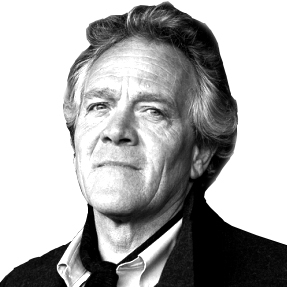

When right-wing commentators emerged from reviewing the former Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow’s Unspeakable demanding smelling salts and decontamination, I knew this might be a book for me. Disgust on one side of the debate these days seems to guarantee satisfaction, even pleasure, on the other. And besides, there are very few people whom I had watched more closely since Britain voted to leave the E.U. than John Bercow, the most prolix, irascible, and memorable Speaker in decades.

The reasons for Conservative loathing for the diminutive son of a Reform Jewish father and Methodist mother brought up on the wrong side of the tracks in North London are his journey from the far-right racist politics of his youth to a liberal position on the left of the Tory party—the exact opposite direction of travel to most of his colleagues—and, second, his staunch defense of Parliament against the executive through the tortured years after the Brexit vote.