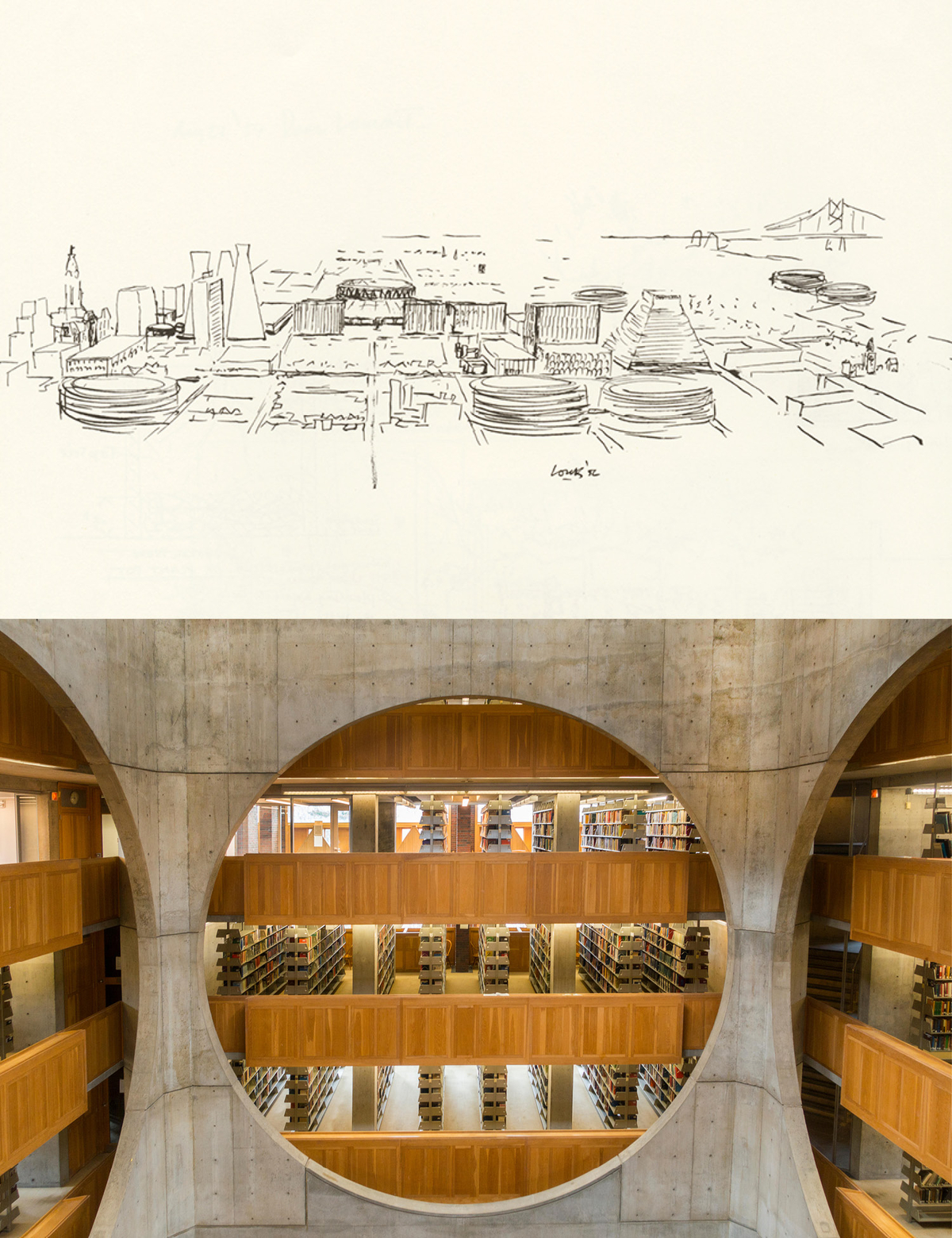

“If architecture can be expressed as a world within a world, then this building expresses it well,” wrote the architect Louis Kahn in his 1962 monograph, The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn. The building he was referring to was Rome’s Pantheon, but the line is telling of the book as a whole. Originally published by Richard Saul Wurman, at the time Kahn’s 25-year-old employee and former student, and Wurman’s partner, Eugene Feldman, it offers a window into the mind of the 20th-century architect behind such epic buildings as Fort Worth’s Kimbell Art Museum, La Jolla’s Salk Institute, and the Yale University Art Gallery, in New Haven.

Born in Russia, Kahn immigrated to the U.S. with his family when he was young. By the time Wurman and Feldman approached him about doing a monograph, he was 59 and well into his distinctive style of stark, sturdy geometric forms in brick and concrete. Split into two sections—early sketches and renderings, and sketches produced during Kahn’s European travels—and interspersed with text by Kahn, the monograph gives insight into his design approach, but also into his approach to life generally. “To an architect the whole world exists in his realm of architecture,” he writes in the foreword. “When he passes a tree he does not see it as a botanist but relates it to his realm.”