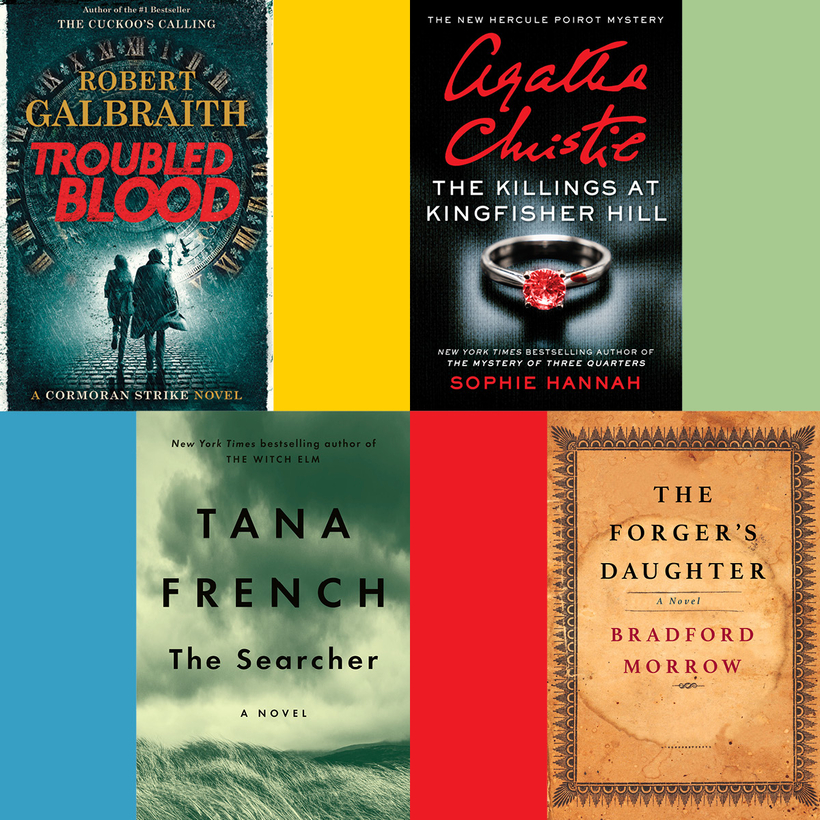

It’s remarkable how convincingly, under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith, J. K. Rowling has taken command of another genre. Troubled Blood is her fifth and, at 900-plus pages, most ambitious—and now controversial—Cormoran Strike novel. Strike, an Iraq-war veteran and amputee with the imposing bulk of an ex-boxer and a rock-star father he’s met only twice, runs a London-based detective agency with his young partner, Robin Ellacott. Thanks to some high-profile successes, the agency is thriving when they’re asked to take on a cold case from 1974—a doctor who left work one evening and disappeared without a trace. There was speculation at the time that she had fallen victim to a local serial killer, but her daughter wants definitive proof of her fate and Strike agrees to try. Besides the serial killer, the doctor’s medical practice, friends, and family present a diverse tapestry of suspects and possible motives. Strike and Robin need every minute of the year they’ve got to work the case.

The police detective originally assigned to the crime was let go after going down a freaky rabbit hole involving astrology and the tarot, but his theories are worth a second look. Then there’s Strike’s knotty personal life, most urgently his need to attend to the cancer-stricken aunt who raised him, and, simmering in the background, his nuanced relationship with Robin, whose traumatic history and professionalism make her wary of involvement. The long-running thread of sexual tension between these two appealing but damaged characters exerts an irresistible pull equal to that of the mystery.

I will leave it to the reader to ponder whether the serial killer, a man who dressed in drag to signal his harmlessness to potential victims and appears mainly as a background presence, embodies what Rowling’s detractors describe as her transphobia. Though not all of this sprawling novel ties in with the conclusion, Rowling remains a spellbinding storyteller, and you won’t regret going down the alternately harrowing and amusing byroads to reach the emotionally rewarding conclusion.

If the title of Tana French’s latest novel is a nod to John Ford’s classic Western The Searchers, the similarity stops there. Former Chicago cop Cal Hooper isn’t much like John Wayne’s vengeful obsessive, but rather he is French’s updated ideal of the disillusioned lone cowboy, this one looking for peace of mind in rural Ireland.

Though described as a backwoods boy from North Carolina, Hooper feels more like an archetype than this origin story suggests. Smarting from a divorce and no longer confident on the streets, he’s moved to a tiny, remote village, where he’s bought a house he found on the Internet. Hooper wants only to sink into the quiet, enjoy the wild beauty of the place, and work on his tumbledown house, but inbred Irish towns being what they are, his neighbors want to get in his business, give him advice, and set him up with eligible women. Despite his polite detachment from most of this meddling, Hooper is unable to ignore a tortured plea for help from a tough but skittish kid from one of the worst local families, whose older brother disappeared six months earlier. After much pub- and shop-going, wallpaper-stripping, furniture-sanding, and teenager-whispering, Hooper finally cranks up the search for the missing Brendan Reddy, and once he does, wishes he’d left well enough alone.

Die-hard Tana French fans will appreciate her beautifully written burrow into the culture of Irish villages and exhaustive exploration of the contours of a decent, honorable man’s mind, but with a plot that seems too slender to hang such a substantial book on, The Searcher may be slow going for others. And the revelations about Reddy and the town, when they do come, are not forehead smackers; French has painted the picture so completely that they seem inevitable.

Sophie Hannah’s fourth entry in her well-received, authorized reboot of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot series begins promisingly. She does a wicked Poirot, not slavishly identical to Christie’s but sharply drawn and delightfully brusque. Poirot and his sidekick, the not-as-swift Inspector Catchpool of Scotland Yard, are traveling by passenger coach to a private country estate called Kingfisher Hill at the behest of one Richard Devonport. His fiancée has confessed to the murder of his brother, and Devonport has asked Poirot to exonerate the woman, who’s been sentenced to death. During the journey the two detectives have unsettling encounters with two separate women, one inexplicably terrified and the other “rebarbative” (great word, meaning repellent) but possessed of such marble-like beauty that Poirot privately nicknames her “the Sculpture.” Seated next to Poirot on the bus, the Sculpture proceeds to have a shocking and unpleasant conversation with the detective.

When Poirot and Catchpool arrive at the Devonport-family mansion, using a cover story at the request of their client, they encounter none other than the Sculpture, who turns out to be the sister of Richard and the murdered man. Here the story gets effortful and unnecessarily complicated. Between guests and family, there’s a houseful of suspects, some of whom resemble collections of psychological tics rather than actual people. Hannah’s own novels usually go deeper than this; channeling another writer surely has its limits. The solution to the murders—another unsurprising one occurs farther along—turns out to be believably human, but a bit unsatisfying for the reader. It is disappointing that the handsome, charismatic brother was pushed off a balcony before we could meet him. He might have been a nice offset to the other characters, most of whom are, it’s fair to say, rebarbative.

If you believe that forgery, specifically in the art and rare-book worlds, is a nonviolent, victimless sort of crime, The Forger’s Daughter will give you pause. The consequences of this shady occupation resulted in a fair amount of bloodletting in this novel’s predecessor, The Forgers (2014), leaving its protagonist, Will, with a maimed hand (courtesy of his nemesis and fellow forger, Henry Slader) and his girlfriend Meghan’s brother brutally murdered. The discreet mayhem continues in this sequel.

Morrow picks up the story 20 years later with the return of the sinister Slader, recently released from prison. Will, a convicted forger of famous authors’ signatures, has since gone straight, settling down quietly with Meghan, now his wife, and their two daughters. Slader first makes his presence known by spooking Meghan and their younger daughter near their farmhouse in the Hudson Valley, then steps out into the light to propose a deal: he wants Will, who has added letterpress printing to his skills, to copy an ultra-valuable edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Tamerlane” that he has “acquired” from a personal collection in order to switch out the fake and sell the authentic one. Though he’s sworn not to return to his old ways, Will harbors a terrible secret that Slader has discovered, so he must comply or be ruined. But the blackmailer doesn’t realize how far he’s pushed the envelope with his demand that Will involve his talented older daughter in the project. The contrast between the refined rare-book world and the viciousness it engenders keeps you off-balance, as do Will’s slippery narration (shared, to no great effect, with Meghan) and the stilted, sometimes florid language that doesn’t jibe with the contemporary setting. Nearly every character in this novel is practiced at the art of deception, so reader beware.

Lisa Henricksson reviews mystery books for AIR MAIL. She lives in New York City