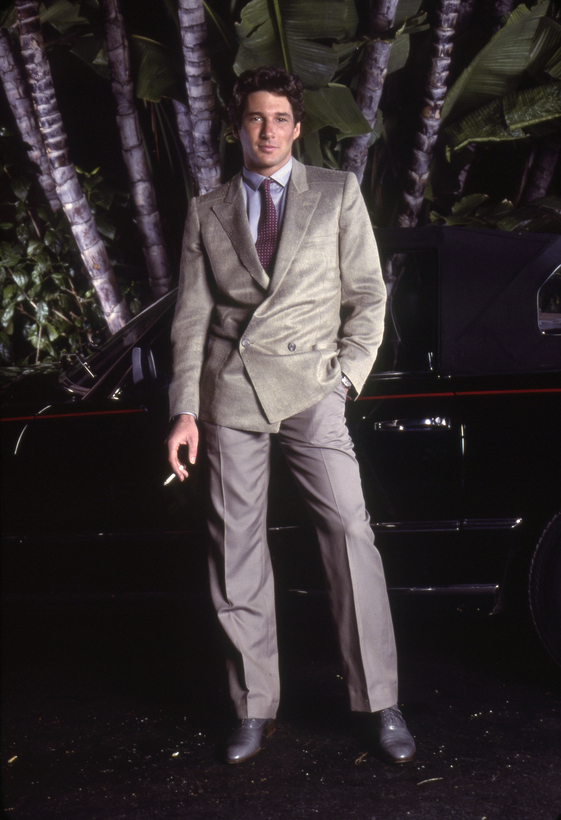

American Gigolo, about high-class stud and phallic martyr Julian Kaye, who bestows orgasms upon the love-starved matrons of Beverly Hills the way Jesus bestowed loaves and fishes upon the starve-starved multitudes of Bethsaida, turned 40 on February 1. Which means this erotic thriller, written and directed by Paul Schrader, maintaining perfectly that precarious balance between purity and profanity, art and trash, and starring Richard Gere, at his preening, narcissistic best, is now as old as its protagonist’s ideal trick.

Ugly things happen in American Gigolo, including murder, and the souls of its people are often warped, dark, demented, and strange. Their exteriors, however, are immaculate; sunlight and money give them a sheen, an iridescent glory and glow. Feeling bad has never looked so good. (Julian doesn’t kill, but thanks to a then unknown Giorgio Armani he’s dressed to.) And the movie, in thrall to youth though it is, has aged spectacularly, its mood as gorgeous as it was in 1980—gorgeous, yet hinting at sickness, both physical and spiritual, and full of noir dread.

Now, before we start this history (oral, naturally; Julian wouldn’t stoop to missionary position, so why should we?), I’ll whisper in your ear the words Julian whispered in the ear of a nervous first-time client: “We’re going to have a lot of fun. I can tell … Just lie back and relax … I know what you want … Close your eyes, baby … Leave everything to me. I’ll get you wet. I can take care of you.”

Part One: Finding the Man

JAMES TOBACK, writer-director: It was the early 70s. Jim Brown [running back, actor] was having a party at his house. That’s where I met Val. He was by the pool—around 30, reasonably good-looking. We started chatting, and two things became clear to me. The first was that Val was a gigolo. And the other was that among his customers was Barney Rosset [owner of Grove Press]. Val described to me a scene with Barney and his wife that was similar to the Palm Springs scene in American Gigolo [a husband pays to watch Julian have rough sex with his wife], except different in the sense that the scene in the movie was nasty and unpleasant. What I heard from Val was that he was pleasing the wife and Barney was watching from the closet and emitting a high-pitched “Whoo, whoo.” So it was all good-natured, nothing angry or mean about it. I was spending a fair amount of time with Paul Schrader then. I told him about Val, and it must’ve planted a seed in his mind.

PAUL SCHRADER, writer-director: Jimmy said that? First time I ever heard the story. No, Julian Kaye doesn’t have a realistic counterpart. He isn’t any more a gigolo than Travis Bickle is a taxi driver. [Schrader wrote Taxi Driver.] I’ve taken to describing this type of film as a man in a room, alone, wearing a mask, waiting for something to happen, and the mask is his occupation. Speaking of Jimmy, have you seen Uncut Gems? Terrific film. I was watching Adam Sandler and I thought, This guy went to school on Jimmy Toback. The Jewishness, the white negro-ness, the sexual obsessions, the gambling obsessions—it’s him. Sandler created the Toback character that Toback has been trying to create for 30 years!

The New York Times, “Travolta to Play a Gigolo,” May 3, 1978: The newest Hollywood star, John Travolta, has agreed to make yet another movie—Paul Schrader’s “American Gigolo.”

SCHRADER: John Travolta was the logical choice at that time. Everybody wanted John. And Julian Kaye seemed a natural segue from Tony Manero [Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever]. He did that photo shoot with Paul Jasmin that was in Variety—John unshaven in a white suit, which was reflective of both Gigolo and Saturday Night Fever. Then I got a call from Kit Carson [actor, screenwriter], who’d been living with Karen Black [actress, Scientologist]. He said, “You didn’t hear this from me, but John’s been talking about dropping out in the Scientology meetings.”

I knew that if John was talking about dropping out, he was going to drop out. There were three reasons. One, his mother had just died and he was in a deep funk. Two, he’d had his first embarrassing flop [Moment by Moment with Lily Tomlin]. And three, he was freaked by the homosexual stuff. He was very much in the closet at that time, and started to realize that a lot of the people involved in the film were gay, and that it’d be a gay take on the material, even though his manager, Bob LeMond, was very gay. Maybe it was Bob himself who started getting uncomfortable. Anyway, in that era, bad news always happened at five o’clock on Friday because you created the bad news, got in your car, and nobody could reach you till Monday. Sure enough, on Friday John was out. I had two days to try to figure out who else before shit hit the fan.

PAUL JASMIN, photographer, poster designer: I knew Richard early, when he was in the chorus of a Broadway musical [Soon, 1971] with Peter Allen, a good friend of mine. I was the best man when Peter married Liza Minnelli. People were already talking about Richard then. Richard was very smart, very keen. He just knew how to work it.

MICHAEL SEGELL, from “Richard Gere: Heart-Breaker,” Rolling Stone, March 6, 1980: Back in the old days—two years ago—the industry cautiously labeled Gere “semi-bankable” after his impressive performances in a string of movies [Days of Heaven, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, Bloodbrothers, Yanks] that flopped like bloated fish.

SCHRADER: During this period, three well-known actors dropped out of three films, and the replacements all became stars. George Segal dropped out of 10; Dudley Moore became a star. Richard Dreyfuss dropped out of All That Jazz; Roy Scheider became a star. John Travolta dropped out of American Gigolo; Richard Gere became a star. I wanted Richard for the part. Richard didn’t have enough heat, though. Barry Diller [the head of Paramount] went to Chris Reeve, but I thought Chris was too all-American, didn’t have that reptile mysteriousness. So I called Chris’s agent and said, “I don’t think Chris is right for this.” That well was poisoned. On Sunday I went to Richard’s house in Malibu. He was watching the Super Bowl. I told him I needed an answer. He said, “You can’t say I have three hours to make this decision. That’s not how I work.” I said, “That’s the situation I’m in. And when this game is over I’m going to leave, and if you haven’t said yes, it’s no.” The game ended. He said, “O.K., I’ll do it.”

Then I scurried over to Barry’s. Now, at that time, you did not speak to studio executives on weekends. I rang the bell, put a note on the gate, went home. An hour later Barry called. He said, “How dare you? I have guests over.” I said, “I just offered the part to Richard Gere and he’s accepted.” Barry said, “You weren’t authorized to do that.” I said, “Look, Freddie Fields [producer] is steaming mad. He thinks he can keep John off the marketplace for six months by enjoining him, and Freddie very much wants me to be part of this lawsuit. On the other hand, I want to make the film. So, Monday, when the trades contact you about John dropping out, it can be ‘Travolta has dropped out, Freddie Fields is now suing Paramount. The project has collapsed.’ Or it can be ‘We understand why John can’t do this at this time, and we’re moving forward with Richard Gere.’ And I know that you want John for Urban Cowboy. Urban Cowboy falls right square in that injunction range that Freddie is marking out for John.” So Barry said, “Let me get back to you.” An hour later, he called. It was Gere for Gigolo, Travolta for Urban Cowboy.

BARRY DILLER: I doubt I said, “How dare you?,” since I’ve had a life rule against the phrase. But, yes, the substance of Paul’s story is correct.

RICHARD GERE, from “Richard Gere: Heart-Breaker,” Rolling Stone: After Goodbar I had enough offers to play Italian crazies for the next 15 years. The bastards want to put you in a box with a label on it and crush it. If you have any hope of growing, of being taken seriously, you have to control the vultures.

SCHRADER: I wouldn’t have directed John any warmer than I directed Richard. Warming this character up would be like giving Travis Bickle a dog.

Part Two: Creating the Fantasy

SCHRADER: Los Angeles is probably the most photographed city in the world. The challenge was how to make it seem fresh. In the end, I turned to Italy—Giorgio Moroder for the music, Giorgio Armani for the clothes, Ferdinando Scarfiotti for the design. Nando was a young lover of Visconti’s and he’d worked with Bertolucci on The Conformist, and he comported himself like royalty. I approached him at a moment of real vulnerability because he’d just had a falling-out with Bertolucci. I said to him, “Come to America.” Six months before, or six months later, I don’t think he would have. He’s someone whose visual style transformed me, this idea that you can have a poetry of images rather than a poetry of words. You meet someone like that who also has personal charisma, and you’re really on the leash. I put him in charge of the look of Gigolo. That meant the design, wardrobe, props, cinematography—they all had to report to him.

JOHN BAILEY, cinematographer: Nando was very collaborative. His sensibility was Roman, refined, high-end, artistic.

DAVID FREEMAN, screenwriter: I lived where Richard Gere’s character lives—the Sunset Plaza Apartments, though they’re called something else in the movie [Westwood Hotel Apartments]. I don’t think there was a person there who wasn’t in show business. Teri Garr was like the mayor. Everybody had a crush on Teri, including me, but she was too smart to fuck the screenwriter. Robert Forster was there, and George Hamilton. I watched Paul shoot a scene by the pool, which had a light-blue tile and wasn’t shaped like a rectangle; it had curves, and there were always pretty girls in bathing suits around it. Anyone would look at that complex and know immediately that they were in L.A.

BRET EASTON ELLIS, from his book White: The gliding camera movements, the gorgeous sets, the dramatic lighting—all aiding in the creation of [Schrader’s] acid vision of Los Angeles as a brightly colored wasteland. This is a sunlit neo-noir, ominous and beautiful.

SCHRADER: I showed Purple Noon [René Clément, 1960] to Richard. I said, “Look at this guy, Alain Delon. He knows that the moment he enters a room, the room has become a better place.” And that’s what our character knows. Even though he may be looked at as trash, he knows he brings the glow, in the same way that a beautiful woman brings the glow.

BAILEY: I was intent on keeping background elements from intruding on the frame, because nothing should distract the eye from Richard. That’s why we often left walls undecorated. And, at the time, European soft-light key was dominant, but I often reverted, at least in the close-ups, to a classic undiffused hard light that was used in the studio era of the 30s and 40s.

DAVID THOMSON, from his book Sleeping With Strangers: [Gere] out-glamorized the dutiful female lead in the film…. There are constant suggestions in his look, his clothes, and his glamour that he is a surrogate female.

SCHRADER: Oh, yeah, having Leon [Julian’s pimp, played by Bill Duke] call him “Julie” was absolutely deliberate.

BILL DUKE, actor: Why does Leon call Julian “Julie”? For a lot of reasons. To make Julian feel like they’re buddies. To castrate Julian. But most of all to control Julian. It’s his way of saying, “Don’t forget, Julie, I’m the boss. You work for me.”

SCHRADER: I auditioned four or five girls for the role of Michelle [wife of a senator; Julian’s love interest]. Mia Farrow was really the best. But I tested her with John [Travolta], and she blew John off the screen. She made him look like an amateur, like a kid, not like the seducer. I had to go another way. Sue Mengers [agent] seized on this and invited me for dinner. She seated me next to Lauren Hutton. I tested Lauren with John, and he was much better with her. Then John drops out. I want Mia back. But I’m saying to myself, “Look, I’m playing a dangerous game with Paramount. I’m changing one piece in the puzzle—the lead actor. If I say I’m changing both pieces, will that give the studio the excuse to kill the project?” I got afraid and didn’t take the risk. Obviously I did everything I could and Lauren did everything she could to be as good as she could, but Mia just had stronger chops.

ELLIS, from White: Lauren Hutton plays Michelle.… and she’s quite stunning as well, but the movie loves its leading man.... Mainstream audiences had never seen a man photographed—objectified—the way Richard Gere was. The camera ogled his beauty, roamed over his skin, devoured his adolescent petulance, was hypnotized by his flesh, and Gere was the first leading man in a big studio movie to go full frontal.

GERE, from “Richard Gere on Gere,” Entertainment Weekly, August 31, 2012: [The nudity] wasn’t in the script. It was just in the natural process of making the movie. I certainly felt vulnerable, but I think it’s different for men than women.

Part Three: From “Man Machine” to “Call Me”

THE NEW YORK TIMES, “Giorgio Moroder Still Feels Love at 77,” September 15, 2017: “Mr. Moroder [is] the mac daddy of disco.”

SCHRADER: I wasn’t thinking of Moroder as disco. I saw him as part of the Kraftwerk/Jean-Michel Jarre/Tangerine Dream movement—European electronic music. I liked its alienated quality. I liked how propulsive it was, how sexual yet antiseptic. A sound for a new Los Angeles.

DEBBIE HARRY, singer-songwriter: Giorgio sent Blondie a demo of American Gigolo’s theme song. He’d written the music, and he’d also written the lyrics. “Man Machine” it was called then, and he wanted us to perform it. The band may have been in demand in those days, but we weren’t getting this kind of offer. These were all people we admired—we loved Giorgio’s work, and everybody knew up front that Paul was a genius. This wasn’t some exploitation thing—a punk song with three chords. This was a real collaboration.

GIORGIO MORODER, composer, D.J.: I first wanted Stevie Nicks, but that didn’t work out. Maybe Stevie didn’t like the movie, I don’t know. I wanted a woman to sing the song because I love women so much. I thought it would be sexy if a girl would sing these lyrics, which are the feelings of the guy—this gigolo—and very aggressive.

HARRY: Giorgio was a ladies’ man, and “Man Machine” came from the perspective of a guy with real machismo. I felt I couldn’t sing these lyrics, so I asked if I could write my own. Paul invited us to his suite at the Pierre, and we watched a rough cut. It was a woman’s picture, when you got right down to it. A man might brag about his sexual prowess, but I don’t think a lot of men would want to be Richard Gere’s character. He’s the subject, but he’s also the object, and that’s something I definitely related to. Chris [Stein] and I lived on 58th and Seventh in those days, which was only a few blocks from the Pierre. We walked back to our apartment, and that opening image of Richard Gere in his black Mercedes, driving the Pacific Coast Highway, was in my mind along with Giorgio’s music, and the first lines just came to me. “Color me your color, baby. / Color me your car.” Then the rest of the song just sort of wrote itself. The title had to be “Call Me” because those are the words Richard Gere says to all the women.

MORODER: Debbie did a fantastic job. “Call Me” quickly went to No. 1.

SCHRADER: The character of Julian is much more a movie star than he is an actual gigolo.

MICHAEL GROSS, “Even Richard Gere Gets Dumped,” Esquire, July 1, 1995: In 1978, [Gere] collected his last unemployment check.... “Does it bother you that you’re viewed as a sex object?” [Jane Lane of Ladies’ Home Journal] asked.... “You want to see a sex object?” Gere shot back, reaching for his zipper.

JASMIN: My friend Susan Pile [V.P. of publicity at Paramount] sent me to shoot Richard and Debra Winger for An Officer and a Gentleman. Winger signed on to do the movie. And they rehearsed in L.A., and there was a great chemistry between them. And she couldn’t wait to work with him. Then he brought his lover, a Brazilian girl, Sylvia [Martins], along, and so Winger didn’t like him at all. She just hated him.

GERE, from “Richard Gere: Heart-Breaker,” Rolling Stone: I never consciously thought about becoming a sex symbol when I accepted the part [of Julian Kaye]. But I suppose if you want to be up there—as a movie star, rock star, whatever—part of that is, yes, you want to be desired. And I suppose that is basically sexual. I wouldn’t say I did the movie specifically for that reason, but it’s part of wanting to be up there, of wanting to be watched and appreciated.

Part Four: Armani and Gravity Boots

SCHRADER: I made it clear beforehand that if Richard’s shirt is wrinkled, we stop shooting.

LAUREN HUTTON, from “Lip Service,” Harper’s Bazaar, February 27, 2014: Richard and I were jeans, T-shirt, and sneakers people, and to be done up in that heavy a drag was a rare thing for both of us.… We were absolutely acting.

GERE (possibly apocryphal): “Who’s acting in this scene, me or the jacket?”

SCHRADER: Richard, as an actor, was more interested in the character than the clothes, but to me the clothes and the character were one and the same. Remember, this is a guy who has to do a line of coke just so he can get dressed.

BAILEY: That scene where Richard is dressing himself, laying out potential options—shirts, ties, jackets—we shot over several days. It was a montage sequence, and cut to music [“The Love I Saw in You Was Just a Mirage,” by Smokey Robinson and the Miracles]. I don’t want to call it a music video, but it was balletic in a way, and choreographed. It turned out to be very influential visually. When I see it, though, I cringe because the lighting is mismatched.

HALEY MLOTEK, “Armani in America,” Lapham’s Quarterly, July 3, 2018: In 1975, its first year of business, Giorgio Armani S.p.A. did $14,000 in sales; the following year it brought in $90,000. By 1981, the year after Gigolo was released in theaters, company sales were $135 million.... This is an unprecedented commercial expansion. A rumor persisting to this day is that, because of Gigolo’s impact on Armani’s sales, Gere never has to pay for a single item of Armani clothing. He can walk into any Armani store, anywhere, and walk out with whatever he wants.

JASMIN: It was a very coked-up period of L.A. Everybody was just very high.

FREEMAN: I’m the least likely person to snort dope, but even I did it in those days. It was the magic powder.

SCHRADER: Anyone who says the first three or so years on cocaine isn’t fun is lying. But it does take its toll. The monster that you were enjoying starts enjoying you, and then you’re in the grips.

GERE, from “Richard Gere on Gere,” Entertainment Weekly: Paul came to see me in Malibu and said, “You’ve got to say yes to this tomorrow at the latest.” I read it and I thought, “This is a character I don’t know very well. I don’t own a suit. He speaks languages; I don’t speak any languages. There’s kind of a gay thing that’s flirting through it, and I didn’t know the gay community at all.”

SCHRADER: Julian was not as gay as he would be today. At the time, we thought we were being brave, promoting this androgynous male entitlement. Now I look back, and we were being cowardly. It should’ve been much more gay. Then again, I probably got it made because Julian pretends not to be gay. Barry probably wouldn’t have made it otherwise.

DILLER: I can only say that if Paul made Julian gay, we probably would have been even more enthusiastic about the movie.

FREEMAN: Paul was crazy in those days. I’m sure he didn’t leave anything untried. In fact, if he found something he hadn’t done, he’d stop everything so he could do it.

THOMSON, from Sleeping with Strangers: I would say that American Gigolo [is] the work of a talented man exploring serious uncertainty about the stability of his sexual orientation.

JASMIN: Paul [Schrader] was very fucked up. He’s very talented, but crazy. A lot of very talented people are very crazy. I remember being in a hot tub with him and there was a loaded revolver on the edge. He got really coked up and was playing Russian roulette. The whole scene—the hot tub, the revolver—was very closet-y. Nothing happened between us. If it ever had, he’d have had to shoot me. I realized, you don’t fuck … yeah.

SCHRADER: I was never really threatened by the homosexual thing, because I always knew that it wasn’t going to happen. The closest it ever came to happening was with Paul Jasmin, and it almost happened, but it still didn’t happen. But what did happen, at one point, was that there was a hot tub involved and a pistol. I don’t actually believe I played Russian roulette—I think I cheated and looked at the cylinder—but for my audience I really played. My friend Alan Stern called my psychiatrist. At one in the morning he comes to my house, and we have this long conversation. My gun, a blue steel six-cylinder revolver, is on the table. He’s just about to call Cedars to have me committed. I’m trying to talk my way out of this. Finally, he sort of agrees with me that I’m not a threat to my own life at the moment. But he says, “I have to take the gun.” Well, time goes by—I get married, have children. It’s 30 years later and I’m in Los Angeles. I’m curious, so I go to his office. He’s now in his mid-80s. I say to him, “I don’t know if you remember, but you came to my house in the middle of the night. I had a gun and you took it from me.” He opens a drawer and puts the gun on the table. He says, “I’ve kept this gun ever since, because it reminds me of what I really do for a living.” I say, “I don’t suppose you would give it back?” He says, “Oh no, I wouldn’t.”

THOMSON, from Sleeping with Strangers: It’s close to the point and far from an attack to say that Paul Schrader’s film aspires to the mood of a knockout poster.

JEAN PAGLIUSO, photographer: I took Richard to this building in the Bronx. It had nothing to do with the movie, but it had the look of the movie, of modern L.A. I knew how important Venetian blinds were in the movie. Venetian blinds have this noir feeling—you can both see the character and not see the character. And they give this sense of intimacy, like you’re spying on someone, and that’s how I wanted it to be. So I went to Pintchik, this little paint store, and bought a set and I hung them on a light stand.

SCHRADER: It was a black-and-white photo. Paul Jasmin drew everything in, and colored it. He even moved the position of the tie and changed the tie. You see the shadow of the tie? Paul put that in. All the subtle, little sexual qualities.

JASMIN: I gave it flair. That’s all I did. I gave the image flair.

HUTTON, from “Lip Service,” Harper’s Bazaar: The film was a critical success, but it didn’t make a penny when it came out.… I think it wasn’t a hit because you never get to see why he’s such a good gigolo. You never see how he makes love to a woman. I don’t think there’s a kiss in the whole movie!

SCHRADER: I heard someone from Paramount say that American Gigolo’s artiness kept it from Saturday Night Fever–caliber success. Quite possible. It’s also possible that its artiness made it the success, however modest, it was. I still get checks. It could have made more, of course, but it has been in profit for 40 years.

HUTTON, from “Lip Service,” Harper’s Bazaar: Little by little, though, the movie became a hit just because it was so brilliant. It was a stylish hit.

ELLIS, from White: Looking back, the impact American Gigolo had on me is impossible to tally.... It was new, it was gay, it ended up influencing everything from the popularity of GQ magazine to how Calvin Klein began advertising men…. In 1980 I was beginning the Less Than Zero project which would culminate in 1985 with my first novel’s publication, and though I took many of my cues from Joan Didion and LA noir … American Gigolo was another key template so much so that I named the male teenage prostitute Julian.

GERE, Italian Vogue, October 16, 2018: Paul kind of hit it.

Lili Anolik is the author of Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A.