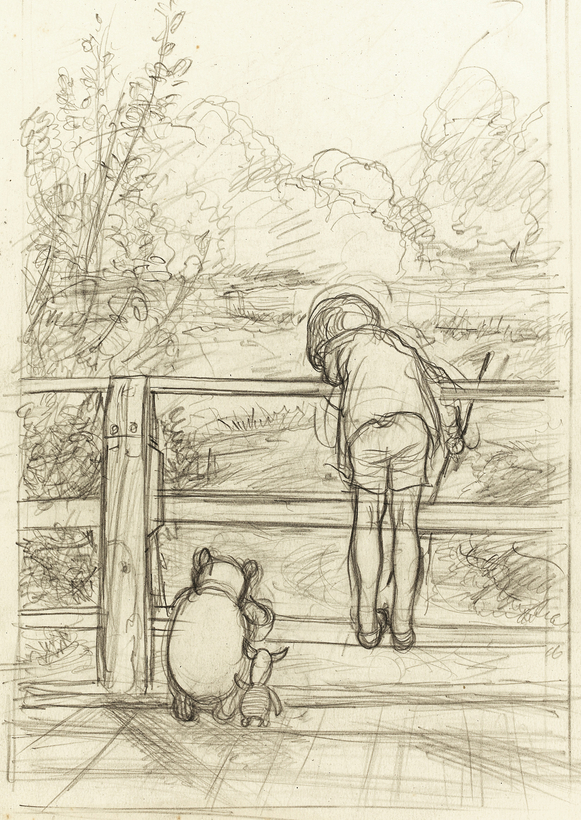

The principle that locates the universal in the particular couldn’t have a better avatar than Winnie-the-Pooh. The “silly old bear”—who originated in the playtime imagination of a young Christopher Robin Milne, and was subsequently burnished by his father, A. A. (Alan Alexander)—has long since slipped the bonds of English nursery literature to become a global brand, nearly as ubiquitous as the Nike swoosh (except in China, where depictions of Pooh have been censored in recent years after satirical comparisons between him and President Xi Jinping went viral).

Everywhere else, as The New Yorker’s St. Clair McKelway wrote, “the likeness of Winnie-the-Pooh is obtainable on spoons and knives and forks, on chinaware, on jars of honey (spelled ‘hunny,’ of course), on soap, on bibs, dresses, suits, coats.” The article goes on, or went on, since it was written in 1935, long before Disney got its Midas mitts on Pooh in the 1960s. Now there are a zillion more products, plus a half a zillion animated movies, spin-off books, video games, and the 2018 live-action film in which Pooh is reduced to teaching an uptight, workaholic, adult Christopher Robin (played by Ewan McGregor) how to be a better dad—as if Mary Poppins wasn’t available in the next corporate suite.