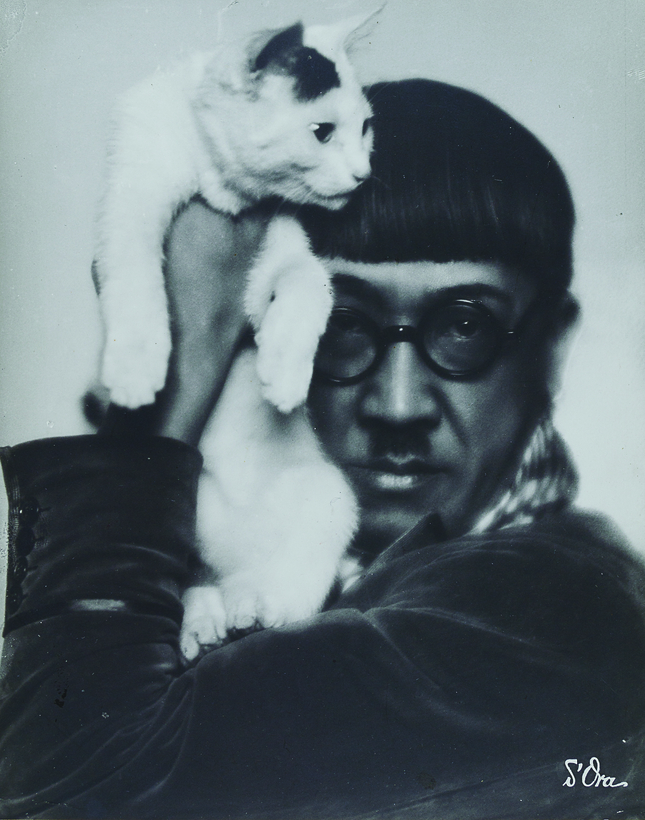

The glamour of the fin-de-siècle and the interwar years has the force of a doomed fairy tale, a mysterious energy that can be read, in retrospect, as deep denial of looming upheaval ahead. This glowing tension will be on view starting February 20 at the Neue Galerie, where a major retrospective on the Austrian photographer Madame d’Ora examines a career of 50 years, 1907 to 1957, through more than 100 photographs.

Dora Kallmus was born in Vienna in 1881 to a prominent Jewish family. Coming of age in an era when upper-class women dabbled in the arts as transitional pastimes until marriage, Kallmus instead saw photography as a career that could afford her financial and intellectual independence. She took courses at Vienna’s graphics institute, worked as an assistant to the German photographer Nicola Perscheid, in Berlin, and in 1906 re-christened herself “Madame d’Ora.” Her early subjects suggest she was both well connected—the Vienna bourgeoisie at the time was not sprawling—and hardworking: the list includes distinguished cultural movers such as Gustav Klimt, Karl Kraus, Alma Mahler, and Alban Berg.