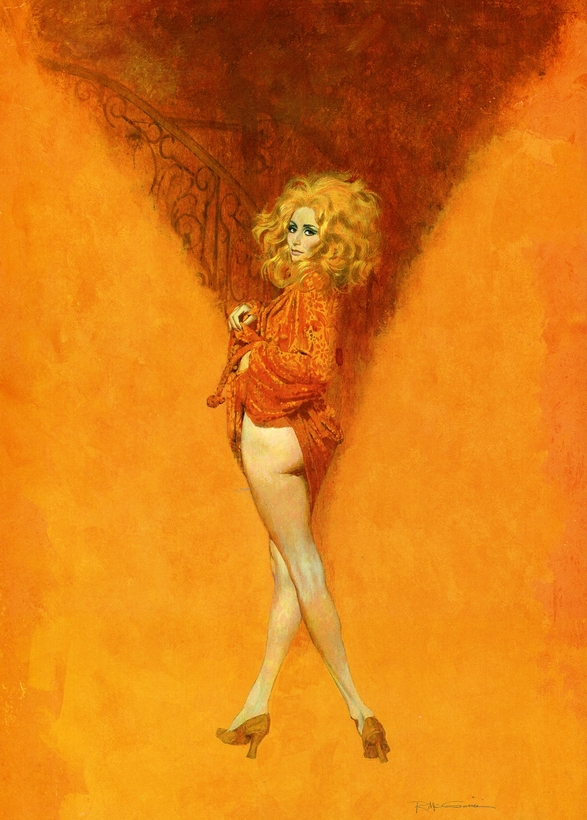

As with all Robert McGinnis models, she was stunning: the flaming red-orange hair, flaring out like Medusa’s; the flawless parchment-white skin, fit for a Brontë heroine; the smoldering, beckoning eyes. She was fiercely cerebral and had a marvelously dry wit, and both showed in her face. She was one of the last women who knew how to smoke glamorously.

Shere Hite would go on to win international fame as an authority on female sexuality. But in the 1960s she was merely a boho Ph.D. student living in a cramped Manhattan basement apartment, modeling to pay the rent. In contrast, by the mid–20th century Robert McGinnis was at the top of his game and one of the nation’s leading illustrators: his galér of lithe, leggy sirens, ripely sexualized and barely dressed, adorned countless dime-store crime novels and movie posters. Hite posed for many artists, but she was McGinnis’s muse. She died last month, at the age of 77.

“She was very bright, and she had great fashion savvy,” recalls McGinnis, who at 94 is still illustrating from his Connecticut studio. “She could produce a great range of moods on her face. She had this beautiful snow-white complexion, and she knew how to move her body, to show it off to its best effect. You can’t teach that; it has to be intuited. Other models didn’t have her intelligence.”

In 1976, Hite published The Hite Report, a groundbreaking best-seller that upended decades of accepted Freudian ideas about what women wanted in bed. As her identity as a global sexologist and provocative talk-show guest blossomed, her pulp-fiction illustrations, painted by McGinnis, receded into the background. Look at them today and you see far more than a spicier version of Tina Louise. You can almost feel Hite’s feminine ferocity fulminating from the canvas.

She was stunning: the flaming red-orange hair, flaring out like Medusa’s; the flawless parchment-white skin, fit for a Brontë heroine; the smoldering, beckoning eyes.

On the cover of The Creative Murders, she’s a contemptuous dominatrix in purple pasties and panties, holding aloft a massive ostrich-feather boa; on The Unorthodox Corpse, she’s an alabaster vision, seductively beckoning over her shoulder; on Always Leave ’Em Dying, she’s lounging provocatively on a fluffy white rug, nude except for a pair of strapped red pumps, daring your desire. In the stunning pastiche McGinnis painted for Judith Krantz’s saucy 1980 potboiler, Princess Daisy, Hite is all creamy skin and platinum hair, serene, knowing, enigmatic. Her portraits share one trait, and that is that they are utterly compelling. You can’t look away.

Their process was simple. McGinnis would recite the plot of a book being illustrated, and Hite would dig up jewelry or scarves, or often nothing, to pose in to capture the story’s standard, dark, carnal vibe.

While Hite embodied the archetypal sensuality of the McGinnis Woman, she also transcended it. Born in Missouri, she possessed an icy beauty that exuded a kind of weary European sensibility. If other femmes fatales in the McGinnis canon were gangster and gumshoe molls in the vein of Veronica Lake, Hite was the Russian nobleman’s bored wife, languishing in the castle and waiting to be ravished—a more Dionysian, earthy Anna Karenina.

A few years after Hite’s book catapulted her to fame, McGinnis found himself in a swanky residential building off of Central Park and, glancing at the tenant directory in the lobby, noticed SHERE HITE listed. She was soon taking him on a tour of her grand apartment, where her husband, the German concert pianist Friedrich Höricke—20 years her junior—played in an oak-paneled drawing room with a huge fireplace and twinkling chandeliers. “It was,” McGinnis says, “the most elegant room I’d ever been in.” It was the last time he saw his beguiling afflatus.

“Women want two things,” he says. “One, they want to be beautiful. The other is they want to be seen. They’re always aware if somebody is watching them. Shere was. She enjoyed it. She wanted to be seen.”

Michael Callahan is a Philadelphia-based writer