The impassioned debate over The New York Times’s 1619 Project may seem like it’s about race, but it’s also about the race to replace the paper’s executive editor, Dean Baquet. And here’s the odd part: the lead contenders competing to follow the only Black man to have ever held the top job are all white, middle-aged, straight men.

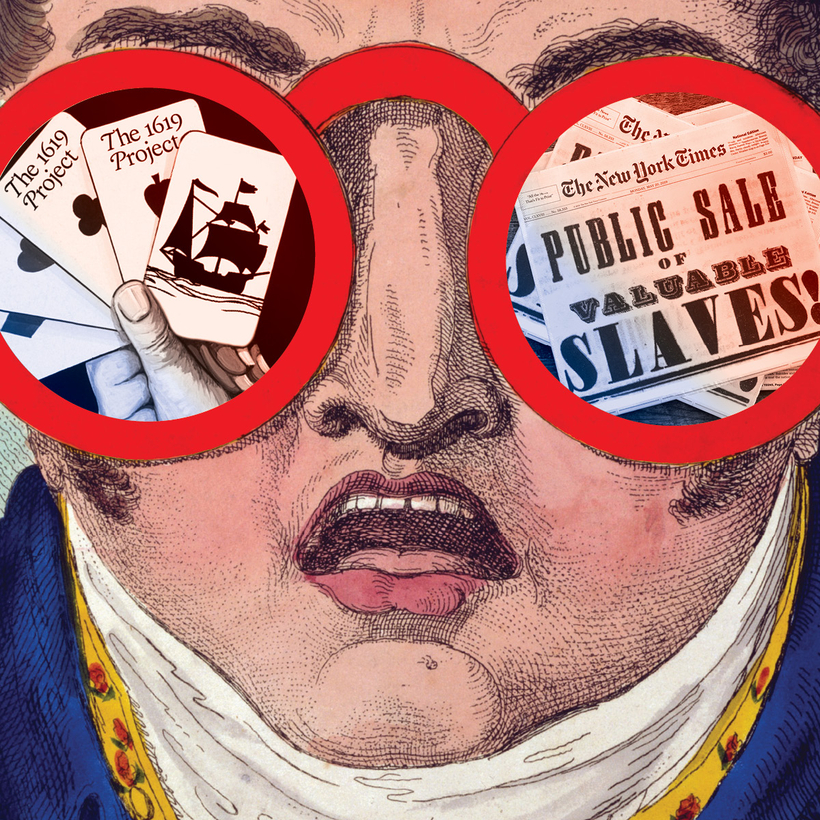

Let’s go back to the beginning. Last year, The New York Times Magazine published a multi-media issue, overseen by Nikole Hannah-Jones, in which she made the bold claim that the American Revolution was fought not for independence but to preserve slavery. She posited that America’s true founding was not July 4, 1776, but 1619—the year the first slave ship arrived off the Virginia coast.

It won a Pulitzer. It is taught in schools. And then the second-guessing bubbled over. Prominent historians disputed the premise, and some facts. Donald Trump accused the Times of “toxic propaganda” and “ideological poison.” Or, as Sarah Ellison explained in a thoughtful, Rashomon-style account of the meltdown in The Washington Post this week, “it is the subject of dueling academic screeds, Fox News segments, publishers’ bidding wars and an upcoming series of Oprah-produced films. It is a Trump rally riff that reliably triggers an electric round of jeers.” After the N.Y.U. journalism school gave the 1619 Project a new honor, Hannah-Jones on Wednesday tweeted how welcome the recognition was, “this week of all weeks.”

Here’s the odd part: the lead contenders competing to follow the only Black man to have ever held the top job are all white, middle-aged, straight men.

And within The New York Times, the 1619 Project unleashed a frenzy of debate, self-flagellation, and finger-pointing—and, most lately, a torturously civil smackdown by Bret Stephens, a conservative columnist at war with the wokerati. Stephens attacked the magazine’s editor, Jake Silverstein (more on him in a minute), writing that Silverstein, ignoring Times protocol, surreptitiously “disappeared” the project’s claim about the year 1619 being America’s “true founding.” He also cut one of the most contentious lines, the claim that in 1619 “America was not yet America, but this was the moment it began.”

Think about it: it’s 2020, and while diversity is well represented in the pages of the paper, it is in short supply at the upper ranks. Unlike Baquet, who turns 65 next year, the top editors with their hands up—and elbows out—are not just white; most have Ivy League degrees, or family money, or connections and other advantages that used to provide a leg up for ambitious journalists and that are decidedly uncool in the current era.

Among the front-runners: Joe Kahn (Harvard), 56, the managing editor, was a Beijing correspondent and won two Pulitzers; associate managing editor Cliff Levy (Princeton), 53, is a former Moscow bureau chief and Metro editor, and also won two Pulitzers; Sam Sifton (Harvard), 54, is the former restaurant critic who developed the Cooking app. Dark horses include magazine editor Jake Silverstein (Wesleyan), 45, who edited Texas Monthly, and Sam Dolnick (Columbia), 40, an assistant managing editor who helped develop The Daily and is a fifth-generation Sulzberger.

So, the front-runners had to … make adjustments. Particularly because The New York Times’s publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, 40, has made racial diversity and cultural sensitivity his cause, much the way in the early 1990s his father, A. O. Sulzberger Jr., broke with the paper’s antediluvian biases to champion gays and women. (Full disclosure: I was a beneficiary of that recruitment drive, and until I left the paper, in 2017, had a partially obscured mezzanine view of these leadership tryouts.)

The New York Times’s publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, 40, has made racial diversity and cultural sensitivity his cause.

So, at a moment when even Joe Biden is boasting that, if elected, he will be the first non–Ivy League president in ages (actually, since Ronald Reagan), what on earth is a talented, ambitious, and seasoned editor whose bio is out of sync with the reigning newsroom ethos—and the publisher’s own mission statement—supposed to do to advance? Or even survive?

One way is to cast yourself not as a relic of the ruling class but as a digitally savvy, business-minded innovator with a vision for new platforms, including podcasts, streaming, and “narrative journalism.” Another is to position yourself as the paper’s most aggressive, vocal advocate for diversity, social justice, and economic equality. Some are more righteous than others. Behind his back, reporters refer to The New York Times Magazine’s editor as “Woke Silverstein.”

They are moves that can backfire. Take James Bennet, 54 (Yale), until recently the editor of the op-ed page and a leading contender for the top job. Bennet tried to be both digitally savvy and politically progressive, but after he ran (he said he didn’t read it) a repugnant “send in the troops” column by Republican senator Tom Cotton in June at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests, all hell broke loose in the newsroom. Sulzberger stepped in to say the piece should not have run, but the staff continued to fulminate and nobody came to Bennet’s defense, especially not his rivals. He had to resign.

Behind his back, reporters refer to The New York Times Magazine’s editor as “Woke Silverstein.”

This week, after Bret Stephens’s column on Sunday sent Twitter, internal Slack channels, and even the Times’s union into orbit, Sulzberger defended the columnist’s right to voice his objections, however objectionable his objections might be. But he dismissed all criticism and called the 1619 Project a “journalistic triumph” and “one of the proudest accomplishments of my tenure as publisher.” That endorsement evidently didn’t assuage staffers enough, because, on Tuesday, Baquet chimed in with the exact same message, assuring the newsroom—and the world—that all the criticism of the piece is unfounded and that “1619 is one of the most important pieces of journalism The Times has produced under my tenure as executive editor.”

The internal struggles at The New York Times can be baffling and contradictory, but they are habitual, highly public, and agonizingly self-serious. And they often are sparked by seemingly stupid oversights—not just publishing something that you didn’t read but also publishing something that may be based on fiction or a lie or both. In the most egregious cases, the cause isn’t carelessness; it’s usually people caring too much about their own careers.

This week, the paper’s excellent media columnist, Ben Smith, wrote in depth about the holes in the newspaper’s podcast Caliphate, a gripping tale about ISIS fighters in Iraq. Smith deconstructed the reporting of Rukmini Callimachi, a foreign-desk supernova favored by some editors and mistrusted by many of her peers, and concluded that almost the entire exercise in “narrative journalism” was based on one source, a Canadian-born Isis member who could not be found, not even by Callimachi, and may not exist at all. Canadian police last month arrested an alleged con man who appears to have used the source’s name as an alias. (This stuff happens. Let us not forget Judy Miller’s reporting on W.M.D. in Iraq and the completely false news stories made up by Jayson Blair.)

Smith framed the underlying problem of Caliphate-gate as a struggle between old-school journalists with a buzzkill insistence on fact-checking, paper trails, and multiple sourcing, and those who want to gussy up the platform with, as Smith put it, a “juicy collection of great narratives, on the web and streaming services.” These are the editors who want every story to have the “heat” of the podcast Serial. (Not surprisingly, The New York Times this summer bought the production company that produces Serial.)

In the most egregious cases, the cause isn’t carelessness; it’s usually people caring too much about their own careers.

As he delineated how the people in charge brushed aside the concerns of editors and reporters to showcase Callimachi, Smith rather bravely named names, including Joe Kahn, the paper’s managing editor, who a year ago seemed like a shoo-in to succeed Baquet, and another newsroom hotshot, Sam Dolnick, the publisher’s cousin, who, among other tasks, oversees audio.

If these two latest wounds to the paper’s reputation are even partly rooted in insecurity and rivalry, you have to wonder why Sulzberger doesn’t look beyond the circle of white, middle-aged Yale men in Brooks Brothers shirts and find people more naturally in step with his mandate and the newsroom’s Zeitgeist. The answer is: it’s not that easy.

The Times is still a great newspaper, and possibly the most respected in the world. But the dirty little secret of modern journalism is that the best and the brightest don’t necessarily want to be in charge of the newspaper of record, let alone second or third in command.

Being the executive editor of The New York Times is not fun. These days, it’s more akin to being the commander of a Nimitz-class nuclear aircraft carrier—prestige and power, sure, but at the cost of huge stress, relatively low pay, little room for error, lots of second-guessing in Washington, and buckets of blame when something goes wrong. At sea, the glamour and glory go to the fighter pilots; in a newsroom, the top guns are writers and columnists with marquee bylines, huge social-media followings, book contracts, and pirouettes on cable news.

Being the executive editor of The New York Times is not fun. These days, it’s more akin to being the commander of a Nimitz-class nuclear aircraft carrier.

Many of the most talented New York Times journalists are female, Black, Hispanic, Asian, gay, or young, with all kinds of new media opportunities outside the paper. I think one reason so few prominent women there seem to be angling for the top editing jobs (assistant managing editor Carolyn Ryan is one, maybe) is because the leading lights don’t want or need to be in management. Hannah-Jones is a superstar, but she wants to write, not go to budget meetings. (Though there are rumors she might take over the op-ed pages.)

When I was there, management had high hopes for Lydia Polgreen, an ace foreign correspondent and experienced editor who is also female, Black, and gay. Polgreen left the Times in 2016 to become the editor in chief of the Huffington Post and is now head of content at Gimlet Media. There are still plenty of promising younger candidates in the talent pool, but how many of them will wait their turn if they have exciting options elsewhere?

Call it Karma, but this isn’t as good a time for white men in their 40s and 50s to seek rewarding jobs in journalism. So after putting in decades of hard, commendable work at the paper, a senior-management role at the Times—like a board position at the Racquet & Tennis Club on Park Avenue—is a refuge that confers stature and authority.

It’s not always nice work, but at least they can get it. Or one of them can. The rest may be set adrift by the rip currents of history.