The phrase “Bright Young Things” was dreamed up by an unknown journalist almost a century ago. It conjured a social phenomenon: a collection of privileged youth, famed from the mid- to late 1920s for their tireless hedonism, who symbolized an almighty rupture with a world still fixated upon the Great War. Iconoclasts with Burke’s Peerage pedigrees, the Bright Young Things laid waste to the past with yah-boo-sucks heedlessness. They were frivolous, and thus should have been easy to dismiss, but frivolity was the point—for where had good behavior gotten the previous generation? It was a fair question.

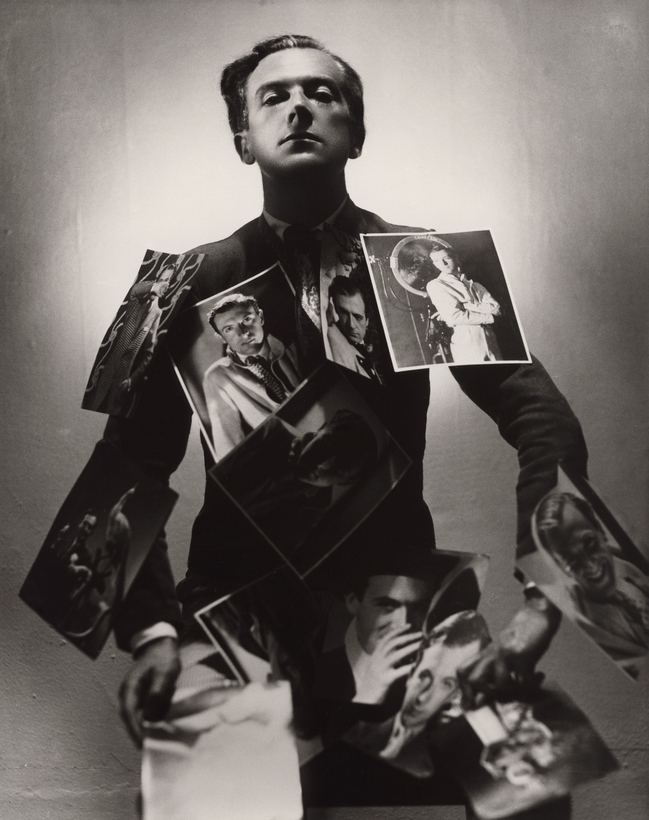

Recognizing that here was, indeed, a phenomenon, the newspapers tantalized their readers to tea-spilling distraction with the febrile antics of such characters as the Labour M.P.’s daughter Elizabeth Ponsonby and the baron’s son Stephen Tennant, who became early media celebrities; tales of treasure hunts through London, parties in swimming pools with “bathwater cocktails,” and costume balls and nightclubs; and the relentless jabber of the new slang (“How too too sick-making”). Now, as the 20s roll around once more, the National Portrait Gallery stages “Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things,” a celebratory exhibition of photographs and paintings.