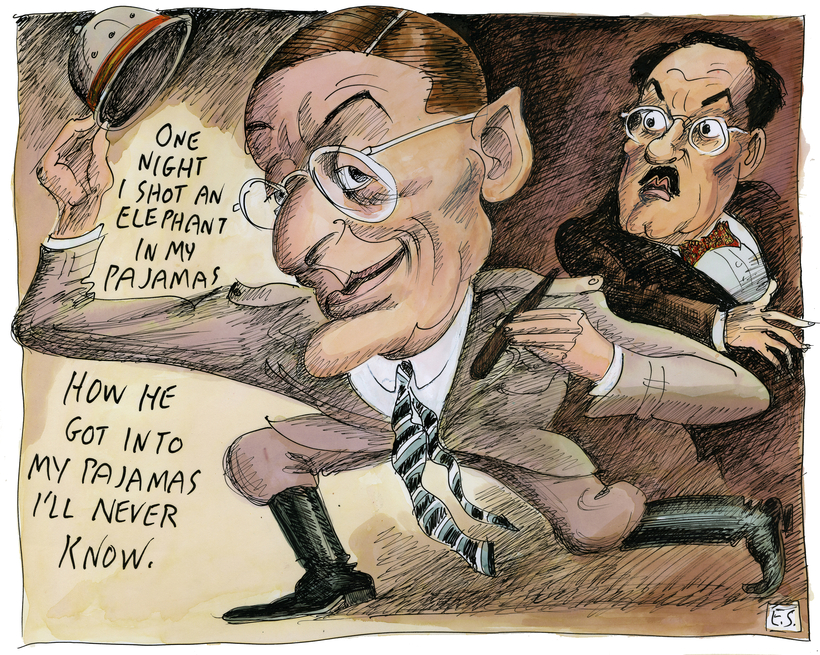

Groucho Marx, like many great comics, was feeling melancholy, contemplating his Marx Brothers–less future. Across the ocean, like many great poets, T. S. Eliot was thinking about the past—his St. Louis childhood, the movies, and music halls he had loved as a younger man.

By the beginning of the 1960s, T. S. Eliot was not just the most renowned poet alive but was widely regarded as the finest English-language poet of the 20th century. Groucho, however, was somewhat at sea after a run as one of America’s favorite comedic actors whose movies had entered the bloodstream. His game show, You Bet Your Life, had just ended. He was considered for the host of The Tonight Show, but instead the reins were passed to a young game-show host named Johnny Carson.