If the Devil finds work for idle hands, busy little fingers must point toward heaven. And whatever way you take it, high fashion is embracing handcraft with renewed fervor.

On Thursday, Chanel took its exquisite craftsmanship to France’s Loire Valley and brought a whole new meaning to the “Château des Dames,” the affectionate name given to the Château de Chenonceau. Its residents have included powerful women such as Diane de Poitiers, Louise Dupin, and Catherine de’ Medici, whose interlacing double-C monogram conveniently echoes Chanel’s logo.

This extraordinary event of the coronavirus era was attended in person by only a single guest—the actress and Chanel face Kristen Stewart—and photographed by Juergen Teller, who captured the formal buildings and wild gardens in a modern spirit. Teller’s images have an overarching purpose: to promote and glorify Chanel’s belief in the power of human hands. And despite its scaled-down audience, the spectacle managed to have major impact as a marketing event, thanks to the virtual attendance of influencers and editors.

Chanel’s creative director, Virginie Viard, incorporated ideas of womanhood spanning centuries, including tailored jackets and a motif of checkerboard squares to complement the floor of the château’s grand ballroom.

“I love mixtures. I like mixing eras—the Renaissance and the 19th century, rock and a very girly side,” said Viard. “It is all very Chanel.” After having worked with the late Karl Lagerfeld for three decades, she has accepted his belief that traditional skills have to stay fresh to stay alive.

One way Chanel is dedicated to keeping the skills alive is to bring all the craftspeople in Métiers d’Art, as the house has named its handcraft ateliers, into a splashy new home, an ultra-modern building in the 19th Arrondissement known as Le 19M, which stands for Mains, Mode, and Métier. By this time next year, at least 11 different groups of artisans, from Lesage embroiderers to experts on pleating, knitting, hats, and shoes, will all be working in independent groups under a single roof.

Traditional skills have to stay fresh to stay alive.

“We were totally saturated in the center of Paris, so we needed to find a solution,” explained Bruno Pavlovsky, president of fashion at Chanel, where he has worked for 30 years. “We decided that we needed a strong building with something symbolic about it for this atelier to continue to exist and to be visible. Whatever you can do digitally and mechanically, you are not able to design and create a jacket or a silhouette. It’s a combination of all these people working together around an object and what they want to achieve.”

It is hard to feel the emotional connection to Chanel’s handiwork through a swift viewing online—another imposition of the coronavirus. So Viard sent out a collection with exceptional examples of every kind of decoration. Mixing elements from her own childhood, from today, and from the distant past, the designer made the show characteristically Chanel.

Meanwhile, the company has engaged with climate initiatives and issued sustainability-linked “Green Bonds,” which pledge its dedication to caring for our planet.

There is no doubt that, in the world of fine fashion, craft is having a powerful revival. In 2018, the Michelangelo Foundation launched a popular exhibition in Venice called “Homo Faber,” a sweeping study of art and craft in the Digital Age. It has been heavily supported by Johann Rupert, chairman of luxury group Richemont. This fall, as a response to the pandemic, it launched an online, searchable platform called Homo Faber Guide, which connects collectors and enthusiasts to artisans, museums, and experiences all over Europe.

“The idea is to give a voice to these talented masters,” explains Alberto Cavalli, executive director of the Michelangelo Foundation, who oversees the Guide’s recruiting efforts. “Often, they are not so familiar with the digital media, so the Homo Faber Guide gives them the opportunity to represent themselves and touch a wider public, and not only those associated with craftsmanship like France and Italy. What about Estonia, Norway, Portugal, and Sweden?”

One of Cavalli’s goals is inspiring a sense of awe and wonder. But, he warns, “These occupations must be viable, so that [artisans] are happy, and expressing their talent every day to create marvelous things.”

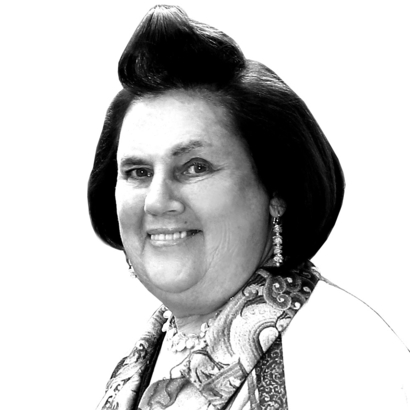

Suzy Menkes is a storied fashion journalist and the author of several books, including The Royal Jewels and Fashion Designers A-Z: Etro Edition