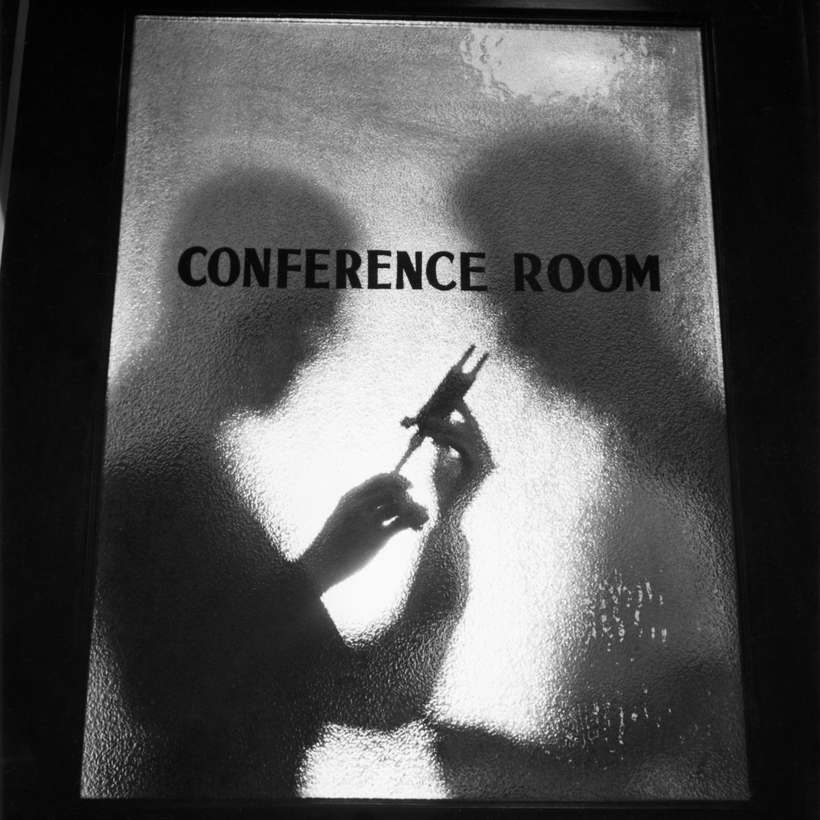

On the eve of the coronavirus-vaccine rollout, an ethically compromised subset of 1-percenters are already scheming about ways to cut the line.

If you are a certain type of person, there are ways to justify almost anything, including stepping ahead of the heroic health-care workers, to get the vaccine. As one well-connected woman put it, “It’s hardly like a middle-aged man jumping on a Titanic raft before a woman and her children. This isn’t life or death.” Well, maybe not for everybody.