For even the most dexterous of Dickensian novelists, portraying an entirely invented community in a way that feels fully realized is a daunting challenge. Following bombastic entrances, tertiary characters tend to gray and recede; areas of the map remain maddeningly opaque; colorful asides, doled out liberally and with great gusto in the opening salvo, give way to the demands of narrative progression. The camera zooms in close and locks its gaze on our hero or heroine in order to streamline proceedings. In general, these are understandable and necessary sacrifices, as even the most gleefully shaggy picaresque requires some judicious shearing lest it begin to sweat and teeter. It’s a rare writer who can conjure a truly fulsome fictional microcosm without sacrificing momentum.

In the past, James McBride—the National Humanities Medal recipient and National Book Award–winning author of 2013’s The Good Lord Bird—has proven himself to be just such a writer. He has done so again with Deacon King Kong, his latest cacophonous, bighearted offering.

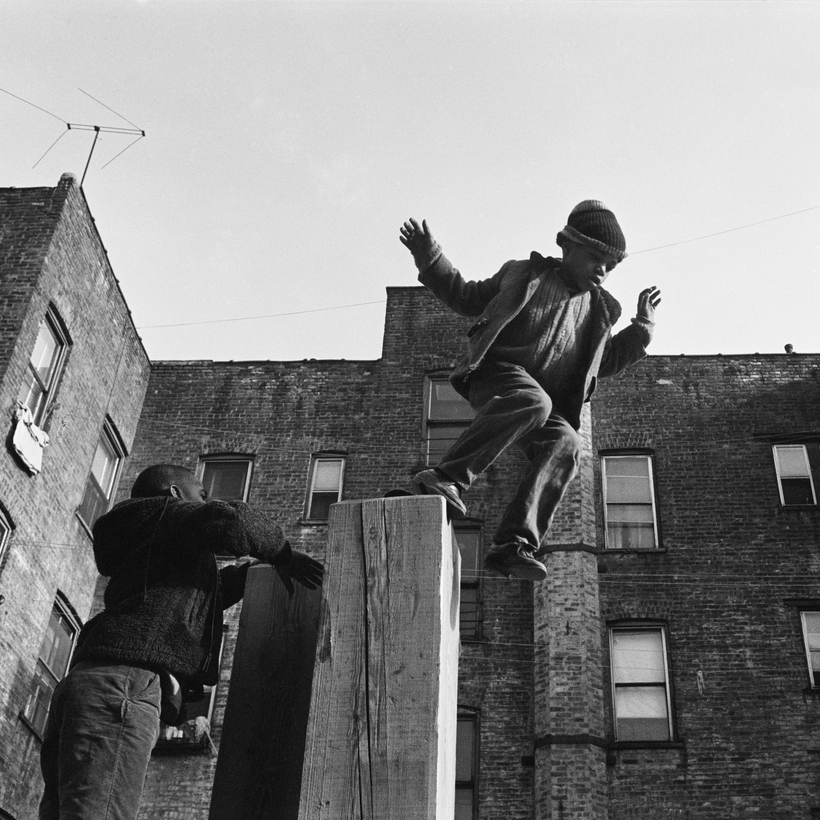

Another Brooklyn

Deacon King Kong is the tale of 71-year-old South Carolinian transplant Cuffy Jasper Lambkin, dubbed “Sportcoat” for the garish jackets he wears each day. He’s a perpetually drunk handyman, onetime neighborhood baseball umpire, and sometime deacon of the Five Ends Baptist Church, which sits in the shadow of South Brooklyn’s Cause Houses housing project.

The year is 1969, and tensions are rising between the community’s Old Guard—a quarrelsome but tight-knit group of well-meaning opportunists and beleaguered laypeople, scorned and abandoned by the city’s white powers that be—and an upstart wave of teenage drug dealers led by Deems Clemens, a former protégé of Sportcoat’s, who turned his back on a promising baseball career in favor of slinging dope for shady kingpin Bunch Moon, the novel’s only true villain.

The protagonist is a perpetually drunk handyman and sometime church deacon.

One September afternoon, having consumed an ample quantity of his janitor pal Rufus’s “King Kong” moonshine (“You could sell this stuff like hoe-cakes if it weren’t named after a gorilla”), and conversed at length with an apparition of his dearly departed wife, Hettie, Sportcoat, in front of 16 witnesses in the project’s courtyard, produces a .38 pistol and blows Deems’s ear clean off.

After that, all manner of hell breaks loose in the dilapidated Cause Houses. Old grudges are resurrected, assassins are dispatched. Rumors circulate at tornadic speed, and everyone, from the waterfront mobsters to the Irish-American beat cops, is thrown into a state of abject pandemonium. Sportcoat, meanwhile, having no memory of what he has done and even less time for those who attempt to explain it to him, saunters through his days like a well-lubricated and increasingly cantankerous Mr. Magoo, blithely dodging annihilation while imploring Hettie’s ghost to tell him where she hid the church’s Christmas Club money.

Taste of Honey

Although Deacon King Kong is ostensibly Sportcoat’s story, McBride’s novel is less concerned with the motives and fate of its titular character than with depicting the richness and variety and complex humanity of life in and around the Cause Houses. Within this multicultural beehive are a hundred internal dramas unfolding at once, and we are made privy to the intimacies and emotional nuances of damn near all of them: noble den mother Sister Gee’s tentative romance with the sympathetic Officer “Potts” Mullen; Deems’s convalescent ruminations about the nature of success and revenge in the projects; amiable giant Soup Lopez’s prison conversion to the Nation of Islam. The cast of characters is legion, and with the agility of a base runner McBride zooms from consciousness to consciousness, advancing the plot in small but powerfully charged increments.

It’s a rare writer who can conjure a truly fulsome fictional microcosm without sacrificing momentum.

As you can imagine, a book like this is not without its excesses. Do we need, for instance, a subplot about a melancholy gangster named the Elephant and his search for the Venus of Willendorf; or the third-act introduction of a femme fatale hit woman with vengeance on her mind; or a magical-realist chapter detailing the annual infestation of red ants, Colombian stowaways that made their way to America in an adulterous factory worker’s lunch box? Probably not—but I thoroughly enjoyed their inclusion nonetheless.

The novel is, if you’ll pardon the cliché, a consummate love letter to a disappeared world, and like all good love letters, Deacon King Kong has the occasional tendency to stray too far into the weeds of digressive rhapsody (tolerances for Potts’s and the Elephant’s heartsick musings may vary), but the buoyant musicality, the sheer effervescence of McBride’s dialogue, makes every street-corner sermon and protracted, pugnacious interaction (and there are many, many of these) a pleasure to be savored. In truth, I could listen to these people argue and reconcile with one another for a thousand more pages.

Dan Sheehan is the Book Marks editor at Lit Hub and the author of Restless Souls