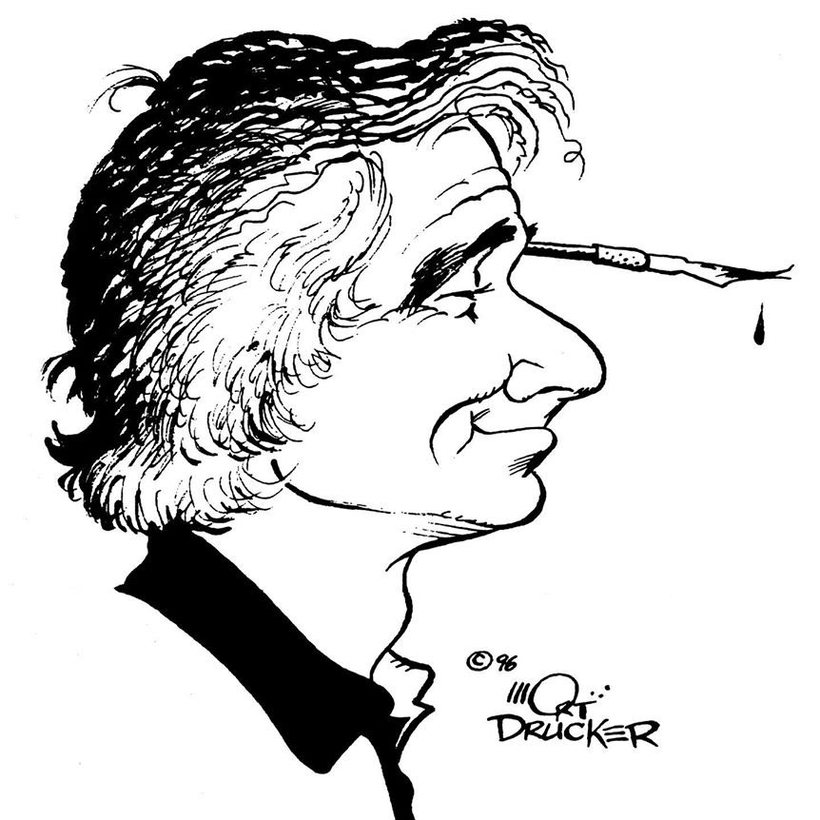

The humorous American publication lampooned the second Star Wars movie, The Empire Strikes Back, with a cover image of the Mad mascot, a freckled, gap-toothed child named Alfred E Neuman, as Yoda. Inside, a cartoon by Mort Drucker, titled “The Farce Be With You”, mocked characters such as “Princess Laidup”, “Ham Yoyo” and “Lube Skystalker”.