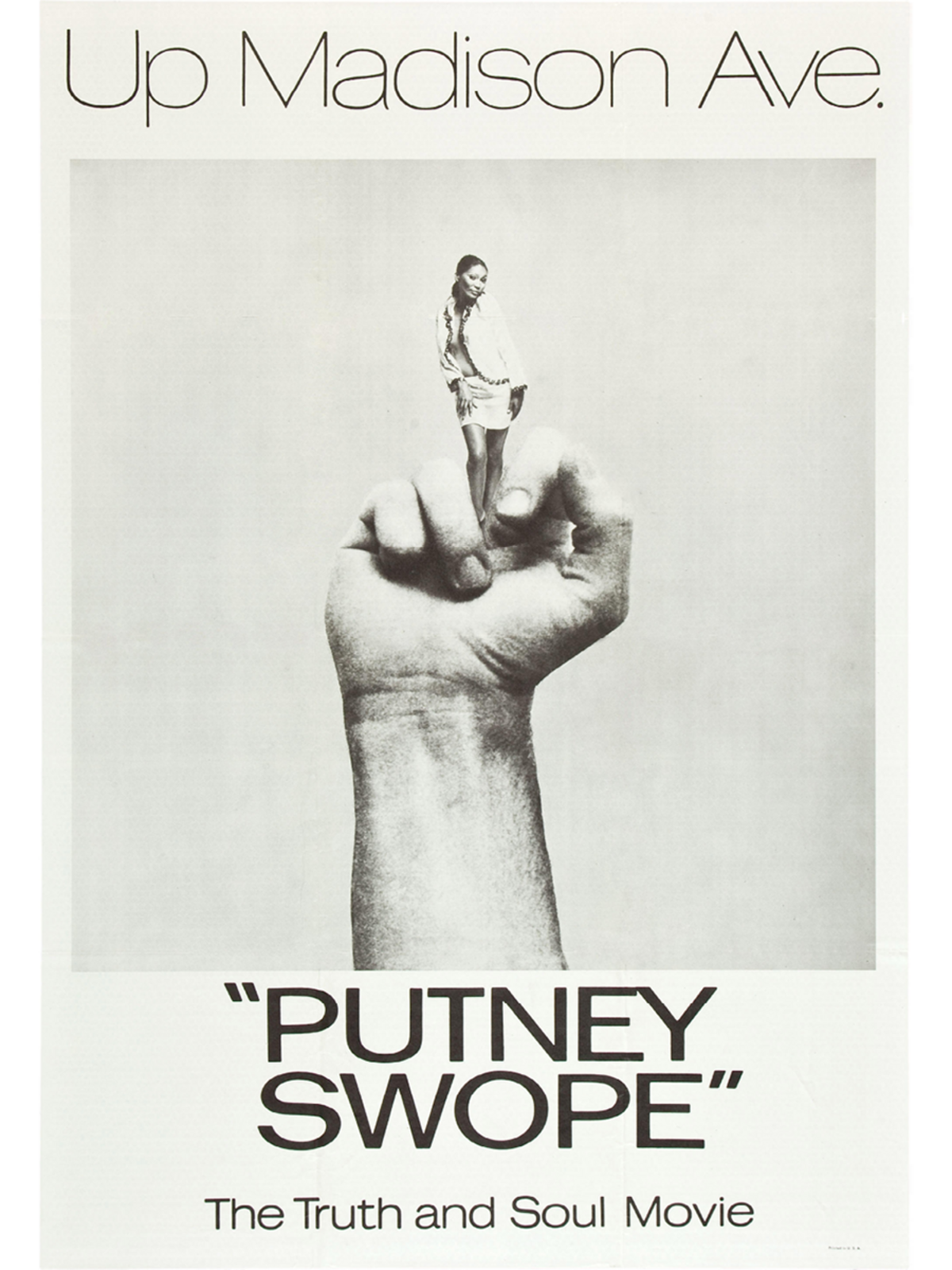

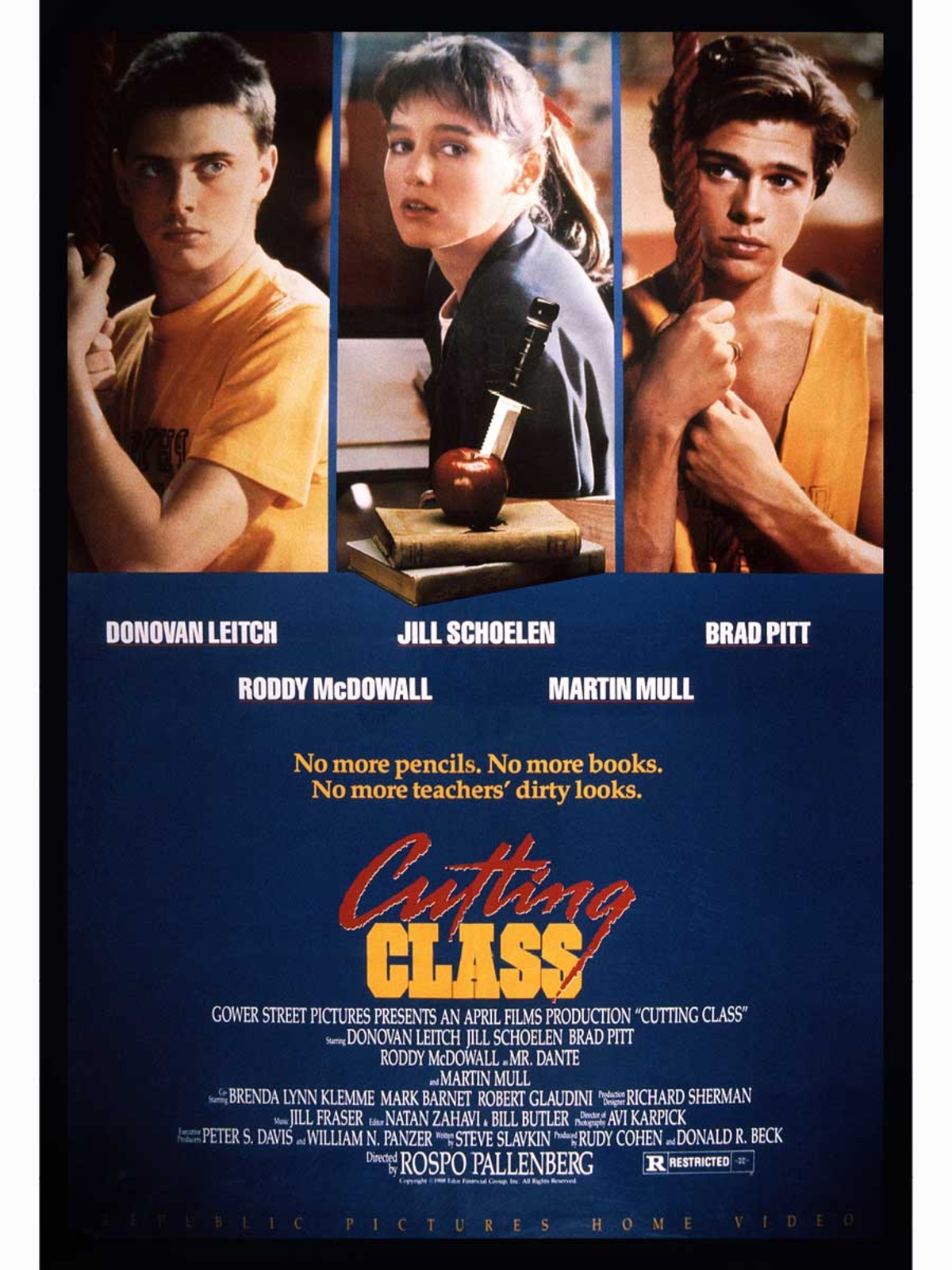

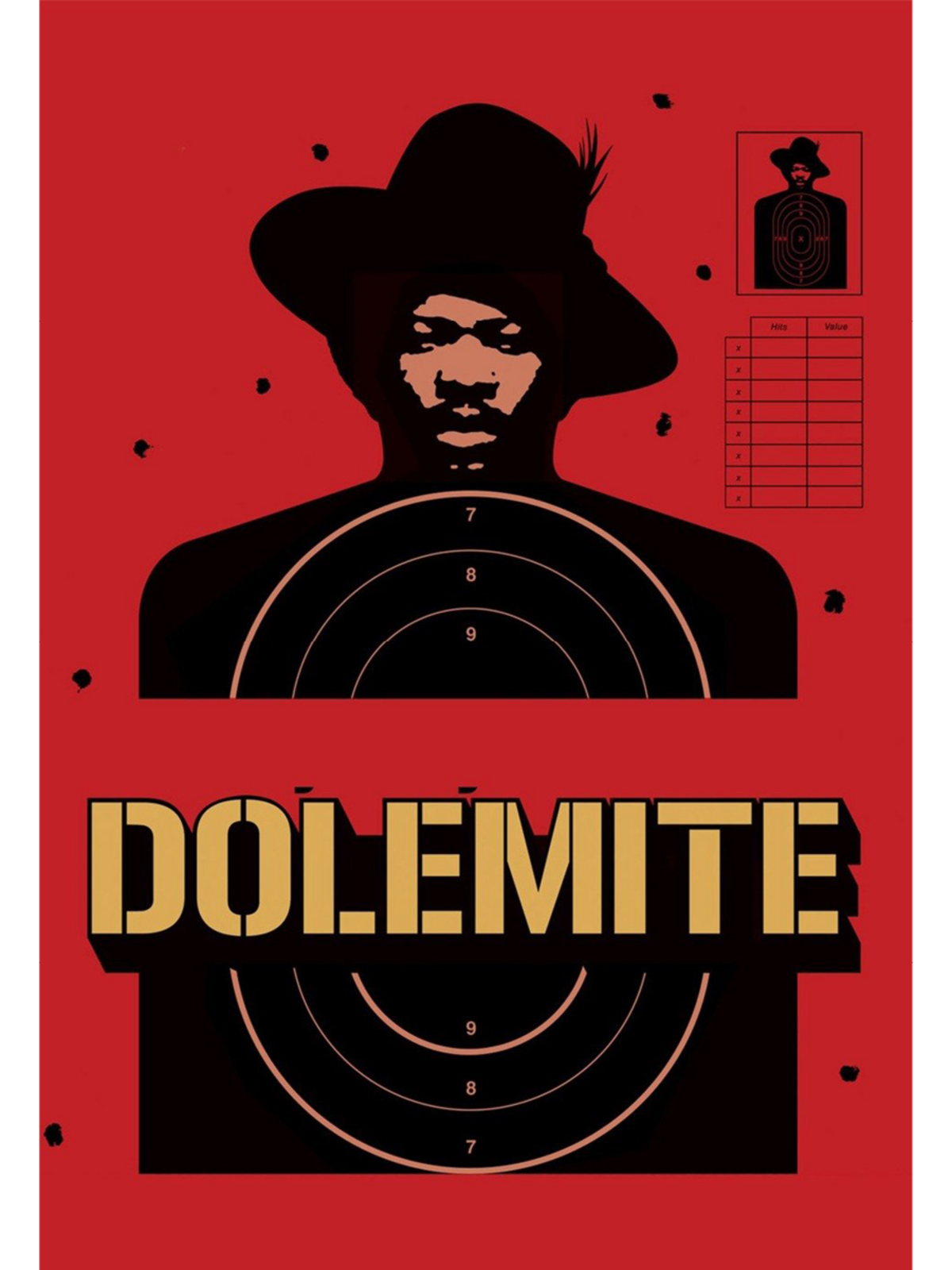

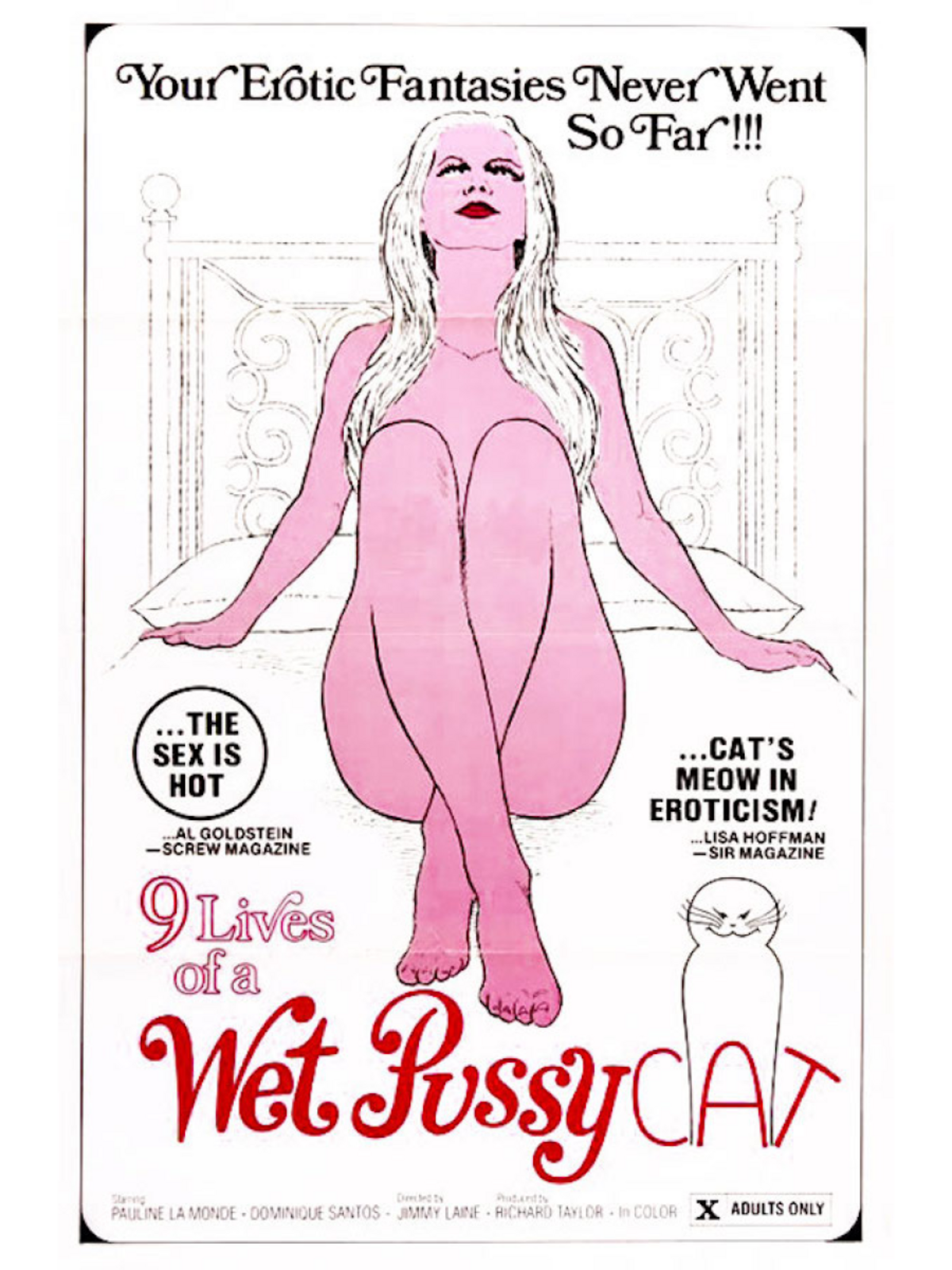

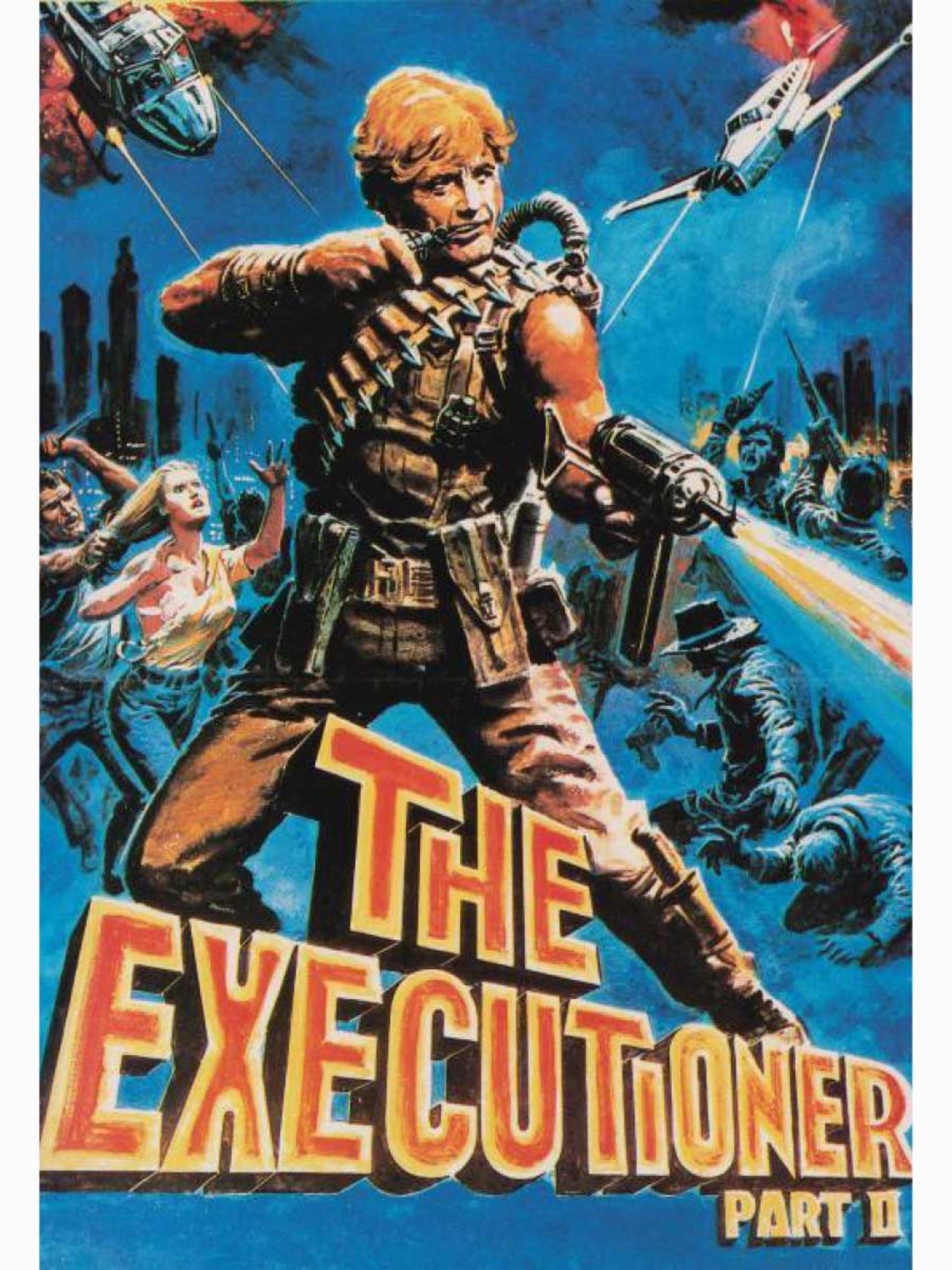

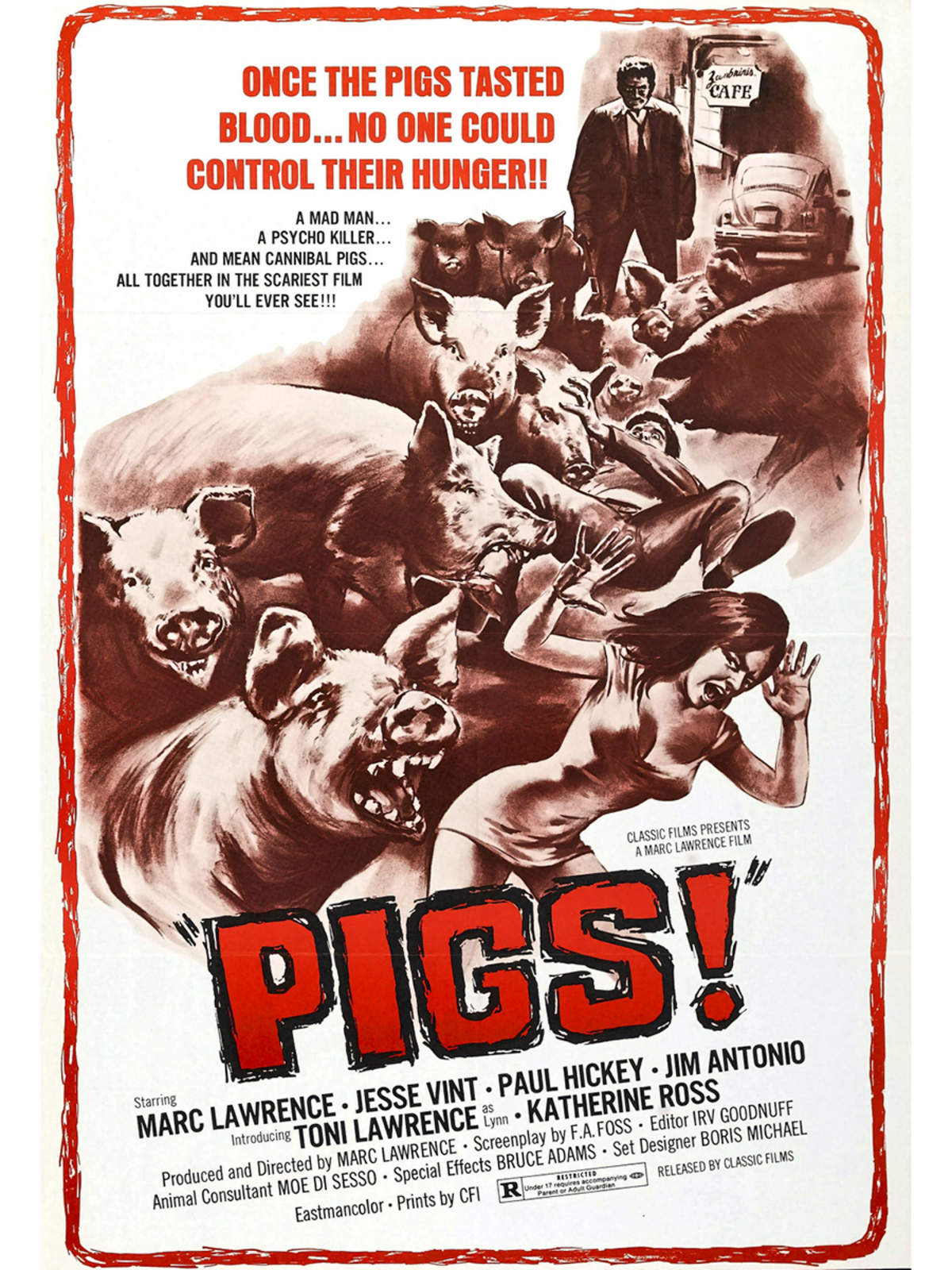

If culture is to be preserved with true fidelity, most qualitative notions of canon-worthiness need to be disregarded. It’s important that schlock and sleaze be embraced as warmly as sophistication. This is perhaps most applicable to the archiving of film, where exploitation and sexploitation flicks can yield just as much valuable—and, in some cases, more accurate—information about time and place as mainstream classics. For instance, does Martin Scorsese’s beloved Mean Streets portray New York City more vividly than, say, Andy Milligan’s seedy masterpiece Fleshpot on 42nd Street, which came out the same year?

Enter Vinegar Syndrome, a high-end film-restoration-and-distribution company whose focus is on the cinematic low end. The company takes its name from the chemical reaction that deteriorates older varieties of film stock. When they’re poorly stored for long periods, prints literally turn to vinegar. The team’s mission to preserve is “a race against time,” particularly when it comes to long-neglected genres and underground films. “I think what we do is … very important work because, in many cases, if we don’t preserve them, no one else will, and the film could become lost,” says Joe Rubin, Vinegar Syndrome co-founder. What the Criterion Collection is to art-house A movies, Vinegar Syndrome is to grind-house B (and, in some cases, C–Z) movies.