Twenty-five years and a few months ago, as I flew to Los Angeles to be with friends of Nicole Brown Simpson, whose risk-filled, fatal marriage to O. J. Simpson I had written a book about, I chose as my plane reading Susanna Moore’s new, murder-laced novel, In the Cut. Like virtually every reviewer, I was knocked out by the escalating erotic mayhem that the book’s protagonist, a female N.Y.U. English professor, is drawn into. The proximity of obsession and murder to “normal” life spoke deeply to me at the moment that Nicole’s friends were revisiting fraught, darkly complicated moments in the couple’s life.

In the Cut was the fourth of Moore’s seven novels, which were published from 1982 to 2010 to enormous critical acclaim. (“Utterly wonderful,” said The Washington Post’s Jonathan Yardley of one, while Michiko Kakutani has called her early novels “fiercely observed” and “evocative.”) These and her memoirs have earned Moore prestigious literary awards and lecture appointments at Princeton and Yale.

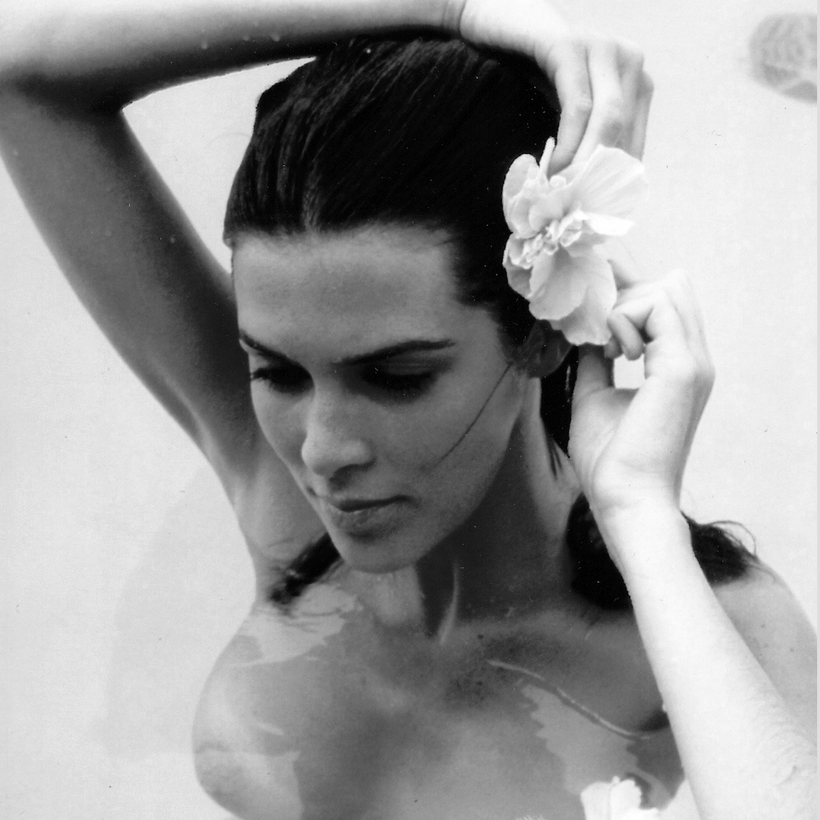

But, before these impressive accomplishments, Moore started out as a power-sensitive, innately sophisticated and discerning, but only fuzzily ambitious beauty on the rise in the midst of the momentous cultural sweep of the early 60s to the mid-70s. Here begins her newest memoir.

Growing Pains

I was quickly taken by the bemused but vulnerable, winsome ingénue who had, at 17 in 1963, been booted out of her home in upscale Honolulu by her widowed father and, mainly, by his new wife, after her own mother died, mysteriously, at 35. Susan (she would later rename herself Susanna) was taken in by her working-class maternal grandmother in a dreary Philadelphia neighborhood.

Moore writes movingly of the deep pain she experienced after the loss of her mother, tempered only by such momentary interruptions as the arrival of boxes of stunning designer clothes from Ale (Al-lie) Kaiser, Moore’s moneyed older female champion. In these clothes the young Moore knew “I could not help but look well in them.” Melancholy was never far away, though, and neither was Moore’s insecurity about quitting college early. I felt her lacking a sense of direction during those raggedy, end–of–Mad Men days when young women faced the choice of being either brains-hiding lovelies to be plucked by go-get-’em men or (those rare outliers) sexless professionals.

Moore grew up in the midst of the momentous cultural sweep of the early 60s to mid-70s.

After a couple of years in Philadelphia, Moore moved to Manhattan to work in a department store; it was a time when TV shows featured “girls in very short skirts, towering hair, and white vinyl boots danc[ing] on top of Lucite boxes.” Piquantly soulful, Moore found “refuge in the secret Bergdorf’s … wander[ing] from the gloomy employees’ cafeteria … to the large humming room where the silent tailors and seamstresses sat at rows of sewing machines.” She began her modeling career when, barely 20, she was chosen as “Miss Aluminum” by the Aluminum Association of America; this tacky honor (which involved parading around in a “tight, sleeveless sheath in a glittering silver material” in front of male executives) was representative of the era’s jaunty, clueless insults to women.

Moore tells of the time she was violently raped by the American fashion designer Oleg Cassini, who had asked her to model his collection; she thought he was, at 55 years of age to her 20, “the ideal of sophistication”—as women so often did back then. The chillingly described rape occurred during her brief, uncomfortable life as the perfect helpmeet wife to a Northwestern grad student who was the first boy she slept with. It’s easy to sympathize with Moore’s embodiment of the painful, deeply sexist strictures of those years.

South and West

The book takes a distinct turn when Susanna leaves New York for Los Angeles. It is 1967, a culture-snapping year. Her life quickens and toughens; when her luggage is stolen after a pretty-girl role in a Dean Martin movie takes her to Acapulco (in the midst of her affair with a lover as married as she still is), Moore buys a whole new wardrobe in place of the clothes lost. “My past was dropping from me piece by piece,” she wrote, “husband, clothes, even my toothbrush.”

But, while I shared the same kind of sensibility reading the first portion of the book as I had when I read In the Cut all those years ago, the second half has a ratio of (perhaps unintended) name-dropping to thoughtfulness that made it difficult to root for the young heroine as wholeheartedly as I had during those more poignantly described earlier years. Do we female readers slightly resent beauties who win more than they lose? Is this terrifying moment in time making us impatient with tales of glamour we might have otherwise enjoyed? Both things may be true.

Moore is promptly taken under the wing of “Old Hollywood” Beverly Hills hostess Connie Wald, quickly becoming like a daughter to her. Moore attends the doyenne’s dinner parties, where she is seated near Wald’s best friend, Audrey Hepburn (who admonishes Moore that she must “always wear shoes the same color as your hose”); James Stewart (within whose earshot, she is warned, she must not criticize the Vietnam War); and the couple with whom she’ll develop a long-lasting friendship: Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne. (At the time, Didion was so insistent on using only her married name in her personal life that when Moore once introduced her as Joan Didion, the Slouching Towards Bethlehem author replied, “You seem to have forgotten who I am.”)

Connie Wald’s world, Moore comes to see, is “exclusive and constricted, provincial despite its pretensions, and surprisingly vulgar.” She moves on a bit, eventually becoming a script reader for Warren Beatty, who hires her after—at his urging—she dutifully names all the people she knows in Hollywood and who “was obsessed with Joan Dunne” because, almost singularly among women, Joan “showed no interest in sleeping with him.”

In those raggedy, end–of–Mad Men days, young women faced the choice of being brains-hiding lovelies or (those rare outliers) sexless professionals.

In 1970, when she is 24, Moore meets the dashing film-production designer Dick Sylbert, and moves into the beach house Sylbert shares with “talkative, nervous, impatient” Roman Polanski—who is recovering from the murder of his wife, Sharon Tate—and their frequent houseguest Jerzy Kosinski. She has a liaison with Jack Nicholson, whom she met on the set of Mike Nichols’s Carnal Knowledge (for which Sylbert is production designer), and she reads scripts for him as she had for Beatty. Hungry for more, Moore devours Faulkner and Trollope and Auden and Bellow. John Dunne encourages her to write, but Moore is still unformed, insecure, and—these moments give the book heart—haunted by the tragedy and irresolution of her mother’s early death.

Moore marries Sylbert, and, as he works on Polanski’s Chinatown and Beatty’s Shampoo and becomes the vice president of production at Paramount under Robert Evans, she realizes that marriage has actually made her more insecure. It’s a heady world she’s in—the top-quality tier of early-70s Hollywood, and her intimacy with it both impresses and entertains. Still, sometimes her breathless list of eminences—Marcel Ophüls, Sven Nykvist, Isabelle Adjani, Hamilton Fish in one fell swoop—makes Moore seem blithe, even though the gravity of her writing proves she’s anything but.

Reflecting the durability of sexist self-expectation even among young women with great social privilege, Susanna Moore is still reading scripts for Nicholson, at $150 a week, when, at the end of the book, she bundles up the little girl she’s had with Sylbert and leaves the marriage to make her way on her own. “I would find a place to live. And a real job,” she resolves, in the closing sentences. “There was something I could do. I would be all right.”

Moore’s flowering into a lauded novelist would come soon after. She had within her all along a seriousness, substance, and self-motivation hidden beneath her enviable beauty and bolstered by her secret existence as one of “the mournful … [feeling] guilty while innocent.” In her review of Moore’s 2012 novel, The Life of Objects, Emily St. John Mandel praised the World War II–era protagonist’s “transformation from a passive and dependent girl to a bold and independent adult.” She might have been speaking of the leap Moore herself is about to take at the end of this memoir.

Sheila Weller is a journalist and the author of eight books, including, most recently, Carrie Fisher: A Life on the Edge