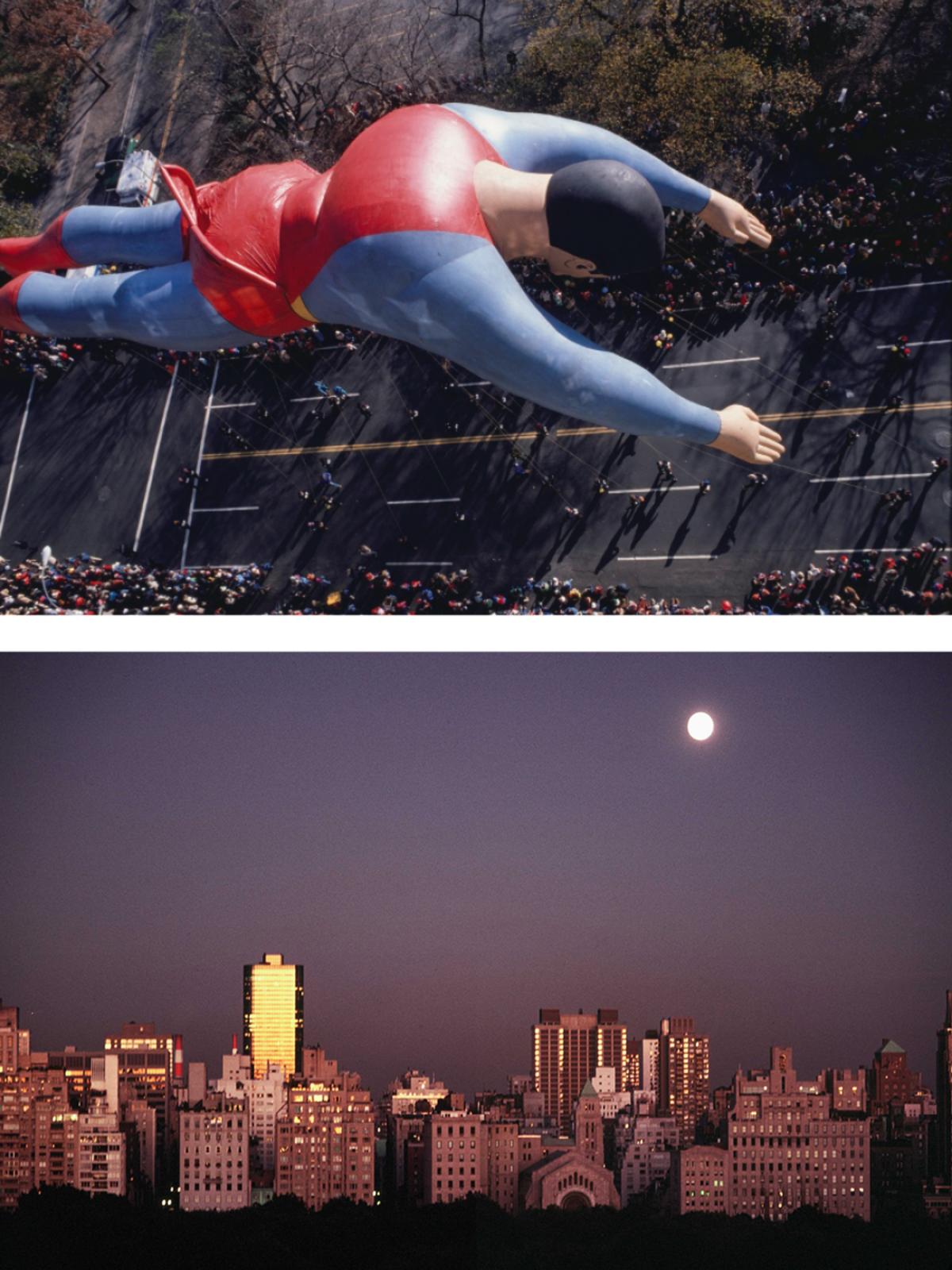

My window shows the travelling clouds,

Leaves spent, new seasons, alter’d sky,

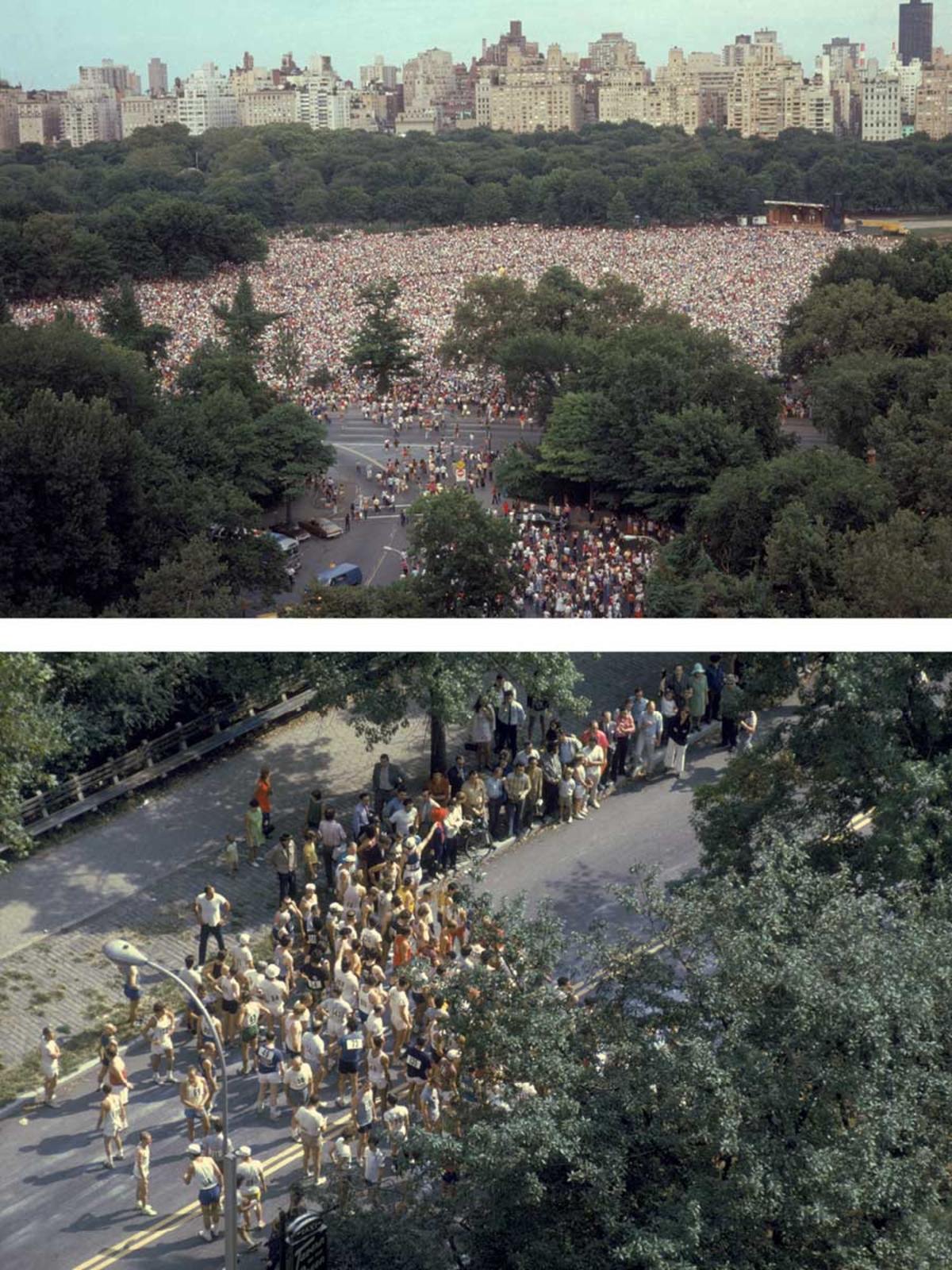

The making and the melting crowds:

The whole world passes; I stand by.

—Gerard Manley Hopkins

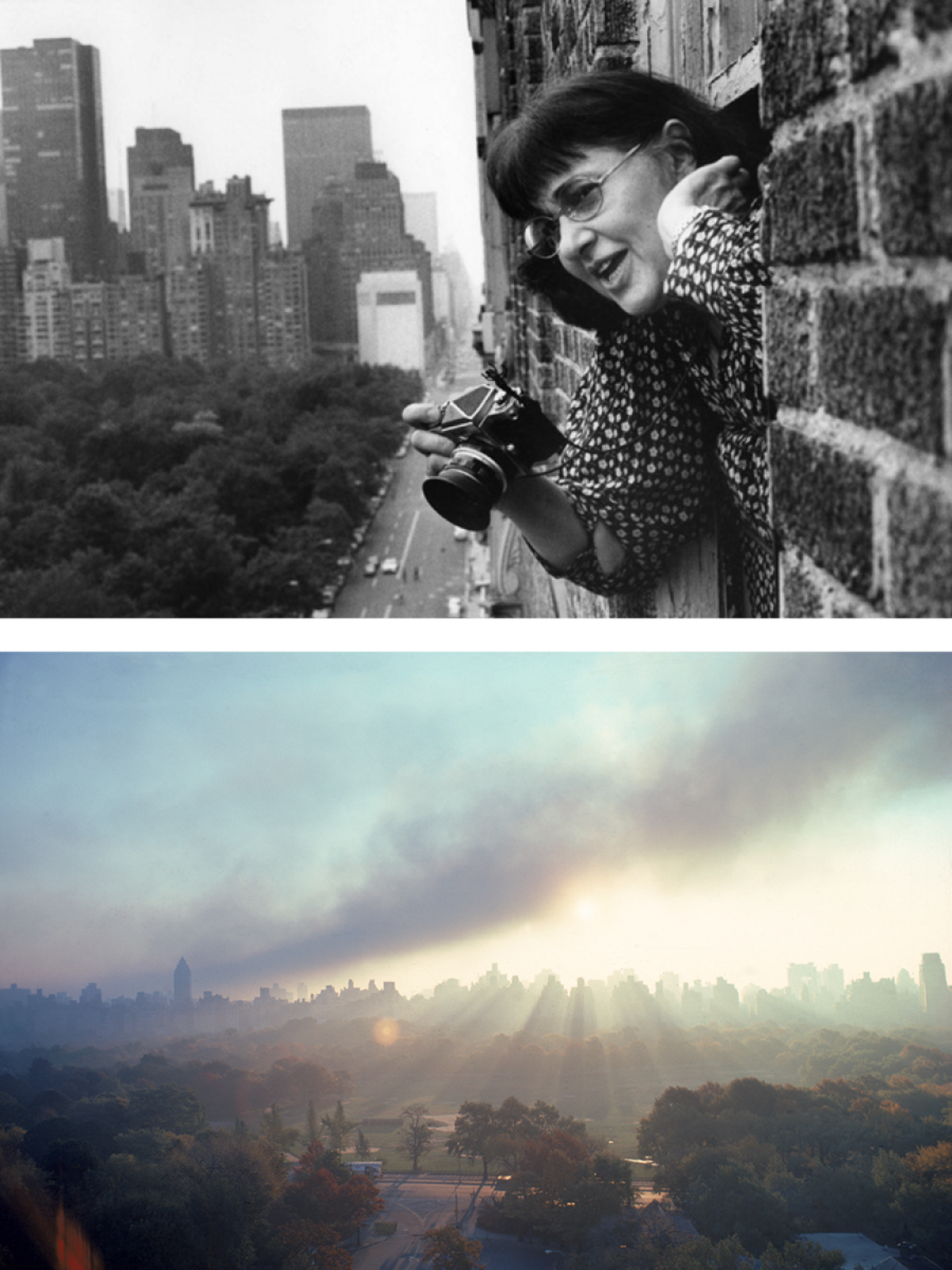

Mostly she waited. Waited “for the clouds to become the right shape,” for a shadow or a ray of light, sometimes rising before dawn to shoot a sunrise that “I must have sensed in my sleep.”