The story of rootless young Americans abroad in the 1920s long ago calcified into literary myth, but the entwined story of their engagement in journalism and international politics still offers plenty of surprises. In her fascinating new book, historian Nancy F. Cott follows four young college graduates who booked passage in the early 1920s to distant shores, carrying with them literary ambitions that were more or less vague, and wound up in the vanguard of interwar journalism.

Their ambition, restlessness, and curiosity met with a publishing world ready to exploit their talents. Many American newspapers had opened overseas bureaus during World War I, and kept them open into the 1920s, competing fiercely for readers. The peace was proving unstable and full of stories: of the conflicts that flared in the wake of the Treaty of Versailles’s radical re-drawing of the world map, of the progress of the Soviet “experiment” in Russia, and of the takeover of Italy by Mussolini’s Fascists. Even though American politics tended toward isolationism, readers were eager for daredevil first-person reports from “exotic” locales. The job of foreign correspondent was financially unstable and personally risky, but it carried an irresistible glamour.

Fab Four

Dorothy Thompson, James Vincent “Jimmy” Sheean, John Gunther, and Rayna Raphaelson varied in their backgrounds and experiences, but all were eager for self-discovery. In Vienna and London, Beijing and Moscow, Berlin and Paris, and many points in between, they encountered widely divergent political, cultural, and moral standards—and many opportunities for fleeting or lasting romantic connections. Sheean, a tall, redheaded Midwesterner who wore, he said, “the map of Ireland in my face,” found that his sexual attraction to men could be indulged with some degree of openness in Europe, and that he could benefit from the patronage of a network of prominent gay men, including the British diplomat Harold Nicolson.

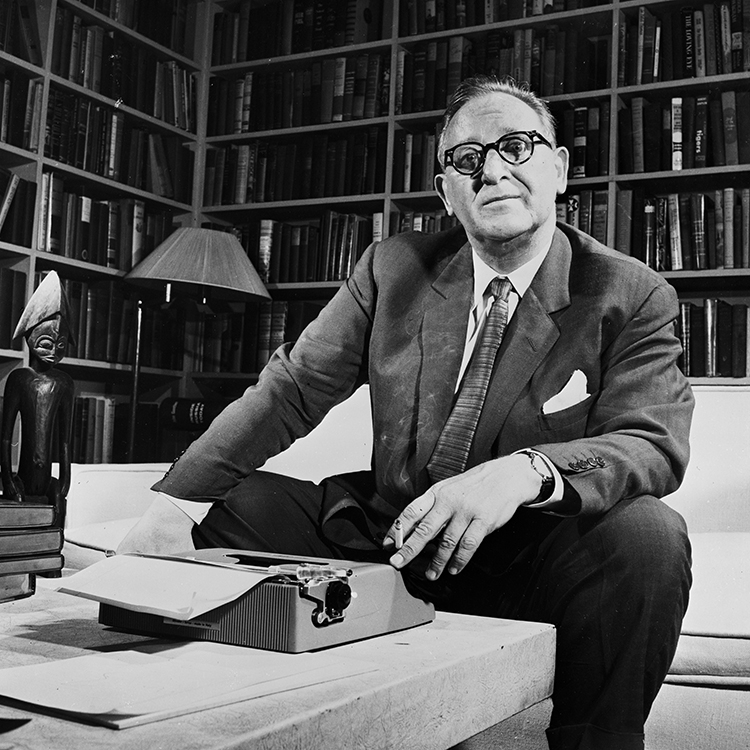

Sheean’s Chicago compatriot and friend Gunther was rapidly cured of his sexual innocence upon going abroad, and his romantic entanglements continued after his marriage. Fidelity and domestic harmony were hard to reconcile with the correspondent’s peripatetic, intensely social, and hard-drinking lifestyle. Certainly this was part of its allure, and, in the end, part of its cost.

While plenty of young American women in this era doubtless felt the same urge to travel abroad as men did, it was unusual for them to actually do so. Thompson, 27 years old when she sailed to Europe in 1920, was nothing if not unusual. From overcrowded Paris she struck out for Vienna, a struggling and wounded city after the war, and studied hard to become an authority on Central Europe. Her star only rose from there. By the mid-1930s, she was a household name in America—as a syndicated columnist, radio personality, the wife of famous novelist Sinclair Lewis, and one of the country’s loudest voices warning of the threat of Fascism worldwide.

The job of foreign correspondent was financially unstable and personally risky, but it carried an irresistible glamour.

Cott’s fourth subject, the flame-haired young Jewish woman Raphaelson, sailed for China in 1923. Her journey offers an important counterbalance to the Eurocentric journeys of most young Americans abroad, though it was spurred by the same spirit of adventure and began in a similar way, with the hunt for work and a home. Raphaelson spent time in Shanghai and Beijing, and by the middle of the decade found herself bearing witness to the Chinese Nationalist revolution. After meeting Sheean in China, they became close friends, before her tragic early death, in Moscow, where both had traveled for the 10th-anniversary celebrations of the Russian Revolution. Naturally, Thompson was on the spot as well.

Any one of these careers would make a fascinating subject, but it’s Cott’s account of the writers’ friendships, and their collaborative struggle to make sense of a world in flux, that makes the book stand out. All of them wrestled with the challenge of objectivity, a relatively new principle in journalism at the time, versus their own political beliefs. Sheean’s and Thompson’s careers, in particular, were inextricably tied to the fight against Fascism, and they found themselves somewhat unmoored after the war. Back in the 1920s, being Americans abroad had allowed them to represent democracy as an ideal and detachment as a policy. But as one of the two Cold War superpowers, the United States was actively directing the fate of foreign nations, and American journalists came under suspicion as tools of the state.

The heroic foreign correspondent was a myth belonging to a particular time and place. But today, as the threat of authoritarianism rises around the world and “America first” insularity once again competes with a more global outlook, the need for informed and authoritative reporting is more urgent than ever.

Joanna Scutts is the author of The Extra Woman: How Marjorie Hillis Led a Generation of Women to Live Alone and Like It